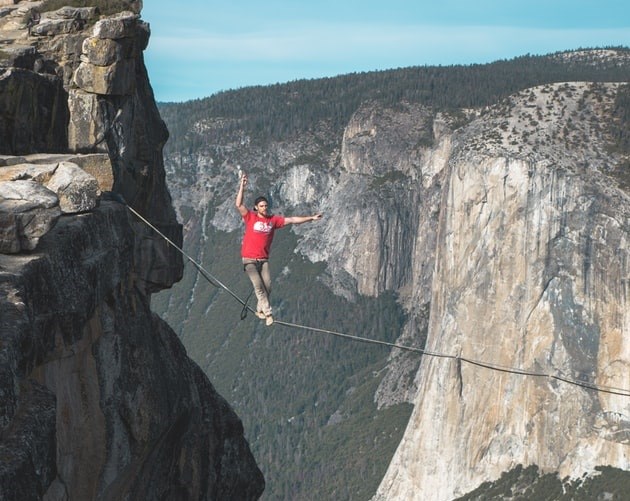

Investing is an exercise in calculating a host of factors to determine the attractiveness of companies. And while it may appear to be more rational to indulge in long-term forecasts, it may be more productive to use filters, such as rules of thumb, to conclude whether a stock is a viable choice, says Karan Phadke, an equity analyst at Calgary-based Mawer Investment Management Ltd.

“One of the biggest things is the role that luck and randomness plays, especially in driving exceptional long-term outcomes,” says Phadke, a member of the team that manages the five-star $3 billion Mawer Global Small Cap Fund A.

For the 12 months ended Feb. 28, the fund returned 7.85%, versus -5.33% for the Global Small/Mid Cap Equity category. On a five-year basis, the fund averaged 9.03%, compared to 2.45% for the category.

Phadke attributes the fund’s strong returns to a mixture of Mawer’s culture of independent thinking and old-fashioned luck. “We don’t know to what extent luck played a role. But we like to believe that the culture and process and looking for the right filters will put the odds in our favour. Yet there will always be an element of luck, too.”

Phadke argues that there are individual agents within a social or economic system who will adapt and react and cause other agents to adapt to their behaviour. This creates a kind of reflexive or feed-back loop, with some unpredictable outcomes. “Things don’t really settle down. In a lot of these systems, things are not normal for very long because there is always something new that comes along and causes things to diverge from what you would expect,” says Phadke, a native of Johannesburg, South Africa who joined Mawer in 2016 after stints at the CPP Investment Board and management consultants A.T. Kearney and earning a BSc in actuarial mathematics at University of Toronto.

Disruptions difficult to predict

Consider what happened in the 1980s when the VHS format competed against Betamax in the so-called video cassette recorder wars. Both started with similar technologies and market shares, although some argued that Betamax was a superior format. “Even though they started out in the same place, due to some randomness and the way people adopted them VHS took the lead and became the dominant format just because of the way that history played out,” says Phadke. “Even if you have a small lead over another technology, there is a network effect. So the more people use the technology the better the product gets. Those small differences at the start [between products] can compound over time, and lead to unexpected outcomes.”

Another example that Phadke points to is the rivalry between social networking web sites Myspace and Facebook (FB). “It was very difficult to predict that some university upstart called Facebook would completely overwhelm Myspace. No one could have predicted it,” recalls Phadke. “Looking back, people will say, ‘It’s obvious that Facebook would win.’ But I would posit that it was not obvious. It was a case of small differences [in format] that compounded over time. With luck and randomness thrown in, that’s what caused Facebook to become dominant.” In a similar vein, Phadke points to how Apple’s iPhone overtook the Blackberry, contrary to many people’s expectations and went on to have a market cap of over US$1 trillion.

“Sometimes these small differences compound over time. Even a small difference in the beginning [of a forecast] due to luck or randomness can lead a system to a different place five or 10 years out. Social and economic systems are even more difficult to predict or make accurate long-range forecasts,” says Phadke.

Complexity doesn’t beat complexity

Phadke draws many of his observations from German psychologists such as Gerd Gigerenzer, the author of Heuristics, the Foundations of Adaptive Behavior, as well as Nasim Taleb, author of The Black Swan, and U.S. economist W. Brian Arthur, a teacher at the Sante Fe Institute for Complexity and one of the early researchers in field of complexity theory. “What they have in common is that long-term forecasts are exceptionally difficult. Second, there is a lot of randomness at play and small changes can compound over time and cause big differences, which are inherently difficult to predict. Third, the way you deal with complexity is not by trying to predict an outcome, but by having a filtering mechanism or using rules of thumb.”

It can’t be said that rules of thumb, or heuristics, are the only way to gauge a company, or that they are perfect. “But in our experience, they work surprisingly well and are pretty robust under a lot of uncertainty,” says Phadke. “People have a tendency to fight fire with fire or expressed another way, complexity with complexity. There is a bias to believing that a complex difficult problem is best tackled with a complex difficult solution. The term that our chairman, Jim Hall, uses is ‘filtering not forecasting.’ This is what we mean by heuristics, or using broad filters that put the odds in your favour, as opposed to specific predictions.”

The difference between the two, notes Phadke, is that a specific forecast does not account for the randomness in the world. Or, to put it another way, he maintains that the weakness of a specific forecast is that it “overfits” the data. “Just because the past looked a certain way, does not mean the future will look the same.”

In selecting stocks for Mawer Global Small Cap, Phadke works closely with lead manager Christian Deckart, deputy chief investment officer and co-manager Paul Moroz, chief investment officer and John Wilson equity analyst. They seek firms that meet three initial characteristics that they believe will work in their favour: wealth-creating companies, excellent management teams and stocks that are trading at a discount to intrinsic value. “These are the broadest filters that we apply not just to the global small-cap fund, but across the firm,” says Phadke. “Within the small-cap fund, we look for more specific characteristics.

Broad bets with key factors over focused filters

Among the factors they look for are recurring revenues, dominant market shares, firms that are managed by owners or companies with high incremental returns on capital. “You want to keep the filters pretty broad. You might look at filters such as market share or recurring revenues. But you don’t want to go too much further, because then it becomes too much of a forecast and that won’t account for the inherent unpredictability of the world.”

One top name in a portfolio with 70 holdings is Bravida Holding AB (BRAV), a Swedish firm specializing in electrical and heating ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) services for commercial clients. “Typically, most HVAC services are done by Mom and Pop operators. Bravida is professionalizing the business or industrializing a craft. And they are the number one player in Sweden,” says Phadke. “Despite this, they only have a 6% market share, so it’s a very fragmented market. They are slowly acquiring the Mom and Pop operators and putting them on their platform, centralizing their procurement and purchasing, and helping to improve their margins and efficiencies.” Acquired in late 2018, Bravida stock is trading at about 18 times forward earnings. According to Phadke, it could generate an internal rate of return of up to 9% in some scenarios.

Another favourite is Fielmann AG (FIE), the largest eyewear retailer in Germany. The firm began in the 1970s and benefitted from a public-funded insurance plan. It now accounts for 53% of the market, or twice that of the nearest competitor. “Their glasses are up to 30% cheaper than their competitors because they produce their glasses in-house and have a very large assortment and get a lot of customer traffic. They continue to grow due to ageing demographics. And 30% of the market is held by Mom and Pop shops that don’t have the scale to compete. That’s where Fielmann is taking market share from,” says Phadke. Acquired in late 2018, the stock is trading at a high multiple of 36 times trailing earnings. “It’s a very stable business that continues to grow at 5-10%,” says Phadke, adding that the stock could generate an internal rate of return of up to 6% in some scenarios, versus German government bonds that have negative yields.

Standards of long-term success

Learn how ESG builds sustainable profits in our latest report

.jpg)