Talking about money is hard for many. Some may not have enough. Others may have made mistakes that make talking about money difficult. And others may not like to discuss finances in general. However, it is important to take away the stigma of talking about money, especially with children and young investors.

As Morningstar behavioural economics team-member Samantha Lamas points out, “The sad reality is that, in most cases, kids leave home without proper financial skills to achieve financial well-being. We see this in the endless cycle of financial mistakes in every generation.”

If you feel intimidated at the idea of discussing money with your kids, don’t worry – we’re here to help. Sarah Newcomb, senior behavioral scientist at Morningstar has a paper titled "Financial Turning Points: The Parent's Dilemma", in which she discusses some techniques that advisors and investors can use to start talking about money.

Tip 1: Start as Soon as Possible

“Dealing with money is complex,” Newcomb said. “It affects our social lives as well as our material lives, and if we don’t discuss that with children, and let them see how money really affects our lives, then the children will find out the hard way.”

No one wants their kids to find anything out the hard way, so let’s avoid that, and jump right in. To borrow lyrics from ‘The Sound of Music’, the very beginning is a very good place to start.

With children, you have a blank canvas with which to begin their relationships with money. A great way to begin talking about money is by focusing on basic concepts. Lamas points out that these foundational aspects can and should be taught at an early age, especially as there are many key concepts that don’t come naturally.

Talk About: Time as a Foundation

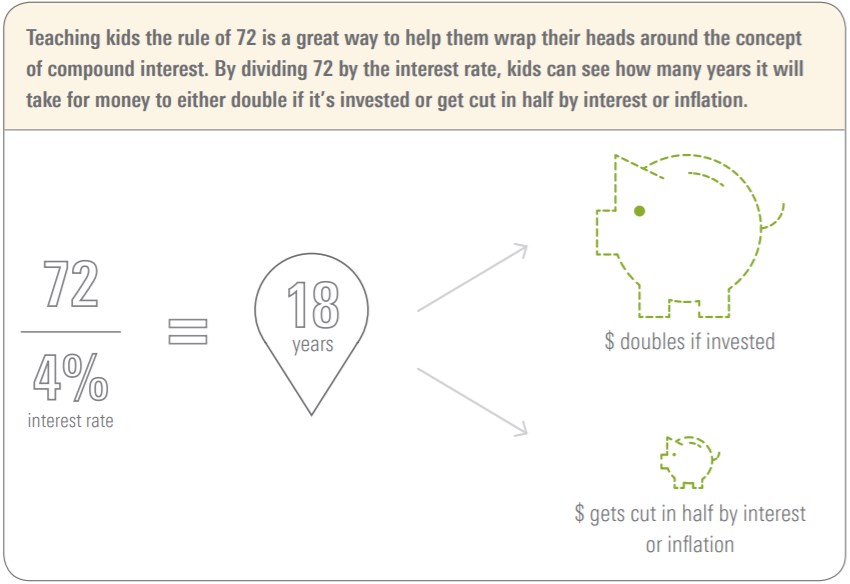

“A prime example is time perception. Our brains are simply not wired to understand and accurately calculate compound interest, which can result in huge financial mistakes. To help kids avoid these mistakes, parents can start by teaching them the rule of 72 at a young age,” Newcomb says.

What is the Rule of 72? Divide 72 by the interest rate, and that tells you how many years it will take for your money to either double if it's invested or get cut in half if you're talking about paying interest or inflation.

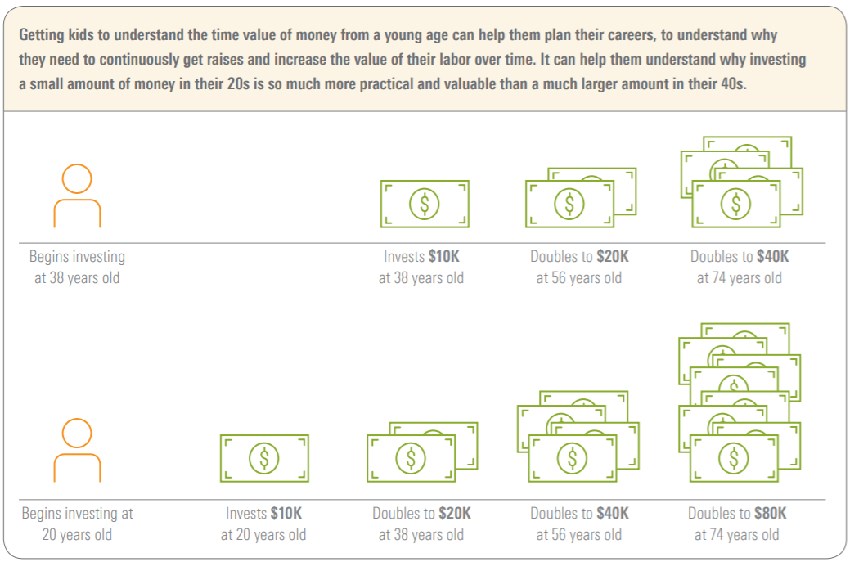

Tip 2: Simplify, Repeat, Simplify

“People can’t just teach kids something once. It must be reiterated. Teach the rule of 72 when they’re 8, and then do it again at 10, and again at 15, and again when they get a credit card. Teach the rule of 72, because it’s so simple a kid can understand,” Newcomb says, adding that “Getting kids to understand the time value of money from a young age can help them plan their careers, to understand why they need to continuously get raises and increase the value of their labour over time. It can help them understand why investing a small amount of money in their 20s is so much more practical and valuable than a much larger amount in their 40s.”

Talk About: “Superdollars”

My niblings (ages 7 and 5) love superheroes. So they pay attention when I tell them that their money can be what Karen Wallace, Morningstar’s Director of Investor Education calls, ‘Superdollars’

“It really is worthwhile to save whatever you can afford to, even if it doesn't seem like much. I think of money invested in your 20s and 30s as superdollars: with several decades to compound, this money has incredible growth potential. One dollar compounding at 6% per year will be worth $10.30 in 40 years. One dollar compounding at 6% will only be worth a third of that, $3.20, after 20 years. Put simply, the younger you are when you start investing, the more time your money has to grow and the less money you will need to save to reach your goal. By contrast, the longer you wait, the less "super" your dollars get,” she explains.

To make it even simpler, you could explain how long it would take to ‘double your money’:

Tip 3: Workshops > Lectures

Newcomb explains that people seek information about financial transactions when they need it. “When they’re buying a home, that’s when they learn about mortgages. That’s when they’ll pay the most attention, be the most receptive, and retain that information the longest because it’s personally relevant,” she explains.

You could involve your children in the process. If you’re buying a house, explain to your child what you’re doing, and why. You could also do this for a smaller purchase like a car. Or even a trip on holiday – to Disneyland!

“Those types of things can be just-in-time moments. If you keep an eye out for when their kids are having just-in-time moments, it can be really effective,” Newcomb says.

Talk About: What THEY Want

Lamas also suggests using the child’s own desires as teaching moments. “When your child wants to redecorate her bedroom, give her a budget, and have her shop for the things herself. It will be a powerful lesson in bargain hunting when she is personally invested in the result,” she says.

Tip 4: Pros vs. Cons

Back in 2013, Morningstar’s Director of Personal Finance Christine Benz asked Morningstar.com readers for tips on how to discuss money with children. One of the tips was for parents to discuss spending choices with their children, especially when it came to the children’s own purchases. For example, explaining to their children that just because you COULD afford something, it did not mean that you SHOULD buy it.

Talk About: The Value of Delayed Gratification

The best way to do this is by asking smart questions. Some of the crowdsourced questions included:

- How much does it cost?

- Is it on sale or cheaper at another store?

- Do you have that much money?

- Are you sure you want to spend the money now?

- Would you rather put it on your birthday/festival list?

Tip 5: Buckets for Kids

Benz is a fan of the ‘Bucket Approach to retirement’ where retirement portfolios are segmented by time horizons. Bucket 1 is with a very short-term horizon, Bucket 2 with an intermediate-term horizon, while Bucket 3 is to hold long-term investments. But a Morningstar.com reader suggested that the bucket system might work for children as well.

Talk About: Segmentation

The reader gave his children four piggy banks – or buckets. One each for 1) Spending 2) Saving 3) Investing 4) Charity. He explained the concept of each of them, and then, whenever the children received money, they could choose which piggy bank, or bucket, their asset went.

The Bottom Line

There's no teacher like experience.

“Although it may feel uncomfortable to do so, bringing kids into financial decisions early on gives them the experience and confidence they will need later on in life to handle their own finances. Giving them a 'safe place to fail' when they are younger can save them years of anxiety later in life,” points out Newcomb.