Editor's note: Read the latest on how the coronavirus is rattling the markets and what you can do to navigate it.

As an investor, the sudden drop in your portfolio value is likely causing distress and panic. The panic is perhaps magnified by the 24-hour news cycle touting this as an unprecedented extreme event. Experienced investors might be quick to point out the financial crisis of 2008 or possibly Black Monday of 1987. Anecdotally we know that these extreme events happen quickly, but infrequently.

But are they actually that infrequent?

This is precisely what my colleague Dr. Paul Kaplan took concerted look at in his recent article entitled “What Prior Market Crashes Can Teach Us About Navigating the Current One” in this month’s Morningstar Magazine. While market crashes have been called black swans (a black swan being unique negative event that could not be foreseen because no similar events had occurred in the past), a careful look at historical market data actually shows that large market corrections occur on average about every six and a half years here in Canada.

Larry Siegel, Director of Research at the CFA Institute Research Foundation, coined a more appropriate term, black turkey. He defines a black turkey as “an event that is everywhere in the data—it happens all the time—but to which one is willfully blind." To understand the extent of these occurrences, Dr. Kaplan looked at the history of the S&P/TSX Composite Total Return over the last 64 years ending February 2020.

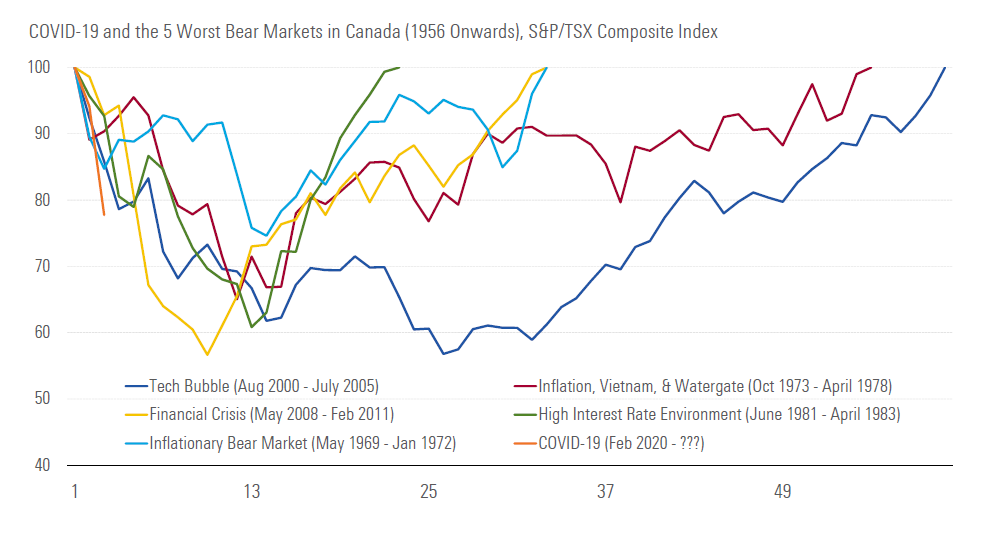

In order to define what he and Seigel call “black turkeys”, Kaplan used periods of 20% decline or more as a proxy for a black turkey (otherwise known as a bear market). On the chart above, he also plotted the highest level of cumulative wealth achieved before each of these events to help understand the extent to which investors felt the pain of said events.

Although a common measurement of pain might be to look at the maximum drawdown of an index or a fund, Kaplan opted to look at the extent of losses in tandem with the recovery period, or the amount of time it took for the index to get back up to its peak value from before a correction. By doing this, he was able to create a “Pain Index” which measure the area underneath the peak value of the index during a black turkey event and the line representing the index. As is the purpose of all indices, it gives us a reference point for comparison.

Over the last 64 years, there were ten bear markets in Canada. Though not evenly spread out, that averages out to an event every six and a half years or so. For reference, the event in the U.S. with the highest level of pain in was experienced between 1928 and 1936 known to most as the Great Depression, a period of drastically reduced global economic demand and low commodity prices. Sound familiar?

As unsettling as this data is, the key takeaways here is that markets do crash more frequently than our recency-biased minds care to remember - but they also recover.

In terms of the pain index coined by Kaplan, the event with the highest level of pain was the Tech Bubble, from which it took the index almost five years to recover, followed by the inflationary period in the early/mid 70s, and then the financial crisis. The ‘pain’ index measures the combination of how bad the crash was, but also the amount of time it took to recover. Even though the decline on the index during the financial crisis was ranked first in the table, the event ranked third in terms of pain. Time will tell where COVID-19 ranks.

In today's uncertain times it is understandably difficult to remain calm. This analysis is meant to put into perspective the fact that corrections happen more frequently than we think, and that markets inevitably correct. Those who remain disciplined and stay the course will ultimately reap the rewards that patience brings.

.jpg)