Although almost every piece of commentary I read about this week's market action centers on Greece and next week's possible default, the performance data points to something else. Equity markets across the world were uniformly down, but less than 1%, generally. I suppose the Greek issues could explain a slightly better performance in the United States compared with the rest of the world. However, a weaker bond market and stronger commodities seemed to suggest knock-on worries from the U.S. Federal Reserve's meeting last week, combined with stronger-than-anticipated economic data from the United States and modestly better manufacturing data from the EU and China. That better economic data raises the spectre of a stronger interest rate response from the Fed. Commodities were the best performer, eking out a 0.6% gain compared with minus signs in almost every other category this week.

U.S. economic news was robust this week -- just what the doctor ordered. More than one analyst at Morningstar pulled me aside on Monday and asked if I was OK after reading last week's gloomy assessment of the economy. This week I got just what I needed to pull me out of my funk. Existing and new home sales were both better than expected and canceled out last week's terrible housing starts news. Durable goods orders, ex-transportation orders, were up after a depressing seven months of decline. The consumption numbers for May were also as good as we expected. The GDP revision showed the first quarter wasn't so bad after all, though there was still a tiny shrinkage. A close reading of the GDP report for the first quarter and the strong May consumption report, combined with already known import data, suggest that it will be very hard not to grow U.S. GDP 3% or more in the second quarter, barring an inventory debacle, which is always a possibility. Until we get the second-month consumption number (May this quarter, discussed below), quarterly GDP estimates are pretty much a guess. After that data is released, the GDP estimates become more precise and are based on some relatively conclusive data points.

I feel like the economic data has been on a real roller-coaster lately and I admit to taking readers along for some of the ride. The truth is that the economy seems locked into a 2.0%-2.5% growth rate that almost nothing seems to be able to shake. Just as one category gets worse at the moment -- say, autos -- something mercifully comes along to offset it, like this week's housing data. And if one peels back the covers on an exceptionally good or bad piece of data, there is likely to be some type of data anomaly such as the West Coast port labour action or day count methodologies in the compilation of auto sales behind the off-trend data point. The auto anomaly combined with massive change in gasoline usage, which is probably not even physically possible, is behind May's red-hot consumption report, along with an unusual bout of monthly inflation. If the economic news seems too good or too bad to be true, it almost surely is. (I apologize to readers for last week's column, which turned out a little more depressing than I intended, perhaps because it's almost the Fourth of July and summer has yet to arrive here in Chicago.) Cheers to a continued slow but steady recovery with no boom or bust in sight.

Headline first-quarter GDP growth revised to a smaller decline

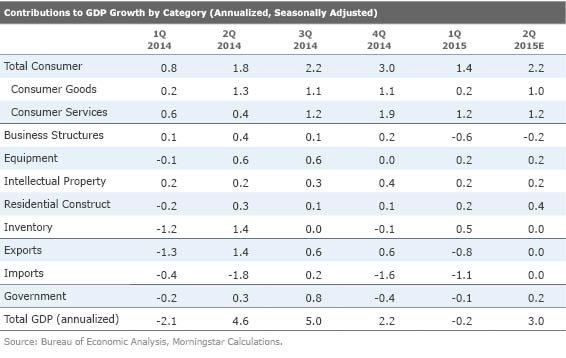

As widely expected and telegraphed by the Federal Reserve last week, the economic decline in the first quarter was not quite as dire as originally thought and certainly not as terrible as in 2014. Growth on a fourth-quarter-to-first-quarter basis and then annualized amounted to a 0.2% decline versus the previous estimate of a 0.7% decline but still not as good as the original estimate of a 0.2% growth rate. There were small upward revisions in most of the major categories and not one major "gotcha" type of adjustment. The large adjustment that many expected in health-care expenditures didn't really materialize; instead the adjustments were more in the camp of a little here and a little there. The broad contours of the report are largely unchanged. As is almost always the case, consumers, accounting for about 70% of the economy, continue to drive the economic bus along with a modest bump in inventories. Net exports were a real killer, knocking 1.9% off of what would have been a slow but still OK quarter without the issue.

While there are a few underlying issues with imports and exports, the real culprit was a massive dump of imports (which had been literally sitting just offshore for months) in March as labour issues at West Coast ports were resolved, allowing those ships to land and to be unloaded. April import data indicates that the great import rush is over and things will return to normal. The impacts of the labour action and its resolution are still turning up, sometimes in unexpected places. Retail sales suffered as there were often few goods to sell. And because there was a lack of supply, prices soared and then collapsed for common items like clothing. Now sales are looking artificially high as supplies of goods are replenished. Weather in some limited parts of the country might have played a role, too. Consumers didn't suddenly become great savers who were in a bad mode and despondent about their positions in life as many pundits would have you believe. That's pure malarkey.

We are expecting a large rebound in the second quarter with growth likely to be 3% or more without a lot of heroics. Our second-quarter forecast above basically shows the consumer returning to trend and the import/export mess disappearing in the second quarter. We are also hoping that the slowing in business structures, which were killed by the slowing of oil and gas drilling in the first quarter, will moderate in the second quarter and maybe get a little help from more spending on corporate buildings. That said, we shouldn't expect the back-to-back growth rates in the second quarter and the third quarter that approached 5% in 2014. First, the shrinkage in the first quarter wasn't as severe in 2015 as in 2014. The growth rates for the first quarter and the second quarter combined will not be much different in 2015 compared with 2014. It is a simply matter of a smaller down and a smaller rebound. Also, in 2014 an inventory drawdown (production slowed even more than purchases in the widespread bad weather) and subsequent rebound had a massive GDP impact. This year, weather hurt shopping but not production, so inventories actually grew, providing less opportunity for growth through inventory restocking, as clearly shown in the table above.

More important year-over-year data shows steady-as-you-go economy

We have long chastised the government's fixation on applying seasonal adjustments to data rather than calculating sequential quarterly growth and then annualizing those tiny quarterly changes. That really overemphasizes short-term changes and is predicated on the belief that we have mastered seasonal adjustment factors. We clearly have not and never will. To keep politics out of statistics, seasonal adjustments are calculated by a blackbox program and absolutely cannot be adjusted for common-sense shifts. I can name half a dozen adjustments that could be made easily but are not. The timing of ![]() Nordstrom's JWN anniversary sale and the change in summer shutdowns in auto plants have seriously messed with a lot of economic data sets over the past five years, but no manual adjustment is allowed. Looking at the year-over-year data sharply diminishes the impacts of shifts like these that wash out over subsequent periods. Even in ones that don't completely wash out, the impact in one month of faulty data is one month out of three in pure quarterly data and one out of 12 in annual data.

Nordstrom's JWN anniversary sale and the change in summer shutdowns in auto plants have seriously messed with a lot of economic data sets over the past five years, but no manual adjustment is allowed. Looking at the year-over-year data sharply diminishes the impacts of shifts like these that wash out over subsequent periods. Even in ones that don't completely wash out, the impact in one month of faulty data is one month out of three in pure quarterly data and one out of 12 in annual data.

In any case, the chart below shows the jumpy, conventionally stated quarter-to-quarter growth rates alongside comparisons of growth calculated same quarter to same quarter and then on a rolling 12-month basis at year-end. Looked at this way, the data is a lot less volatile and is a truer reflection of economic activity.

The table above also shows our best guess at GDP growth rates on the typical sequential basis and on our preferred methodology basis. The good news about our preferred methodology is that it shows a more stable, predictable economy. The bad news is that economic growth has been glued to the 2.2%-2.4% rate for the past four years with no real signs of acceleration. With slower population growth and an aging population that tends to be less interested in consumption, it may be hard to expect much more than this.

Headline consumption data good, but not quite as good as it looked

As we noted above, consumption is the engine that drives all growth in the United States (which isn't true of almost every other world economy). Therefore, both the retail sales and the monthly consumption reports are probably the most important data points in our economic playbook. The news for May was excellent. Headline consumption grew 0.9% (almost 11% annualized) between April and May, which drew praises across the financial media. The headlines are effusive: "Best in six years, splurged, surged, consumers spent freely after hunkering down." What a joke on so many levels. First, after adjusting for an unusually high inflation rate, the growth rate was a more down-to-earth 0.6%. And the previous month showed there was no growth at all. Average the two months together, and the growth looks a lot less exciting. And some of the mechanics of the auto sales calculations made May look wonderful (and the months on either side of May will look terrible). And gasoline sales allegedly fell apart in April and soared in May. The swing amounted to 0.2% consumption growth on a product whose basic demand has little reason to move at all. The month-to-month consumption volatility and slowly building annual consumption growth rate is clear in the table below.

I usually average these data points over three months but thought that even without averaging, year-over-year patterns still rule. Sequential monthly data is gibberish at best. The year-over-year data is trending better on a single-month basis, but I caution that when averaged, the improvement trend in consumption is a bit more muted. We graph some of the averaged consumption data later in this report.

Sector analysis is a little less hopeful than the combined data

Lately, my job seems to alternate between settling people down when they get too excited about the economy and boosting them as they become too depressed. It seems I have to change hats every couple of weeks instead of every six months. Right now, consumption growth looks stable when viewed in the most conservative light and booming if one just reads the headline month-to-month numbers. Some of the sector trends, while not pointing to a decline, show some surprisingly soft trends. While auto, furniture, gasoline and clothing were all stars in May, growth in restaurants, recreational services and vacation travel-related items all seemed to falter. These are key sectors to determine how the consumers feel, and they look softer than I would like. Too, some of the really positive consumption data looks suspect or at least short-lived. Strong May auto growth looks odd (days sales calculation that we have written about previously), clothing is being boosted by the return of imports to West Coast ports, and the gasoline surge is likely a statistical artifact that will go away in June. Again, no panic here because consumer incomes can support more spending, but this is not panic buying or a booming economy for anybody who looks under the covers.

Finally, consumption trending higher than incomes

Generally, improved incomes mean more spending. Consumers tend to spend whatever they make. In the intermediate to long term, it is nearly impossible for spending and incomes to diverge by much. The short run is a different story, often driven by psychology more than reality. From December through February the table above shows month-to-month income growth surged even as consumption stagnated. A lot of observers posited that the United States had again become a nation of savers. Give me a break. Just as the saving mantra was capturing the public eye, spending surged again and outpaced income growth over the past three months. Given the savings buildup, consumption probably has a couple of months more to run before income growth limits spending again.

Long-term pattern shows more potential for modest consumption improvement

The graph below shows that improved wages and total income are slowly pulling up consumption, which in general has been immune to short-term swings in income and wages. Shifting tax policy, especially on the wealthy, is driving some of the wage and income data crazy. However, those changes tend to affect the wealthy the most, and the wealthy change their spending habits little. That's because they already spend only a small portion of their total incomes and wages. In any case, wages and incomes both have been trending higher since 2014 and tax policies have finally stabilized, slowly but surely pulling consumption growth up to 3% or so from something that looked more like 2% at the beginning of the recovery.

Existing-home sales recovery is real, but will it last?

The sales of existing homes in the United States increased to nearly 5.4 million units in May, marking a 23-month high and a third consecutive month sales above 5 million. On a year-over-year, three-month average basis, the growth stood at 9.1%. This number has been improving for nine months after bottoming at negative 5.0% in September 2014, when the housing market froze because of a combination of higher rates, higher prices, and lower affordability. The inventory levels have also improved meaningfully, from 1.9 million units amid this winter to a much higher 2.3 million in May, or the equivalent of 5.1 months of inventory. That is certainly a piece of good news, as higher inventory levels should translate into less-severe price increases going forward. Shortages of homes for sale were widely blamed for the lethargic existing-home market in 2014. Regionally, on a year-over-year seasonally adjusted basis, the Midwest leads with a 12.4% growth rate, while the South, largest in terms of sales, is now the slowest in terms of growth, at 6.9%. Those are both good growth rates, considering that existing-home sales actually contracted by 3.1% in 2014.

One factor, among many, could be that the movement of mortgage rates is aiding this improved recovery. Two years ago, when the taper tantrum hit the markets, mortgage rates moved up relatively quickly, and homebuyers, afraid of further increases, decided to act quickly. About a month after the 2013 mortgage-rates bottom, pending home sales reached a high for that year. Those were the homebuyers who were able to lock in a good interest rate, and those who waited another month or two were probably disappointed as the rates reached a two-year high. Then mortgage rates started to decline again throughout 2014, bottoming out in early 2015. This time, consumers were much faster to notice the pattern and those who couldn't take advantage of low rates in the first half of 2013 probably got a second chance. As a result, pending and existing-home sales are now reviving the hope for this housing recovery. In the short term, it might seem like rising rates might be the final impulse many consumers need to stop postponing their home purchases. In the long run, however, higher mortgage rates -- moving up faster than incomes -- will definitely hurt affordability. Can this new housing revival survive?

Light at the end of the tunnel for manufacturing?

Manufacturing has been the unsung hero of this economic recovery, which began in 2009 with industrial production outpacing GDP for each of the past five years of the recovery, sometimes by a lot. At about 15% of GDP, it is even enough to move the economic needle. However, an end to China's ultrahigh growth rates (reducing the need to produce commodities), a slowing energy boom, and a likely peaking in auto production have slowed the manufacturing economy since summer 2014. Manufacturing industrial production growth in 2015 is likely to slow below our 2.4% GDP forecast. Still, some of the manufacturing data, including the ISM purchasing managers survey and the industrial production numbers, seem to be forming a bottom.

All of this background is a big buildup to the announcement that durable goods orders, excluding transportation products, a generally reliable indicator of future manufacturing growth, grew in May after seven painful months of decline. I should be quick to point out that the year-over-year, averaged trend is still negative and still down. Now we at least have one month of month-to-month improvement to back up some of our other positive metrics. Certainly no boom here, or even the definitive turn, but at least the decline has been arrested for now. From April to May, durable goods orders, excluding transportation, grew 0.3%. Year-over-year averaged data showed a slightly larger 1.7% decline, however, the orders are no longer getting worse by a full percentage point each month. This metric will still face some tough comparisons this summer, but a nice improvement is a mathematical possibility this fall.

New home sales strong, portending better housing starts and GDP growth

New home sales continued to outpace every other housing metric we track. This metric, along with the existing-home data discussed earlier, was the perfect antidote for the awful housing news we had last week. And, the really good thing about the new home sales data is that it's potentially the most leading of all are housing metrics. Permits data isn't bad, but the new home sales report includes buyers who purchased homes based on a picture, a plan, or a model home. The home purchase is likely not yet "permitted" let alone started. That's why it is a great offset to last week's horrible starts report and muddled permits data (overall permit growth was strong but all the permit growth was in just one region, prompted by an expiring tax credit).

The interest in new homes not started has been building for months but really busted out in May, as shown below. Overall, new home sales growth was an impressive 19%, blowing away most of our other metrics that have been hovering in the 10% range. Remarkably, sales of homes not started surged an even more amazing 32% and now comprises the biggest portion of the new home sales market.

The strength in new home sales overall has been building nicely all year with unit sales over 500,000 for every month of 2015 after never crossing that mark even once in 2014. Again, we always worry about Texas and the end of the oil boom, but for now the housing market seems to be taking this in stride. Whatever weakness we are seeing in more oil-dependent Houston is being offset by strength in Dallas. Any reader thoughts on the Texas housing market would be welcome.

Employment data and auto sales top a shortened holiday week

Employment data has generally been surging ahead of economic growth, suggesting growth is about to accelerate, employment growth hit the wall, or a big revision to the data sets. I am guessing that some combination of all of these will bring employment growth and economic growth into a more sensible alignment. Economists believe part of the adjustment will be in slower job growth in June with expectations that job growth will fall to 230,000 from 280,000 in May. That's higher than the year-to-date average and just about on our full-year forecast of an average of 230,000-250,000 jobs added per month. Like last month, the forecasts are unusually spread out. The bears, looking at 200,000 or fewer point to the oil patch and the disconnect between low GDP growth and high employment growth in previous months. The bulls, who seriously believe 300,000 jobs is a chip shot, point to job opening statistics that are absolutely massive, and suggest it is just a matter of time until at least some of that surge in openings turns into real jobs. Continued record low initial unemployment claims also bolster the bullish case. At a minimum, businesses are clinging to current employees like glue. My guess is the consensus is not too far off the mark and I am going with job additions of 225,000. I will be the first to admit that this is more of a gut feeling related to the growth rate disconnect (which has been equally present but worthless over a series of excellent job reports), and the mathematical weight of the bull case is pretty impressive.

Auto sales surged in May, partially because of real demand and partially because of a calendar anomaly that artificially boosted sales. Most auto analysts -- but not many economists -- are on to this hidden helper. It's the main reason for the May consumption blowout we discussed above. Analysts are projecting auto sales to drop from 17.8 million units in May to 17.2 million units in June. That's a measly 2% growth rate compared with a year ago, perhaps pointing to an end, or at least a plateau, of the great auto boom. If that forecast proves accurate, it will put a big hole in the June consumption report that will be hard to replace.