The sinful seven

The stock market's reaction to the coronavirus was big news. Last week, the Dow Jones Industrial Average's performance gathered more cyber ink than anything but the progress of the virus itself (and, perhaps, the South Carolina Democratic primary). The largest point decline in the history of the index! However, that information wasn't terribly helpful, because the DJIA had doubled over the past seven years, thereby rendering moot comparisons with previous drops.

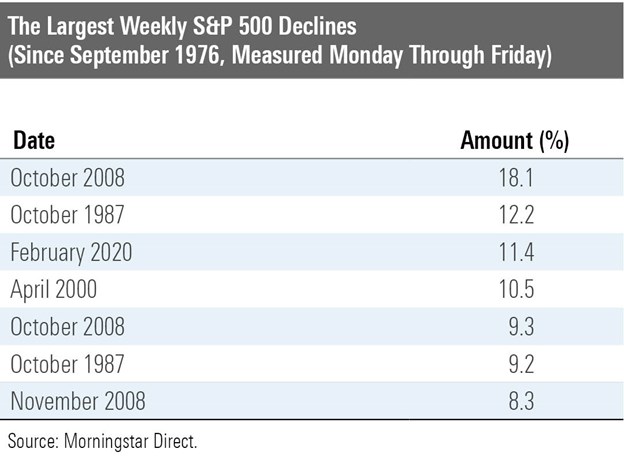

Percentages were needed to understand the context, preferably from a broader index than the 30-stock Dow. Several sources duly obliged, reporting that the S&P 500 had dropped more than 11% from Monday through Friday, which made for its biggest weekly decline since the 2008 financial crash. That was helpful, but incomplete. More history would be required to establish the proper context.

Enter Morningstar's database, as it contains Sunday-through-Saturday total returns for the S&P 500 since 1988. What's more, as Vanguard 500 Index (VFINX) existed for 12 years before Morningstar's weekly index data begins, we can extend the analysis by using the fund's returns as a market proxy. That makes for 2,260 weekly observations, starting in the summer of 1976.

The upshot: Last week's showing was indeed rare. The final week of February 2020 rates as the third- worst Monday-through-Friday by performance by the S&P 500 since 1976. There haven't been many weeks that placed close to it, either. Lowering the loss threshold to 8% admits only four additional entrants, for a grand total of seven weeks over 43 years. The news coverage was merited.

Here are those seven weeks:

The previous six

Until now, the largest weekly declines since the mid-1970s came solely from three years: 1987, 2000, and 2008. While the details of those markets vary widely, they share an underlying foundation. In all three cases, investors worried about what governments could not do.

In 1987, many believed that the United States would inevitably sink into recession, because rising interest rates--which could not be prevented, as they were accompanied by worrisome omens of inflation--would squeeze consumers who had accumulated record amounts of debt. Government intervention could not prevent that outcome. (As it turned out, those fears were misplaced; the danger resolved itself, largely on its own, and the economic expansion continued for several more years.)

The problem in 2000 was less the economy--although that expansion was getting long in the tooth--and more abnormally high technology stock valuations. No regulator or legislator could prevent what must follow. Either technology companies would need to post earnings that exceeded even the most optimistic expectations, or their stocks would get crushed. They got crushed.

Things were even clearer in 2008. By late summer, when Lehman Brothers imploded, there was no doubt that the global economy was about to go Kersplatt. Governments around the world intervened mightily, injecting capital aggressively, but their efforts would never suffice. The financial system was too rickety. The giant banks were forced to contract and to clean up their balance sheets, thereby sparking recession across the developed markets.

Government Solutions

Today's situation is different. From an investment perspective, rather than the human one, the concern is not that governments have no power or will do too little, but rather than they will do too much. If they did not intervene at all, many people would die, but the stock markets would not necessarily be much affected. On the other hand, if they intervene substantially, the people will fare better, and the markets worse.

To explain: Without government intervention, the coronavirus would surely infect a large portion of the global population. The preliminary evidence suggests the disease would pose great danger those who are above the age of 70 and who have pre-existing conditions; moderate danger to those between the ages of 50 and 70 and who have pre-existing conditions; and only modest danger to the rest.

The latter group represents 85% of the world population and an even higher percentage of its workers. Therefore, if the coronavirus were permitted to do its thing without government involvement (although presumably with individual solutions, such as affected individuals quarantining themselves at home), it would be unlikely to greatly harm productivity.

100 Years Ago

For a historical comparison, consider the Spanish flu pandemic, which ran from early 1918 through late 1920. It killed 40 million people globally for an overall fatality rate of 2%. The United States fared significantly better, losing about 0.5% of its population. However, unlike with the coronavirus, the Spanish flu strongly affected young adults, as those aged from 20 to 40 accounted for about one third of the pandemic's U.S. deaths.

During that three-year period, U.S. stocks gained an annualized 7%. They rose during the first two years, then slumped in 1920 as a depression arrived. Historical accounts of the depression's cause generally name rising inflation, which spurred the Federal Reserve to push up short-term interest rates to 7% (!), which then caused deflationary expectations. The effects of the Spanish flu barely receive a mention.

One hundred years later, the world’s governments will not permit the coronavirus to run its course, with the economy chugging along even as the hospitals start to fill, as was the case with the Spanish flu. Today, people expect governments to guard as vigilantly against the spread of diseases as they do against foreign invasion. Yesterday, for example, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe requested that Japan's schools be shut down entirely until early April.

Such actions cannot help but to have knock-on effects. Conducting business as usual while a virus rages is conceivable, albeit callous, but doing so while schools are closed, employees are quarantined, and travel restricted is utterly impossible. Chinese production plummeted in February because of its coronavirus controls. That slowdown doesn't figure to end anytime soon. Meanwhile, other countries will institute similar measures, which will induce similar effects.

Wrapping Up

Last week's stock market decline strikes me as rational. Implicitly, today's investors will accept a recession, with accompanying lower stock prices, in exchange for potentially controlling a pandemic. That's an eminently reasonable decision--but it does present the possibility that last week's stock market losses were the beginning of a sell-off, not the end.