Markets continued on a roll this week, extending their weekly winning streak to four. Equity markets around the world were generally up 1% to 2% this week. The weekly gain almost got the S&P 500 back to the flat line for the year.

With corporate earnings season winding down and almost no U.S. economic news, the focus was on a broad range of new monetary stimulus actions by the European Central Bank. Those actions were far stronger than expected and included a multifaceted attack on slow growth and low inflation. However, the report came with one surprise that the market did not initially like. Namely, ECB President Mario Draghi said this may be the end of the line for even more negative rates. In the ECB's opinion, more negative rates would potentially harm banking system profits. These stingy-sounding statements quickly ended the markets' cheery reaction to the new stimulus.

However, as we point out later, announcing a potential end to ever-low rates has the potential to force some reluctant borrowers off the sidelines. This line of logic apparently sank in on Friday as markets soared after Thursday's confused response. The positive response was not limited to Europe as money again proves to be the ultimate fungible commodity, easily leaking from one market to another. Commodities also did well with the new monetary stimulus gaining over 2% on the week. Despite the ECB move, U.S. interest rates moved modestly higher from 1.88% to 1.98% for no particular reason.

Because there was almost no economic news this week, we are focusing on the NFIB Small Business report. While the short-term readings of the report can be hard to interpret, longer-term trends are clear. Small-business prospects are not what they used to be, and some of those worries may spread to larger corporations over the next several years. A toxic combination of slow growth, limited ability to raise prices and ongoing wage pressures have put small-business profit growth on hold and put business owners in a sour mood.

Is ongoing weakness in small-business confidence the early warning?

Small businesses have been growing generally more pessimistic for years, not just in this month's report. Some of the things that are making small businesses nervous have the potential to spread more broadly across the economy. For that reason we are highlighting the report this week despite some reservations about the meaningfulness of the short-term results, proper seasonal adjustments and varying monthly sample sizes. Before tackling the more valuable longer-term implications of the report, let's take a quick look at the February data.

The monthly survey of small-business owners showed some deterioration in headline numbers, and even some of the more useful employment sections of the report showed month-to-month declines. We always worry that this survey isn't terribly forward-looking, but this month our concerns were even greater as the recent reports appear to have a backward-looking bias. The index actually went up in December when markets and oil prices began a renewed leg down, perhaps reflecting better results in earlier months. Then business sentiment declined sharply in January as market conditions worsened and relatively bad economic news for December was reported in January. There was further deterioration in February, even as markets and the economy looked a lot better in the most recently reported sets of economic news.

At just 92.9, the report is at its lowest level since February 2014 (probably not a coincidence, but the data is supposed to be seasonally adjusted). We suspect a few things. First, some of the crummy economic data in December was a statistical mirage, as was the rebound in January and February. Just maybe, small-business owners figured that out, looking at their own business results.

Second, scary headlines tend to move a lot of sentiment surveys, including both consumer surveys, this small-business survey, and more recently, even purchasing manager data. February headlines were not exactly filled with joy. Finally, small businesses continue to face a number of longer-term headwinds that continue to pressure the index in good times and bad. The index was originally set to 100 for average, normal times. More recently it has averaged just 96. The picture below says it better than we can.

Many different pressures are at work here. Many more typical small businesses have consolidated into a small number of big-box companies, including bookstores, office supply stores, sporting goods stores and electronics and appliance stores. Or worse yet, they face online competition. Also, tax and regulatory burdens have grown over the years, and it is generally easier for larger companies to deal with those challenges. Even seemingly wonderful initiatives, such as extended parental leave, are far easier to adopt in large corporations with a bigger base of labour than a small automotive repair shop with a handful of employees.

Longer-term small-business trends do not bode well for corporate profits across the economy

But what has really caught our attention is the pressure that small-business owners are facing with regard to profitability. We imagine this is what really has gotten business owners down.

The most recent report suggests that it is increasingly hard to raise prices at the same time as they are forced to pay workers more--that is, when they can even find the workers. For three months in a row, the number of businesses forced to implement price decreases has exceeded those that have raised them. Meanwhile, though dipping in February, the net percentage of firms increasing actual wages has remained in the low to mid-20s despite their best intentions to keep a lid on wage growth in the future.

Sales aren't growing much. In a world of demographically challenged growth rates, higher wages and limited potential to raise prices, profit growth potential is a challenge, to put it mildly. These trends have been burning for more than a year in the small-business segment. We have some fears that these same pressures while eventually catch up with midsize and large businesses. Small businesses just happen to be the most vulnerable, and they may just be the canary in the coal mine of ongoing profit issues across the broader economy.

European Central Bank offers more stimulus in effort to fight low inflation (by Roland Czerniawski)

On Thursday, ECB President Mario Draghi announced a series of new measures aimed at stimulating the European economy and attempting to end to the lingering issue of low inflation. In a nutshell, the ECB did the following:

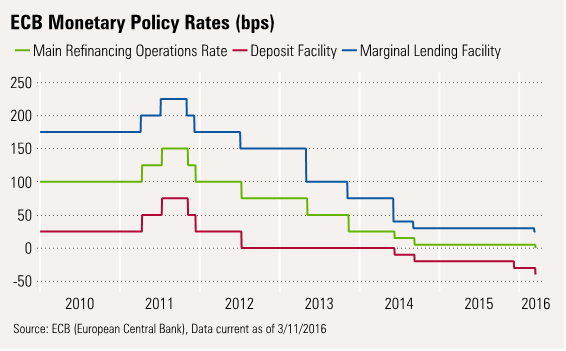

- Cut three main policy rates. The deposit facility (interest that banks receive for their excess funds deposited with the ECB) was lowered to negative 0.4% from negative 0.3%. Additionally, the marginal lending facility (the rate that the ECB charges qualifying banks for overnight loans) was cut to 0.25% from 0.30%. Finally, the main refinancing operations rate (the rate that the ECB charges banks for collateralized loans structured similarly to repurchase agreements) was cut to zero from 0.05%.

- Announced the expansion of its current quantitative easing program from 60 billion euros per month to 80 billion euros per month.

- For the first time, included investment-grade corporate debt as part of the asset purchases.

- Announced a new series of four targeted longer-term refinancing operations. Those funds are meant to provide longer-term liquidity to the banking system.

- Draghi underlined that further cuts most likely won't be necessary.

The announcement of more stimulus measures was widely anticipated, but very few expected that Draghi would increase the QE by as much as 20 billion euros and expand asset purchases to include corporate bonds. We view these changes as surprisingly stimulative with a certain measure of shock and awe (similar to the surprise element of Bank of Japan's negative rates program in January). The shock and awe (which has become almost an expected part of Central Bank announcements around the world) worked for several hours, as the euro and European stocks surged. Then Draghi seemingly undid all the good when he strongly implied this was it, the end of the line for more rate cuts. He implied the ECB did have more monetary ammunition, but that banking industry profit issues meant that even more negative rates would not be the most likely line of attack.

Overall, the new monetary package is meant to spur more lending and fight the low-inflation environment that has been tormenting the European economy for years. Draghi's commitment to no more cuts certainly brought some unpredictable results immediately following the announcement. However, we believe that the no-more-cuts policy could provide incentives to borrow, in addition to the incentives to lend engendered in a negative rate policy for banks.

In a deflationary spiral it is well known that consumers postpone their purchases in anticipation of lower prices. The same is likely true with regards to borrowers postponing taking out new loans in anticipation of even lower rates. Even the threat of stable rates just might be enough to get fence-sitting borrowers to jump off. (We saw a version of that in the U.S. in 2013 when the Fed threatened to ease bond purchases, sending mortgage rates modestly higher and temporarily causing homebuying to surge as buyers rushed in to lock in low rates.) At this point, Draghi had to make it clear that this is likely going to be the cheapest money available for years to come, hoping that borrowers jump on the opportunity.

The logic of putting a quasi-end to ever-falling rates appears sound. It seems to be an interesting new tool, this time on the demand side, to get lending moving again. After the negative rate policy was implemented in June 2014, lending did jump, as shown below, with the blue lending line jumping just as interest rates (the red line) crossed below zero. However, that recent "surge" in lending was to a 3% growth rate versus almost triple that, or almost 9%, just before the recession began.

More recently, lending growth has stalled even in the negative-rate environment. Global market volatility in the second half of 2015, combined with the lack of any sense of urgency for borrowers and ongoing tightening of banking regulations and capital requirements all contributed to the stalling out of lending growth.

Following this week's rate cuts, European banks now have slightly better incentives to lend and just maybe borrowers won't have to worry about rates falling even further. What is not so certain is how much demand for borrowing there is in the private sector. This is where central banks' influence becomes more limited and is the crux of the issue for central banks everywhere. It is increasingly clear that central banks can't solve all the world's problems, especially in a demographically challenged world with slower growth potential than in previous decades.

What is certain is that even with an improved lending situation throughout 2015, inflation has moved nowhere, and it has dipped back again into negative territory early in 2016.

Looking at their most recent inflation projections, the ECB is clearly banking on persistent improvements in the inflation rate coming mainly from a more robust flow of credit (as many of Thursday's measures aim to stimulate) and the easing effects of low commodity prices that have been putting strong downward pressure on inflation rates around the world.

At the same time, GDP growth projections remain moderate. It appears that the ECB has come to terms with slower 1% to 2% real growth potential over the next three years, partially because of its bet for higher inflation. In addition, the labor and demographic environment in Europe is even less favourable than in the U.S., making the American growth rates of 2.2% to 2.5% largely unattainable across the Atlantic. In order to assess the effectiveness of the ECB's new monetary policy in the months to come, investors should pay close attention to the growth in lending (particularly to small- and medium-size businesses), and watch if meaningful improvements in the eurozone inflation rate begin to materialize.

Federal budget deficit remains relatively benign

For the first five months of fiscal year 2016 the federal budget deficit was US$353 billion, about the same as it was a year ago. However, April, when the government receives a substantial portion of individual tax receipts, is the key month for determining trends in the deficit.

In 2015, April government receipts were over 3 times the receipts in February, the slowest month for government receipts. With that caveat, things so far in 2016 are looking better than we would have guessed. For the full year, adjusting for month-end timing shifts, the Congressional Budget Office expects the budget deficit to increase from US$439 billion in fiscal year 2015 to US$500 billion in fiscal year 2016 (and US$544 billion if you include October, fiscal year 2017 payments that will be paid in September, fiscal year 2016).

With fewer changes in both healthcare and tax policy, both receipts and expenditure growth for the first five months showed considerable moderation compared with a year ago. Receipts grew 5.2% instead of 7.2% but that slowing was mostly offset by expenditure growth that dropped from 5.7% to just 4.2%. Combining the two, the deficit increased by less than 1%.

Though lower than in fiscal year 2015, healthy growth in collections from individuals (which relates to both better employment levels and higher investment gains) was the key driver of improved receipts. Last-minute changes in tax policy on corporate income in both years created slightly different anomalies. We'll need to see the March quarterly tax payments to gauge if the corporate declines are likely to continue. We won't be able to tell for sure, but that data should give us some clue as to whether this is just a timing issue or a longer-term issue with corporate profitability. In any case, corporate profits were about 11% of all government collections in 2015, which struck us as being smaller than we would have expected.

While government spending growth rates appeared to have slowed dramatically, from 7.4% for the first five months of fiscal year 2015 to 4.2% in 2016, the news isn't quite as bullish as it looks. The big jumps in 2015 were largely due to certain provisions of the Affordable Care Act kicking in. In 2016 there were no new provisions, so the growth rates fell accordingly in both the Medicaid and Medicare categories. Social Security spending growth rates dropped modestly, as an increasing number of retirees was offset by no increase in Social Security payment levels in January, as there was no increase in inflation, which drives the annual change in payments. The cumulative growth rate should continue to drop in fiscal year 2016 as more months with zero cost of living are included. Year-over-year growth, just February to February, was just over 1%, reflecting growth in the number of people collecting benefits. Medicare and Medicaid spending categories were up 3.6% and 6.4%, respectively. Hopefully, spending levels can be maintained at those relatively low rates.

Defence spending also continued its funk, actually declining ever so slightly from the year-ago level. We thought maybe the end-of-year-spending compromise bill might have begun to increase spending in this category some, but we guess it is going to take longer than we expected. Higher year-over-year inflation and higher debt continue to push interest payments up, though there has been some moderation here in recent months. Other spending, which is basically the normal functioning of government, increased about 4%, in line with recent trends and the growth in total spending. It's striking to us that just 31% of all government spending comes from this category with the bulk of the rest going to the three big social programs and defence. It would be impossible to make much new headway in the overall deficit levels even with relatively large cuts in the "other" category.

The relatively low spending increases will still manage to provide some help to the GDP growth rate as defence spending has at least stopped going down and spending in the other category accelerates modestly from a year ago. Given relatively low GDP growth rates, the economy can use any help it can get from government spending.

Next week retail sales, housing starts, CPI, industrial production and FOMC on tap

A flood of economic data is coming out next week, starting with retail sales on Tuesday. The consensus calls for a 0.1% decline for the headline number. The retail sales data is not adjusted for inflation, so the decline that many economists have penciled in is reflective of lower prices (particularly gasoline) rather than declining sales volumes. The retail sales control group that excludes autos, gasoline and building materials should advance by about 0.2% to 0.3% following a strong 0.6% increase in January. The savings rate still remains elevated, which could further boost consumption in February.

Housing starts will be released on Wednesday. The consensus calls for a solid rebound to 1,150,000, a number that would amount to a 4.6% monthly gain and a nearly 28% year-over-year change. (February last year was one of the weakest readings in starts in recent years, so the year-over-year data will become significantly distorted even if next week's numbers stay flat.) After two consecutive monthly declines, however, it would finally be reassuring to see starts rebound at least moderately.

Around the same time, the Bureau of Labor Statistics will publish the latest data on the Consumer Price Index. The index is expected to decline month to month rather significantly because of a big drop in gasoline prices in February (around negative 12%). That could translate into a negative 0.3% to negative 0.4% drop in month-to-month data, and drag down the headline CPI inflation rate to less than 1.0% year over year. The core CPI, however, is expected to advance 0.1%-0.2% sequentially, and remain around the 2.2% level year over year.

Industrial production headline growth likely to be a downer

Expectations for headline industrial production are for negative 0.2% and no growth in the more important manufacturing-only segment. Manufacturing employment data and hours worked suggest that it wasn't a great month for manufacturing, and the consensus estimates look too high to us. Nevertheless, we aren't too worried as recent reports have looked a bit better than we expected, and the year-over-year data is still likely to be quite positive. The headline number will likely look even worse as utility demand was likely unchanged and drilling activity probably had another bad month following a too-good-to-be-true number in January. As always, we think that despite a potential monthly setback to the overall report, manufacturing continues to trudge along the bottom, not showing much change for over eight months, despite all the gloomy assessments.

Fed not likely to act at next week's meeting

This week's ECB stimulus program further diminishes the already-slim probability of further interest rate hikes at the March meeting. A hike in the face of Europe's stimulus would drive the dollar higher, creating new problems of its own. We still worry that core inflation and services inflation is heating up, and we believe the Fed is, too. We will also be interested in seeing its economic forecast.