If you're a do-it-yourself investor building a portfolio, the investment options can be overwhelming. Morningstar divides the fund universe into multiple categories based on each fund's underlying holdings. But while each Morningstar Category is a little different, there's no need to add all of them--or even more than a handful--to your portfolio.

I'll explain some of the theory behind portfolio diversification by asset class and show how it can affect your portfolio. I'll also look at risk and return profiles for a model portfolio combining stocks, bonds, and a diversified asset in different weightings.

While diversification can also enhance expected returns, this piece will focus on the benefits of adding additional investments based on the potential to lower portfolio volatility. It's also worth noting that our emphasis here is on adding asset classes as opposed to funds. Depending on the type of fund you own, it might be broadly diversified or focus only on a specific asset class. This discussion will concentrate on the latter--a building-block approach where different components of the portfolio each cover a specific asset class.

Background

One of the major insights of Modern Portfolio Theory is that the risk level of a portfolio doesn't just depend on the risk profile of its individual holdings, but on whether they tend to move in the same direction, or not. This has major implications for portfolio building. If two assets are perfectly correlated (and have the same risk level), adding more assets doesn't reduce the portfolio's volatility. But if the assets have lower correlations with each other, combining them in a portfolio can lower volatility. It's one of the few cases where the whole can be more than the sum of the parts; a well-constructed portfolio can have better risk-adjusted returns than its component parts alone.

Testing the Math

Thanks to Harry Markowitz, there's a formula we can use to calculate a portfolio's expected volatility given different portfolio weightings, asset-class volatilities, and correlation levels. By plugging different values into this formula, we can test the impact of changing various variables. In a nutshell, the lower the correlation, the bigger the benefits from diversification.

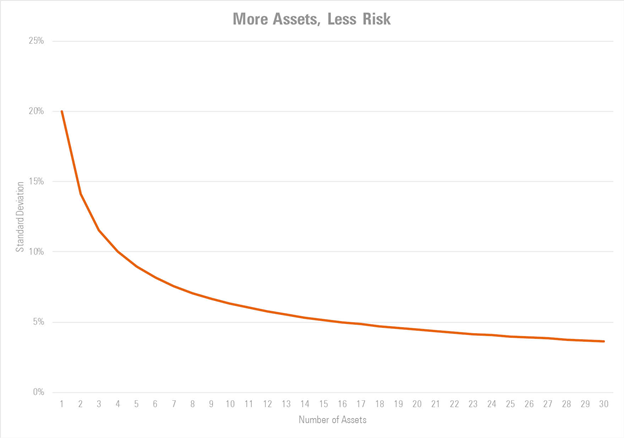

The chart below illustrates this pattern in more detail. If you can find assets with zero correlation, adding more assets to the portfolio has dramatic benefits. An increase in the number of assets to four from one leads to a 50 per cent reduction in portfolio volatility, as measured by standard deviation. The incremental benefit of adding more assets gradually declines, but it's still possible to move the needle by smaller amounts even after 20 portfolio holdings (which would imply an average position size of 5 per cent).

Source: Morningstar Direct. Data as of of May 31, 2020. Chart shows portfolio volatility by number of assets assuming a correlation coefficient of zero.

Unfortunately, it's tough to find assets with zero correlation in the real world. There are a few asset classes that can be excellent portfolio diversifiers; short-, intermediate-, and long-term government-bond funds can do a great job offsetting risk because of their negative correlations with broad market benchmarks such as the S&P 500. But nearly every other category has some amount of positive correlation with large-cap domestic equities.

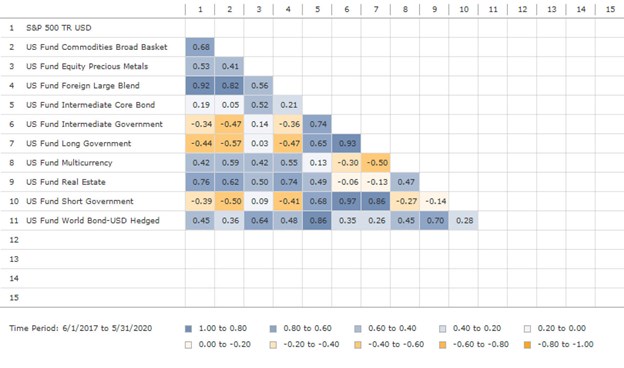

The chart below shows trailing three-year correlations for a few of the categories most often used for diversification purposes, including commodities, precious metals, multicurrency, real estate, and world-bond funds. The lowest correlation level from this group is multicurrency, with a correlation coefficient of 0.42.

Trailing 3-year correlations vs. the S&P 500

Source: Morningstar Direct. Data as of of May 31, 2020.

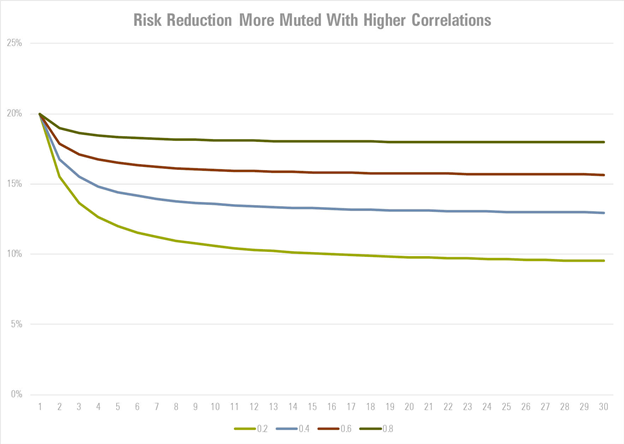

If you're adding asset classes similar to this, the benefits of diversification are more muted. As shown in the chart below, even adding 30 different assets with a correlation coefficient of 0.4 (implying an average holding size of about 3.33 per cent) would only reduce portfolio volatility by about one third. And most of those benefits come from adding the first few assets--after you get to about five or six holdings, each addition to the portfolio reduces portfolio volatility by pretty small amounts. The key lesson for portfolio building is that in most cases, adding portfolio positions that make up less than 3 per cent, 4 per cent, or even 5 per cent of assets doesn't really move the needle on your portfolio's risk profile.

Source: Morningstar Direct. Data as of of May 31, 2020. Chart shows portfolio volatility by number of assets assuming a correlation coefficient of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, or 0.8.

From theory to practice

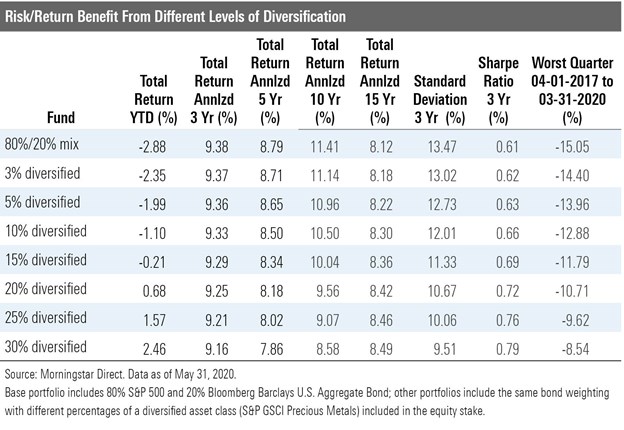

To look at this from another angle, I put together model portfolios combining assets in different weightings. As a baseline, I started with a basic portfolio of 80 per cent stocks (S&P 500) and 20 per cent bonds (Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index). Keeping the bond weighting the same, I looked at how the portfolio's risk profile would change by adding different levels of a diversified asset class (S&P GSCI Precious Metals Index). As shown in the table below, carving out 3 per cent of the portfolio for the diversified asset class reduces the portfolio's standard deviation, but only by a small amount. The 5 per cent weighting has a bit more impact, but it's not until the portfolio reaches a 10 per cent or 15 per cent weighting that we start to see the risk level and worst quarterly loss decrease in a more meaningful way.

Conclusion

The takeaway point from all of this is that scattering your portfolio too broadly across asset classes probably won't lead to better results and can even be counterproductive. It can be tempting to read about the theoretical benefits of an asset class and decide that you should add it to your portfolio for better diversification, but end up with just a tiny sliver of the new asset if you're not convinced it's the right move. (True confession: I've done this myself a few times.) It's important to note that diversification both within and across different asset classes can improve long-term returns. But if you want to diversify for risk reduction, make sure the position is big enough to count.

Morningstar associate director of manager research - quantitative research Maciej Kowara contributed to this article.