This column was originally published on Aug. 21, 2015.

One basket, one egg

In 1994, two professors, Richard Thaler and J. Peter Williamson, asked the question: Why not put it all into stocks? Their query was more than a mere academic exercise, as the article, "College and University Endowment Funds: Why Not 100% Equities?," was published in a journal aimed at institutional investors, The Journal of Portfolio Management. The authors intended to be provocative, but they also believed they were raising a serious point.

For the most part, their effort earned hoots from financial advisors and the general press. The argument smacked of bull-market optimism; it seemed the sort of thing that cocky people wrote late in a market cycle. Besides, it wasn’t practical. Who could withstand the full, unalloyed impact of a stock-market crash? Not many of the advisors’ clients, nor the press’ readers, either.

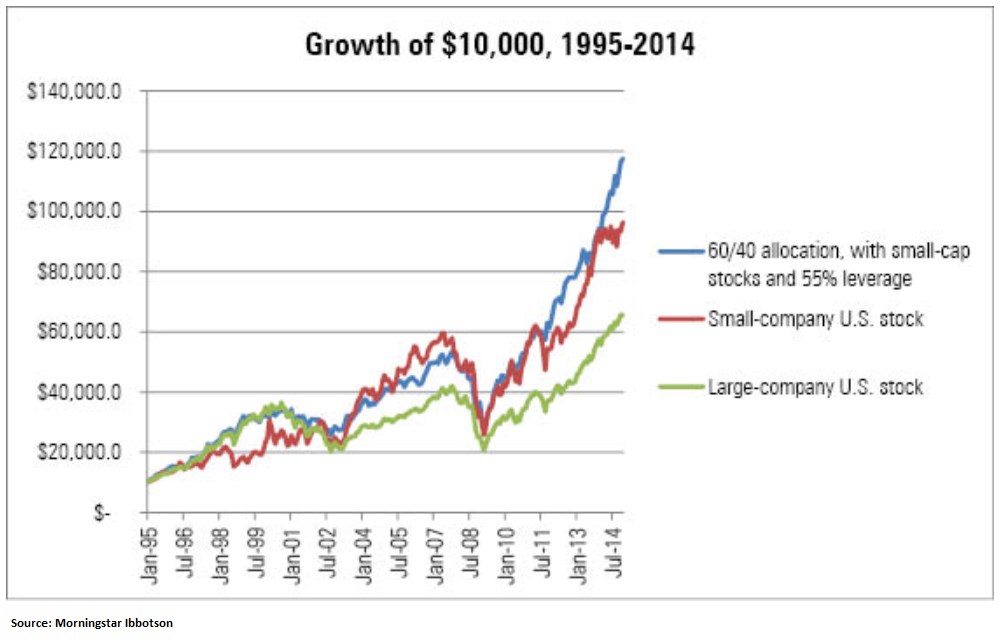

On the other hand, the suggestion sure did work. A US $10 million lump-sum investment placed into Ibbotson’s U.S. Large Company Stock Index on New Year’s Day 1995 would have ballooned to US $65.5 million two decades later. For comparison’s sake, $10 million stashed in the Case-Shiller Los Angeles Home Price Index would have been worth less than half as much, at US $29.8 million.

There were two very rough patches along the way. The all-stock portfolio slid from US $36.5 million in summer 2000 to just over US $20 million by September 2002. Even grimmer was the plunge from US $42 million in late 2007 to $20.7 million in early 2009. The article assumes that with a time horizon of roughly forever and the financial flexibility to adjust spending, endowment managers would have stayed the course. Perhaps--but their discipline would certainly have been tested.

Still, thanks to quiescent inflation, the all-stock portfolio had a positive real rate of return throughout the 20-year period. Better yet, even at its 2009 nadir its value was far ahead of what the national home-price index had generated over the previous 15 years and fully competitive with the value of the top local markets: Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. When even the least-favorable results keep pace with San Francisco real estate, that is mighty fine performance indeed.

Before we congratulate the authors too heartily, it should be noted that in that particular 20-year period, almost all financial darts were winners. An all-stock portfolio was scarcely the only path to prosperity. For example, the Ibbotson Long-Term Corporate Bond Index also easily beat real estate, rising to just shy of US $50 million. And, demonstrating the power of rebalancing, a 60/40 stock/bond blend gained almost as much as did the pure-stock portfolio, growing to US $62.3 million.

Egg substitutes

Which leads us to the second critique of the 1994 paper.

In the Winter 1996 edition of The Journal of Portfolio Management, Cliff Asness of Goldman Sachs (who would later form his own hedge fund company, AQR) diverged from the general media’s complaint by accepting the all-stock portfolio’s risk. After all, endowment funds have a time horizon of roughly forever and, presumably, the discipline to shrug off short-term disappointments. So why shouldn't they aim higher than the traditional 60/40 balanced fund? Asness did not quarrel with that part.

However, he argued, the authors’ implementation could be improved. Two alternative portfolios would give significantly higher returns, at roughly similar levels of risk. The first suggestion was to retain the 100% equity position but to substitute Ibbotson’s U.S. Small Company Stock Index for its large-company version. The second and more ambitious version was to retain the 60/40 allocation, once again substituting small-cap stocks for blue chips, then to leverage that position by 55%.

Both portfolios performed fabulously--I suspect better than even Asness would have believed.

The 100% small company portfolio soared to US $96.5 million. While the 2008 market crash hurt it even more than the original large-cap portfolio, in percentage terms, it fell from a higher place, so that it bottomed in 2009 at US $25 million rather than the large-company portfolio’s US $20 million. And it largely dodged the previous 2000-02 bear market, which mostly affected the giant tech companies. By any reasonable measure, the 100% small company portfolio outperformed the original, large-company version.

The leveraged portfolio was even more spectacular, checking in at US $117.5 million. A 12-bagger in a mere 20 years! For a basket of securities, rather than a single (and fortunate) stock! The going does not get any better than that. In addition, the portfolio avoided significant losses except for the 2007-09 time period, where both in percentage terms and in the dollar amount at its low point, it bested all tested alternatives--both flavors of 100% stock portfolios, the unleveraged 60/40 balanced portfolio, and the all-bond portfolio.

Takeaways

You and I won't be executing the leveraged strategy anytime soon. For that portfolio, Asness specifies a borrowing rate equal to the interest rate on one-month Treasury bills (which is how performance for this column was calculated). Good luck with that. My brokerage firm quotes me a margin interest rate of 6.50%--far above the one-month Treasury rate. The leveraged portfolio would be a pooch paying anything like that price.

So, unless an institution executes the leveraged balanced strategy by borrowing at very low interest rates, and offers to sell you a piece of that portfolio while charging only a modest management fee, that approach is for practical purposes unavailable. The leveraged portfolio remains as it was born, a picture on a theoretical Security Market Line.

We might, on the other hand, consider an all-equities portfolio. Whereas none of us have the centuries ahead of us that Yale can expect, we may have a time horizon of several decades--perhaps long enough according to both the historic performance figures of equities and to theories of their expected returns (shaky as they are), to justify having everything in stocks. (For more on the argument that equities might be safer than bonds for those with long time horizons, see Bill Bernstein's Rational Expectations: Asset Allocation for Investing Adults.)

Thaler and Williamson would surely have granted, as they wrote to advance a general idea rather than to propose one particular asset allocation, that risk level can and should be achieved by something other than all U.S. stocks, all blue chips. A diversified mix of stocks of all varieties, plus other assets (such as real estate or exotic bonds) that are deemed to offer similarly high future returns is the sounder approach. By no coincidence, that pretty closely describes how most long-dated target-date funds are managed.

Six years into a stock bull market, I won't pound any e-tables urging readers to buy more stocks. This column, as always, is intended to explore ideas and think through consequences, no more. I will note, though, that the 1994 article was launched at what was then perceived to be near a market top, only two years before Alan Greenspan's famous comment that U.S. stocks were perhaps priced for "irrational exuberance," and yet the all-equities advice ended up working out well. Predicting the future is no easier for pessimists than it is for optimists.

Note: If I were to write this column today, it would read differently, because I would be wary of suggesting that people buy more stocks 11 years (!) into a bull market. However, the topic remains evergreen, as witnessed by the fact that prices for U.S. stocks are up 75% (with total returns being higher) since this article was published.