We have met our enemy and he is us.

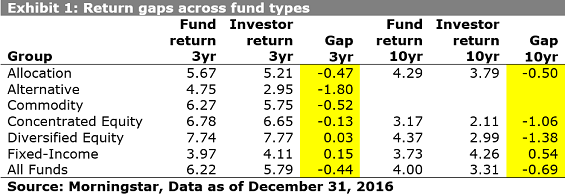

The average Canadian investor has lagged the average fund for the last 10 years. Through December 2016, the average Canadian diversified equity fund returned 4.37%, yet the average diversified equity fund investor earned 2.99% over the decade--a 1.38% gap. This gap is costly: In dollar terms, the difference between the two numbers equates to nearly $20,000 in lost gains on a $100,000 investment.

When all fund categories are considered, the average Canadian fund gained 4% over the decade, versus 3.31% for the average fund investor. This disparity was the largest among the seven major fund markets studied in Morningstar's forthcoming white paper titled Mind the Gap.

The paper compared funds' time-weighted returns -- the method almost always used to display total returns -- to their money-weighted returns across major asset classes. Money-weighted returns, or investor returns, use a fund's monthly asset flows to measure the return most fund holders captured.

Figure 1 (below) measures the Canadian investor return gap across fund types over three- and 10-year trailing periods.

Investors only capture a fraction of their fund's time-weighted returns because they tend to choose investments that already have done well and sell too quickly when their holdings struggle. Put another way, investors buy high and sell low, leaving a chunk of their fund's returns on the table.

To be sure, investor return data should be taken with a grain of salt. Random factors, such as when a fund opened for business, can influence investor returns. Our data measures investor behaviour in aggregate, so the general conclusions we draw from it won't necessarily be true for every fund. Also, our calculations measured the return gap for funds that provided us with sufficient asset data. We don't know if investors behaved differently at funds not included in our study.

That said, our research offers meaningful insights on how investors can improve outcomes through better behaviour.

Don't do something, just sit there

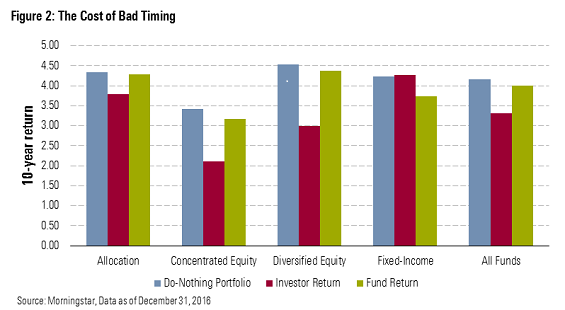

Investors often confuse action with progress. Sometimes the best thing to do is nothing at all. Our study tested this proposition by asset-weighing returns based on where assets were at the beginning of each period. We found the do-nothing portfolio produced slightly better results than both investor returns and a straight average of returns in every asset class except for fixed income, where investor returns came out on top.

For example, the typical diversified equity fund investor would have had a return of 4.5%, a hair better than the 4.4% average fund return and well ahead of the 2.9% average investor return. Figure 2 (below) illustrates 10-year returns for the do-nothing portfolio, total returns, and investor returns across fund types.

Dollar-cost averaging is your friend

Investors usually make their biggest mistakes when their emotions get the best of them. The best antidote to emotion-driven decision-making is discipline. One great enforcer of discipline is dollar-cost averaging, the practice of investing regular amounts at pre-defined intervals. This practice removes the primary cause of poor investor returns -- bad timing -- from the investment process.

Such discipline does wonders for investor returns. In Australia, every working person invests a slice of their paycheques in retirement funds (known as "superannuation" funds) as part of the country's government-mandated retirement system. These funds' investor returns significantly outpaced their total returns over the past decade. In fact, the average Australian outpaced the average superannuation fund return by a remarkable 2.4 percentage points annually.

Unfortunately, we can't say for certain if Canadians enjoy the same success in their workplace retirement plans. Most retirement plans invest in non-public pooled funds, which weren't included in our study.

Volatility could be your enemy

Historically, investors have used volatile funds poorly. High volatility on the upside lures investors with the prospect of big gains, while downside volatility prompts them to flee for fear of losing money. Both behaviours drive the buy-high, sell-low pattern that results in subpar investor returns.

Less-volatile fund types tended to deliver better investor returns. Over the 10-year period, the return gap was lower among allocation funds, whose mix of stocks and bonds smooths volatility, than pure stock funds. And the average bond fund investor outpaced the average bond fund.

Even so, the relationship between investor returns and volatility wasn't clear cut. Surprisingly, bond fund investor returns improved as volatility rose. That may be because bond investors have been rewarded by taking on added risk over our study period. With yields falling over most of the decade, taking interest-rate rate risk paid off. In a less-forgiving environment, investors may not use bond funds as well.

Know thyself and thy funds

What's true of traditional time weighted returns is also true of investor returns: Past performance won't necessarily predict future results. When markets no longer reward risk-taking, investors may find more-volatile funds harder to stomach. This underscores the importance of knowing not just how a fund has performed but understanding how it invests. The dangers of traits like portfolio concentration or heavy interest-rate and credit risk can lay hidden for long stretches but will likely resurface at some point. Investors must know themselves well enough to know if they can weather the inevitable storms before taking these risks.