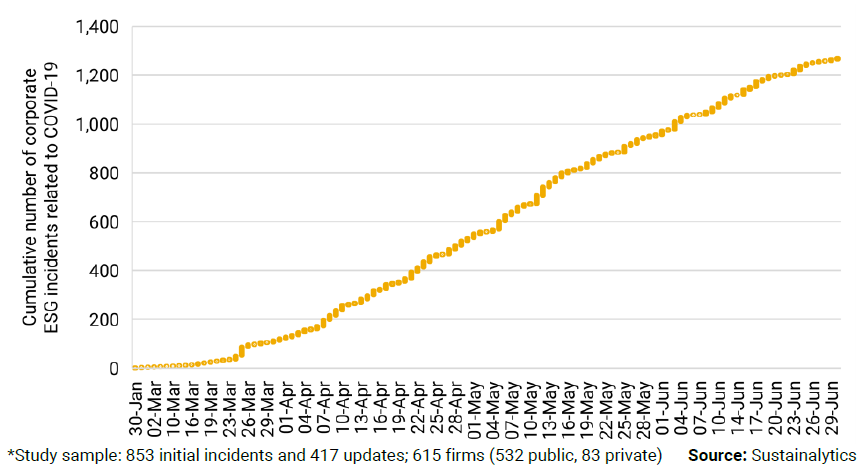

We expect the Covid-19 treatment landscape to evolve rapidly in 2020, with solid innovation supporting drug company pipelines and moats.

The dominance of Gilead’s GILD antiviral remdesivir in mid-2020 should shift to potential the wide combination use with repurposed immunology drugs (including steroid dexamethasone, which recently showed a marked survival benefit in critically ill patients) in the third quarter, emergency use of some new vaccines and targeted antibodies in the fourth quarter, and approval of several antibodies and vaccines by the end of 2020.

We expect data by the end of the year showing whether oral antiviral combinations with Pfizer’s PFE protease inhibitor or Merck’s MRK EIDD-2801 improve on remdesivir alone.

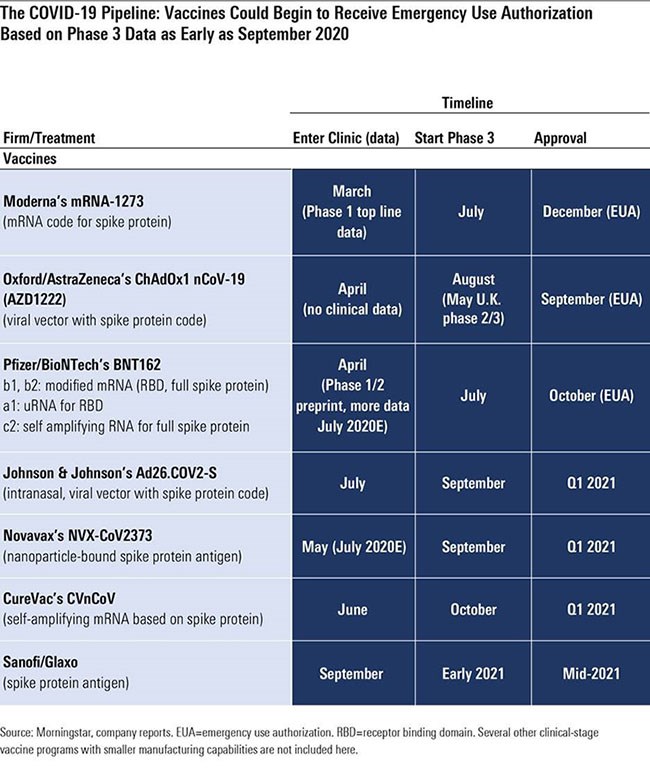

Overall, we expect multiple approved vaccines by early 2021, with wide vaccination use in developed markets by mid-2021. New vaccines are moving into trials and progressing into phase 3 more quickly than we anticipated.

Three National Institutes of Health-sponsored phase 3 trials (likely around 30,000 patients each) are poised to start soon: Moderna (MRNA) in July, AstraZeneca (AZN) in August, and Johnson & Johnson (JNJ) in September, according to a Wall Street Journal report based on conversations with NIH officials.

Pfizer and BioNTech’s (BNTX) RNA-based program could move forward on a similar schedule once the companies determine which of four potential vaccines to pursue and at what dose; initial data in July was promising, and more data is expected throughout July that could lead to a phase 3 start by the end of the month. Novavax (NVV1), which entered trials in May, brings another technology (antigen-based vaccine) to further diversify potential vaccine mechanisms, and CureVac’s mRNA vaccine entered trials in June.

Together with Merck (set to enter phase 1 this year), these programs are all likely finalists in Operation Warp Speed, a private-public partnership with US agencies, which seeks to deliver 300 million doses of a new vaccine to Americans by January 2021.

Here, we outline what we forecast for the impact of new drug development.

Time to Market for New Vaccines Still Uncertain

The length of time between phase 3 starts (where we have improving visibility) and widespread availability of a vaccine on the market is uncertain, but three vaccines look poised for potential emergency use authorisation this autumn in the United States, led by Astra/Oxford University (September), Pfizer/BioNTech (October), and Moderna (November).

Oxford has noted that if transmission is high, phase 3 results are possible in a couple of months, but if transmission drops, it could take six months. Therefore, these estimates seem reasonable assuming the companies are able to find regions with significant ongoing outbreaks, enroll trials rapidly, meet the US Food and Drug Administration threshold of 50% efficacy, and avoid unexpected safety issues or findings of enhanced disease for vaccine recipients.

Profits from new vaccines should be relatively minimal; in fact, we do not include them in our valuation models. However, we do include antiviral remdesivir (commercial supply expected in the second half of 2020) and select targeted antibodies (like Regeneron’s REGN REGN-COV2). We model sales of remdesivir peaking at $3 billion in 2021 and REGN-COV2 around $2 billion in 2021 and 2022.

• Remdesivir. Overall, we think remdesivir has a place in the near to mid-term as a treatment for patients who are hospitalised with Covid-19 but not yet on mechanical ventilation, although we expect vaccines and other treatments to reduce demand significantly beyond the next couple of years. The initial supply of remdesivir is being donated, but we expect commercial sales to begin in the second half of 2020.

• REGN-COV2. Regeneron started two clinical studies for antibody cocktail REGN-COV2 in June, focused on 1,850 hospitalised patients and 1,050 non-hospitalised patients in the US, Brazil, Mexico, and Chile. It is also conducting a prevention study with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, with 2,000 volunteers who have had close exposure to diagnosed patients in the US. However, without clinical data (or any guidance for management on initial drug pricing), it’s difficult for this program to move the meter substantially on our valuation. We assume emergency use could begin in the fall, with official approval at the end of the year. We still assume $2 billion in potential sales in 2021 and 2022, similar to our model for Gilead’s remdesivir. Several other antibody programs are entering testing, but Regeneron’s program is distinguished from most with its cocktail strategy, which in preclinical testing (data published mid-June) appears to prevent the virus from escaping the efficacy of the antibodies.

Will Covid-19 Drug Development Boost Growth?

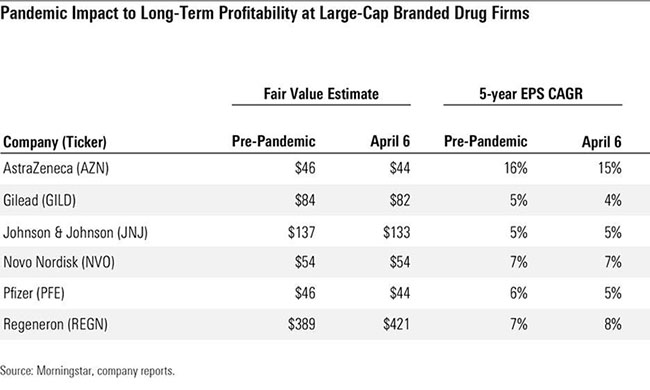

We lowered our fair value estimates by almost 2% in aggregate for Big Pharma and Big Biotech companies in early April after factoring in the economic slowdown and disruption in use of drugs, vaccines, and consumer healthcare products due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

We model near-term disruptions in drug utilisation (particularly for drugs administered in hospitals) as well as delays in clinical trials and delayed or less effective new drug launches, but highly inelastic demand for most drugs should offset most recessionary impacts and prevent any moat erosion or long-term effect on pipeline potential from the pandemic.

The Impact of Unemployment on Drug Pricing

As of the end of May, employment in the US was down by nearly 20 million jobs since February. Kaiser recently estimated that of the nearly 78 million people who lived in a family with someone who lost a job in March or April, 61% (48 million) were covered by employer-sponsored insurance before the pandemic led to job loss. Of these Americans, 27 million lost healthcare coverage as a result (unable to switch to a spouse’s insurance plan or to Medicare, for example), and 13 million are eligible for Medicaid, growing to 17 million eligible by January 2021 as unemployment insurance benefits end for most.

Newly unemployed who had previously been covered by employer-sponsored plans could begin with transitional coverage, which can last up to 18 months, or unemployment insurance. Therefore, we expect minimal impact from Medicaid switching in 2020. We expect these Americans to eventually switch to exchange plans or, if they qualify, to Medicaid, which reimburses drugs at lower prices than private plans and could pressure drug company sales.

Kaiser data (as of 2018) estimates that 49% of Americans were on employer-sponsored insurance; if all 17 million newly eligible switched to Medicaid in 2021, this could fall by 5 percentage points, to 44%. This would be significantly above the shift that drug companies witnessed during the Great Recession.

Moody’s projects annual job losses around 8 million by the end of 2020, which would be a significant improvement from end-of-May numbers and allow many to avoid the transition to Medicaid. We expect further improvement in 2021 and beyond to reduce Medicaid enrolment and the related headwind on drug sales.

Diversification is Key for Drug Companies

Assuming that the economy does not improve and we do see significant numbers of Americans enrol in Medicaid in 2021, the effect on drug companies is likely to vary significantly. The most exposed companies would be those with previously high levels of patients on employer-sponsored insurance (this is the category with the most drug pricing power to lose) and those that have a history of taking significant annual price increases (because of Medicaid’s inflation rebate rules that limit price increases).

Some older branded drugs have Medicaid rebates approaching 100%, making certain Medicaid sales minimally profitable. Insulin (Eli Lilly LLY, Novo Nordisk NVO, Sanofi SNY), immunology drugs (AbbVie’s ABBV Humira, Amgen’s AMGN Enbrel), and respiratory drugs (GlaxoSmithKline GSK) could be among the most exposed to such a shift.

We modelled Novo Nordisk as an example of a company with what we see as relatively high exposure to payer mix shift. Novo Nordisk currently gets 11% of total sales from US insulin and 28% of total sales from US GLP-1. If we assume that Novo Nordisk essentially loses all insulin sales and half of GLP-1 sales from privately insured US patients who could switch to Medicaid, this amounts to a total 1.5% impact on sales.

Glaxo and Sanofi, meanwhile, have relatively low exposure to US sales (less than a third of total sales), which should protect from payer mix risk, while Amgen and AbbVie have relatively high US exposure (more than two thirds of total sales), making the impact of Medicaid coverage changes slightly greater.

We also expect to see an impact on drug pricing outside the US due to the pandemic as budgets are broadly squeezed. Even though we already assume low-single-digit pricing pressure annually in Europe, we expect countries to increasingly work together to negotiate prices. Budgets will no doubt be tighter following Covid-19 stimulus programs, and unlike in the US, drug prices have a hard ceiling due to balanced-budget requirements.

That said, international drug pricing is already quite low relative to the US; even including an average 43% US price discount from list prices, Morningstar’s own analysis of rebates and individual analysis of net pricing of top revenue-generating drugs gets us to prices in the other developed markets that are roughly half those of US net prices.

This article first appeared on Morningstar.com