Question: Is it a good idea to buy a company at its IPO? I've heard it's better to wait until the price settles down a bit.

Answer: As you allude to in your question, the oft-cited advice is to let the stock price "settle" after an initial public offering before taking the plunge; institutional investors' trading activity can cause an IPO stock to soar on its first day of trading, but this inflated price might not be sustainable.

Jay Ritter, a professor of finance at the University of Florida, looked at data from over 8,000 IPOs from 1980 to 2015 and found that the mean return of an IPO on its first day of trading is 18%. However, as Ritter's data again concludes, the three-year buy-and-hold returns of IPOs (assuming you bought an IPO on the first day and held it for three years) generally underperform the market, and are particularly poor for companies that have less than US$100 million in annual revenues. This lends credence to the conventional wisdom that buying IPOs on the first day of trading may not be a profitable strategy.

But while it's wise to be aware of these trends, no two companies (and hence no two IPOs) are exactly alike. It pays to take a more nuanced approach to looking at valuation. The best way to avoid overpaying for shares of a hot new IPO is to come up with your own fair value estimate of the company's shares, and not pay more than that. (I know--easier said than done. The examples below can help illuminate.)

Let's take a closer look at how IPOs' initial prices are determined and some of the forces that shape those prices in the market. Then we'll take a closer look at how Morningstar analysts think about a company's intrinsic value, and we'll see whether we would have been buyers of four prominent IPOs on their first day of trading.

How IPO pricing works

Have you ever noticed that after a company's initial IPO price is announced, that initial price might not even come into play at all on the first day of trading? Often the stock opens higher than its initial pricing range. This has to do with how the IPO process works.

A company looking to go public will usually hire an underwriter (or underwriters) such as a large investment bank to help facilitate the process of selling its shares. The underwriter will talk to its clients (institutional investors, mutual funds, pension funds, hedge funds and the like) to gauge interest in the firm and to set an offering price. Once the price is set, those same institutional clients are the ones that get dibs on the shares at the IPO price.

By the time the shares start trading in the open market (in other words, when smaller individual investors have access to them) the part of the company that was sold off is already in the hands of those sophisticated investors. This means the share price is determined by the normal supply and demand of the stock market, not what the underwriter and the firm set as the initial price.

What's your fair value estimate?

At Morningstar, we use a discounted cash flow model to come up with a fair value estimate range. Essentially, that means that we think a firm's intrinsic worth, or fair value estimate, is equal to the value of the cash the business can generate in the future. But the cash that is generated today is worth more to investors than the cash that could be generated in the future due to the uncertainty that the business will actually deliver those results. And if you give up a dollar today to buy that future cash flow, you have the opportunity costs of using that dollar to invest in other, potentially safer assets. For this reason, we apply a discount rate to those future cash flows to account for these unknowns.

Our estimate of fair value is independent of where the shares are trading in the market, so we value shares of an IPO the same way we value shares of a company that has been trading for years. We think a stock is an attractive buying opportunity when it is trading at a discount to our fair value estimate. In the case of U.S.-listed companies, an analysis of the information found in the S-1 -- a detailed registration statement that the underwriter(s) file with the Securities and Exchange Commission prior to the initial public offering -- is crucial to coming up with a fair value estimate for an IPO. (Here is Snap's S-1, for example.)

Four IPOs: Would we have been buyers?

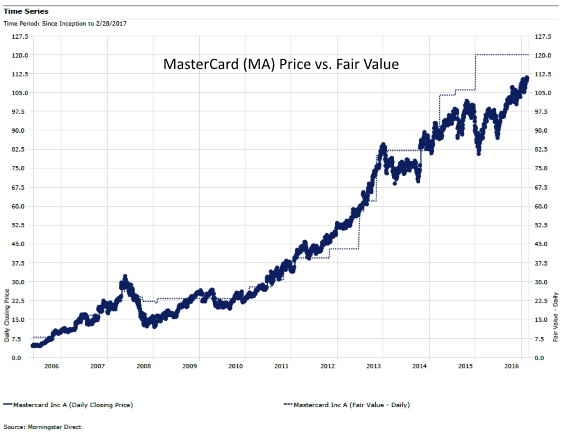

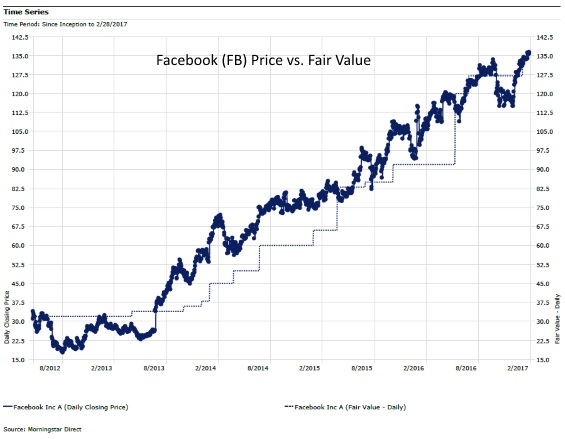

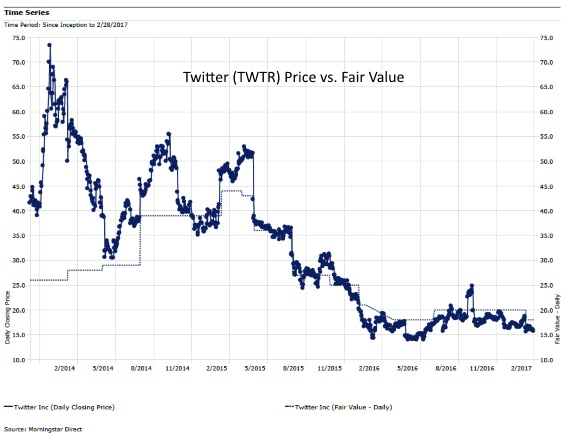

Let's take a look at a few IPOs and see whether we would have been buyers on the first day of trading based on our fair value estimate. (In the charts below, the thicker solid line is the stock's daily closing price and the thin, dotted line is its Morningstar fair value estimate. All figures are in U.S. dollars.)

![]() MasterCard (MA)

MasterCard (MA)

Initial Public Offering: May 25, 2006

Priced at: $39

Opened at: $40.30

Closed at $46

Debut session gain: 18%

10-Year Return (Annualized): 27.2%

This is one we would have scooped up at the IPO. At the time of MasterCard's initial public offering of around $40 on May 25, 2006, we thought each share was worth twice that amount. We estimated that the IPO price represented a 0.49 price/fair value ratio (our fair value for MasterCard was $80 per share).

Our thesis then was that MasterCard was well positioned to benefit from the powerful trend in the global payments industry of moving away from cash and checks (which had historically dominated) and toward electronic forms of payment. We initiated coverage of the company with a wide moat and it retains its wide moat rating today.

(Note: This price data is split-adjusted for a 10:1 split in January 2014.)

![]() Facebook (FB)

Facebook (FB)

Initial public offering: May 18, 2012

Priced at: $38

Opened at: $42

Closed at $38.23

Debut session gain: 0.6%

3-Year Return (Annualized): 26.72%

Upon Facebook's initial public offering at $38 per share on May 18, 2012, we thought the price was overly optimistic. We valued the social network at $32 per share; our P/FV at the IPO was 1.18.

And for much of 2012, the stock was trading below its IPO price. In hindsight, waiting for the dust to settle for a few months after Facebook's IPO (which had a number of bumps in the road, including a last-minute change in the initial number of shares to be sold) would have been the wiser move. The low of around $18 in September 2012 would have been a great entry point. Of course, hindsight is 20/20, but as you can see from the price/fair value chart below, we felt that the stock was trading at a compelling valuation at that time.

We have always maintained that Facebook has a wide moat rating based on network effects around its massive user base and intangible assets consisting of a vast collection of data that users have shared on its various sites and apps. We steadily increased our fair value estimate over the past few years as we saw increasing evidence that Facebook has been able to leverage its large audience and valuable data into online advertising revenue.

![]() Twitter (TWTR)

Twitter (TWTR)

Initial public offering: Nov. 8, 2013

Priced at: $26

Opened at: $45.10

Closed at $44.90

Debut session gain: 72.6%

3-Year Return (Annualized): -34.5%

When Twitter's initial public offering took place, we thought it was fairly valued; we initiated coverage of Twitter at $26 per share on Nov. 8, 2013. After the price soared nearly 73% in its first day of trading, it was well out of our buy range, however.

As our price/fair value chart indicates, we have become less optimistic about Twitter's prospects over time (as has the market). We recently downgraded our moat rating on the firm from narrow to none; slowing user growth is dimming Twitter's competitive advantages in our opinion. We see the company as fairly valued today relative to our $17 fair value estimate.

![]() Snap (SNAP)

Snap (SNAP)

Initial public offering: March 3, 2017

Priced at: $17

Opened at: $24

Closed at $24.48

Debut session gain: 44%

We would take a pass on the shares of Snap at the current price. Our fair value estimate is $15, resulting in a current price/fair value of 1.4 (as of March 13). We think Snap and its users benefit from a network effect among its customer base and is starting to attract the attention (and dollars) of advertisers with a growth trajectory toward $1 billion in revenue. But equity analyst Ali Mogharabi points out that there is no guarantee that Snap will effectively monetize these users on a consistent basis, and we aren't convinced about the firm's ability to generate excess returns on capital over the next decade.