Global financial markets are in disarray and panic is evident. Equities are experiencing panic selling and bonds panic buying. An oil price war has erupted between Saudi Arabia and Russia which will damage all players in the industry. Highly leveraged U.S. shale producers appear to be Russia’s target, but all economies dependent on the oil price will suffer should the war be of meaningful duration. This adds another layer of confusion to the coronavirus anxiety already testing the resolve of investors.

High beta stocks are at risk and technology names are core holdings in many exchange-traded funds (ETFs) where the blow torch has been turned on valuations. The redemption phase has started and the now agitated passive investor has been jolted from the complacent couch as fear replaces greed. As the ride gets bumpier by the day, more and more investors are asking, “Are we there yet?”

Recall Nouriel Roubini’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (my terminology) Xi Jinping of China, Vladimir Putin of Russia, Kim Jong-un of North Korea and Ali Khamenei of Iran. Roubini postulated Iran could escalate a conflict with the U.S., “risking full-scale war on the chance an ensuing spike in oil prices would crash the U.S. stock market, trigger a recession. And sink Trump’s re-election prospects.” But Putin has been the first to enter the fray in a bizarre way by refusing production cuts to support the oil price; and the left-field reaction of Saudi Arabia (a U.S. ally) to slash the oil price only adds to the intrigue.

Should the oil price remain depressed for some time, the soft underbelly of highly leveraged U.S. shale producers will be exposed. Already US energy bonds have taken a beating, with spreads widening dramatically. And the coronavirus is choking corporate cash flows as global supply chains seize up. While the pandemic is headline-grabbing, there is the potential for a serious financial contagion, engulfing both credit and equities markets.

And no, we aren’t there yet. Those suggesting it’s the shortest bear market in history should count to 10 slowly—one Mississippi, two Mississippi …

It’s difficult writing a weekly newsletter when the markets are gyrating daily. It is always better to stand back and continue to prosecute your longer-term thesis. So …

Knock, knock: Who’s there?

Mean,

Mean who?

Mean reversion

Regression to the mean or mean reversion is primarily associated with statistics. The concept was first popularised by Sir Francis Galton in the 19th century and was based on his works on genetics and hereditary stature. In the investment arena, it has a different meaning and is used to describe how extreme short-term returns are usually more stable in the long-term. A period of low returns tends to be followed systematically by a compensating period of higher returns.

Over the past decade, stock market returns have significantly exceeded the long-term average. The gains have been driven by the well-known largesse of global central banks, whose behaviour has also meaningfully diverged from the longer-term pattern, and which at some point will also revert to the mean.

Elevated stock market returns have driven wealth beyond the dreams of most mere mortals. Niels Jensen’s highly regarded Absolute Return Letter argues strongly that “wealth in society cannot outgrow nominal GDP forever.” Over the past decade, wealth has meaningfully outgrown nominal GDP and reversion to the mean in this case is likely to have widespread repercussions in financial markets. The U.S. has been the greatest beneficiary of wealth creation as entrepreneurial disrupters have cut a swathe through the behavioural norm.

Thanks to the behaviour of global central banks, the returns on risk assets have generally been significantly above long-term averages. But risk-taking has also been pushed to an abnormal level, which is all well and good, until it is interrupted by a black or white swan swimming across the previously placid lake.

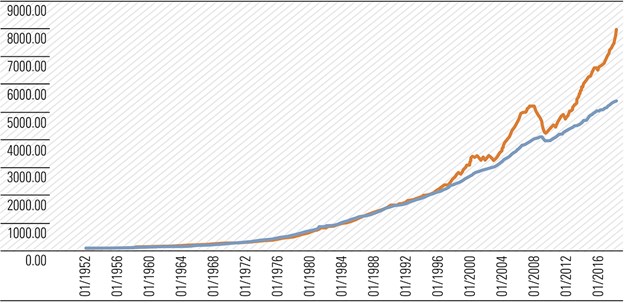

Exhibit 1 shows the close long-term relationship between US household wealth and nominal GDP up until the mid-1990s. The relationship then parted and the gap has widened ever since, with brief contractions in the wake of the dot.com collapse and the GFC. Remember GDP growth drives wealth not the other way around. Wealth growth is society’s feel-good factor. The lack of it or the widening wealth gap has sponsored the rise in populism underpinning the rise of the Trumps and Johnsons of this world.

Exhibit 1: US household net worth vs. nominal GDP

Source: Zero Hedge

As Morgan Housel, partner at Collaborative Fund, former Wall Street Journal columnist and the author of the essay “Five Lessons from History” quaintly asks:

“What kind of person makes their way to the top of a successful company or a big country?

“Someone who is determined, optimistic, doesn’t take ‘no’ for an answer, and is relentlessly confident in their own abilities.

“What kind of person is likely to go overboard, bite off more than they can chew, and discount risks that are blindingly obvious to others?

“Someone who is determined, optimistic, doesn’t take ‘no’ for an answer, and is relentlessly confident in their own abilities.”

And as Jensen points out, every country has a “well-established mean value when you measure wealth relative to GDP.” The long-term mean value of wealth to GDP in the U.S. is 380%. A few weeks ago, it was 520%. With the Dow down near 20% the gap is now less, but it is still meaningful before the reversion process is complete. The mean reversion in U.S. wealth is likely to go hand in hand with the reversion of U.S. equity prices, some of which is currently unfolding before our perhaps astonished eyes.

Equity valuations have been stretched, benefiting from low bond yield-related discount rates used in discounted cash flow models. The higher the valuation, the lower the medium to long-term returns. Consequently, the purchases of the past six months are likely to return around 5% per annum over the next 10 years, rather than the double-digit returns of recent years.

Credit spreads opening like the Red Sea

The anxiety driven by coronavirus and an oil price slide has triggered a contagion in credit markets. The spreads on energy, airline, leisure and accommodation company bonds have increased meaningfully. These are industries whose cash flows and earnings are immediately under pressure and the net will widen as global economic activity contracts and the chances of a recession increase.

Credit markets have already seized up, and companies will find it increasingly difficult to roll maturing debt and the interest rate will jump substantially. Zombie companies face the very real prospect of insolvency and unsecured bondholders, default or worse. Unlike the GFC where banks were exposed to subprime mortgage debt, U.S. corporate debt is held to a large degree by institutional and retail investors. The risk level across the financial system is less and government bailouts, are not likely to be as forthcoming.

When the entire (3-month to 30-years) U.S. Treasuries yield curve was below 1.00% recently the level of concern should have been extreme. Guggenheim Investments’ Global Chief Investment Officer and Chairman of Investments Scott Minerd has admitted their “proprietary models indicate that fair value on the 10-year Treasury note will reach -50 basis points before year end and the possibility that rates could overshoot to -2 per cent.” CNN’s Fear and Greed index for the U.S. equities market is currently deep in the Extreme Fear zone.

Guggenheim estimates “there is potentially as much as a trillion dollars of high-grade bonds heading to junk” and that supply “would double the size of the below-investment-grade bond market.” Minerd soberly, perhaps alarmingly, continues, “The prospect of a crisis at maturity—that a borrower with maturing debt finds it impossible to roll the debt over to pay it off—is a very real prospect even for companies that are solvent. It has happened before, and it will happen again.”

Should central banks be stress-tested?

Since the GFC, commercial banks around the world have been regularly stress-tested to ensure those risky practices of the past have not reappeared. The unconventional practices of central banks in a post-GFC era have also been risky and perhaps they too should be stress-tested.

Former Federal Reserve (the Fed) board member Richard Fisher, who was chief executive of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas between 2005 and 2015 and a member of the Federal Open Market Committee, said the Fed board had “lost control of the yield curve”. The Bank of England refers to the U.S. 10-year treasuries as “the key marker bond rate in the world”. The 10-year yield hit 0.3137% on Monday, while the 30-year fell below 1.00%. Just five months ago it cracked 2.00% for the first time. The rate of the decline in US bond yields has been staggering.

The Fed’s balance sheet continues to expand, now with total assets of US$4.24 trillion, up US$480bn from US$3.76 trillion, in just over six months since 28 August 2019. The peak was US$4.46 trillion at end June 2017.

When commercial banks’ balance sheets are stretched, as they have been in the post-Hayne environment, new equity is raised. What does a central bank do when its balance sheet is stretched? We read, whether reassured or not, the Reserve Bank of Australia has multi-billion dollar emergency funding lines on standby to provide liquidity to banks if global credit markets remain tight. Are funding lines unlimited?