If you were born after 1985, please skip this first paragraph.

The term FOMO is an acronym that stands for the ‘fear of missing out’, originally coined by Patrick J. McGinnis in 2004 and used largely by the highly connected millennial and Gen Y generations. This ‘fear’ is spurred on by the fact that many of us are inundated with updates about our social circle’s activities, to the point that some individuals feel like they are ‘missing’ out if they are not actively participating in conversations or activities around them. The term is generally regarded with a negative connotation, sometimes contributing to a person’s indecisiveness or overcommitting to obligations.

Although FOMO can often be waved off as a novelty term, the concept becomes very real when it comes to investment decisions. In fact, I would go as far as saying that having FOMO is the correct instinct when it comes to investing, especially now amidst the severe market drawdowns and widespread panic that we’ve been experiencing.

In the recent past I’ve referenced work by Dr. Paul Kaplan and Dr. Maciej Kowara both in terms of the fallacies of dollar cost averaging over months versus lump sum investing, as well as the concept of critical months (months that investment funds’ returns depend on to beat the benchmark). Both pieces of research point to the inevitable fact that a month of performance can make all the difference in investor return. However, during volatile times a month can seem like an eternity, and it only takes missing one day of critical performance can significantly underperform an index.

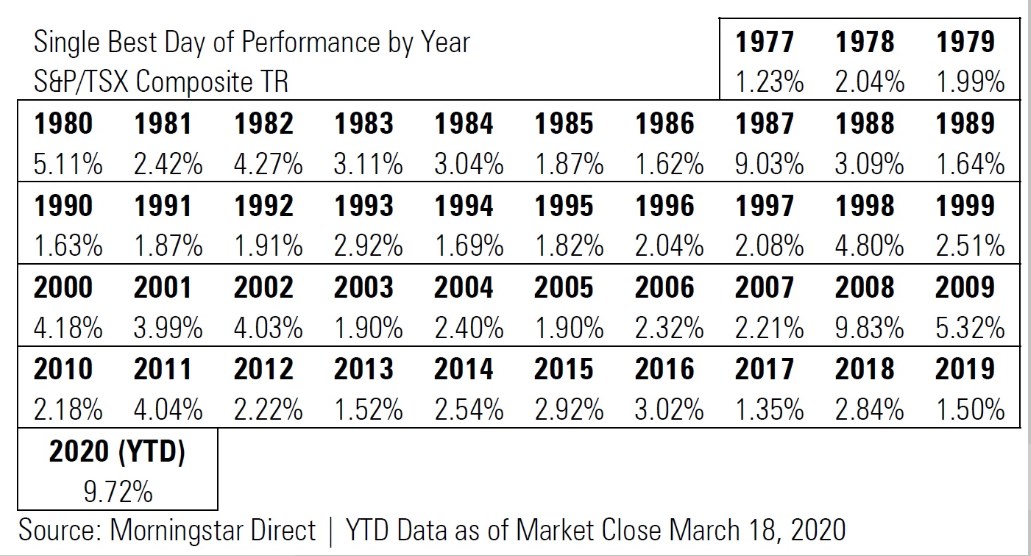

To illustrate this, I observed the daily returns of the S&P/TSX Composite Total Return index from 1977 and looked for the single best day of performance within each calendar year. I then removed the performance of that day, mimicking what would happen if you pulled your investment out for the one day and then re-invested back one day later. For reference, here is a summary of the single best days of performance of the index since the late 70’s:

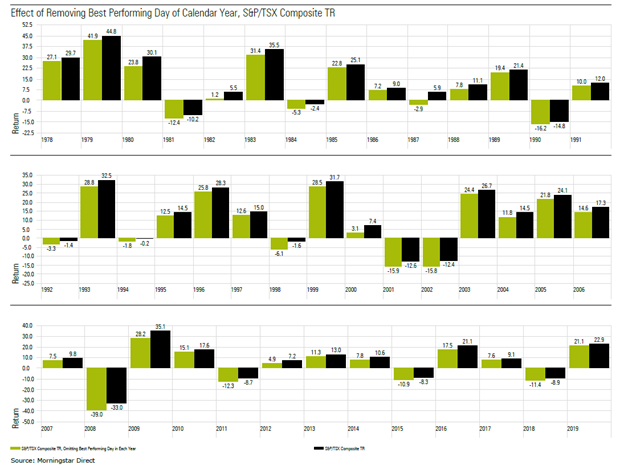

For the most part, the best day in each year ranges from one to five per cent, except for 1987 and 2008, both years where the market endured significant drawdowns. Impact-wise, here is the performance of the index in each year compared against itself sans the single best day of performance:

The point might be obvious: if you are already invested, and you happen to pull out before the best day, you’re going to lose to the index, in many cases substantially. The earlier in the year that best day happens to be, the more you will underperform largely because of daily compounding.

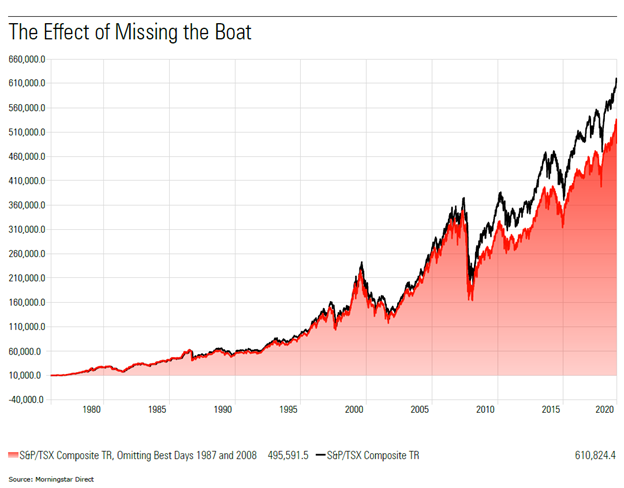

To mirror the situation that many investors are in today, I thought to run a similar analysis layering on the effect of compounding over a longer period of time, but this time assuming an investor only missed two of the best days over the last four decades: October 21st, 1987 (the day after Black Monday) and October 14th, 2008 (the day after the index lost 5.6%). These are both days that many investors may have thought to tap out, eerily similar to what some may be feeling today.

Assuming theoretical investment of $10,000 in 1977, your investment value at the peak of the market before COVID-19 would have been roughly $610,000. But if you missed the two best days in 1987 and in 2008, your portfolio would have been worth roughly $495,000. That's $115,000 (or about 19%) less than you would have made, had you been invested for those two days. That’s a significant sum for missing two days of market action - enough to put a couple of kids through undergrad.

The pain of a falling market is real, and we can all feel it. This said, the long-term pain of missing a day of investment returns won’t likely be felt until years later, especially if that day happens to be a big one. Obviously, no one knows when that day is going to occur, but the only way to ensure you catch it is to be invested.

In terms of your investment mindset, perhaps having FOMO isn’t such a bad thing right now.

This article does not constitute financial advice. It is always recommended to speak to an investment advisor or professional before investing.