Diversification is often called the only free lunch in investing. A portfolio made up of building blocks capable of moving in different directions can have better risk-adjusted returns than its component parts. Allocating to different asset classes can also minimize pain during market crashes.

Consider the first quarter of 2020. As COVID-19 became a pandemic, equity markets entered a synchronized nosedive—from Toronto to New York, London to Shanghai, Sydney to Sao Paulo, and points between. Canadian stocks lost more than 20% in the first quarter of 2020; the U.S. market fell a similar amount in U.S. dollar terms. Developed-market equities outside North America shed 15% of their value, and emerging-market stocks declined 17% (both in Canadian dollar terms). It was the fastest decline since the Great Depression.

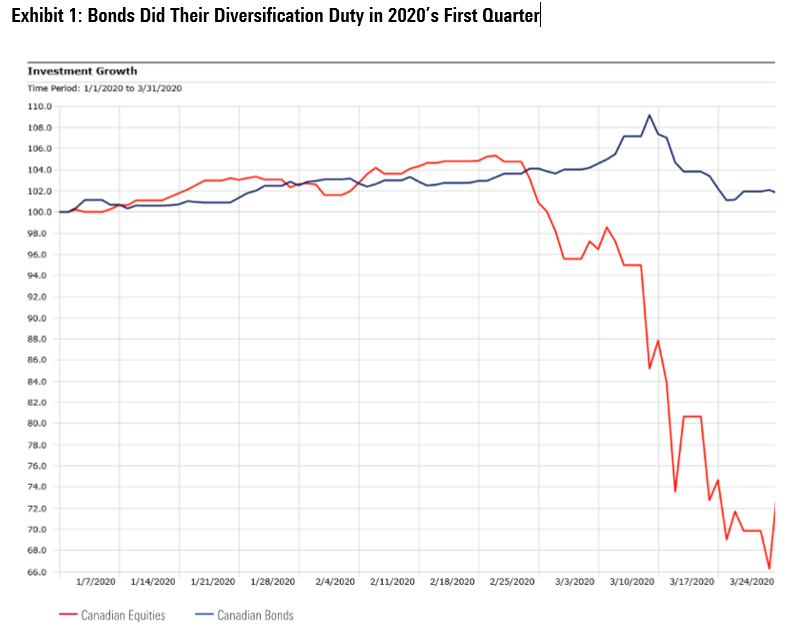

While equity market correlations were going to 1 in a crisis, as the saying goes, bonds provided real diversification benefit. Consider the behavior of Morningstar indexes focused on Canadian stocks and Canadian bonds during the pandemic-driven bear market of 2020’s first quarter.

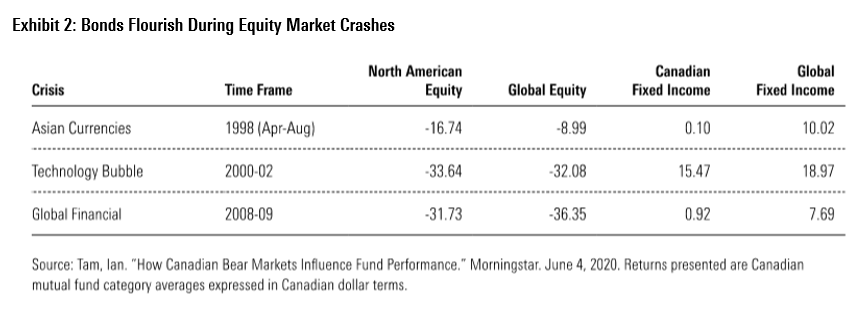

The pattern of bonds holding up during a crisis is consistent with a long-running trend. In a study of asset class behaviour during bear markets, Ian Tam, Morningstar Canada's director of investment research, examined a series of equity market crashes over the past 25 years using Morningstar mutual fund category averages. As displayed in Exhibit 2, Tam observed that Canadian fixed income and global fixed income were incredibly resilient as stocks were selling off, often gaining significant ground in flights to safety.

What About Equities?

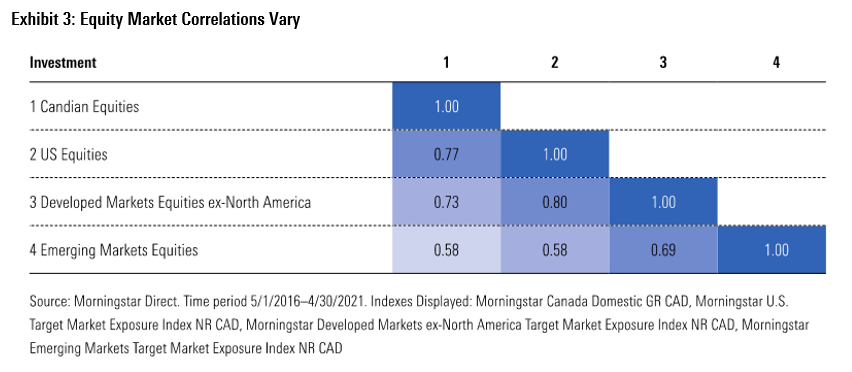

Equities across geographies are more correlated to each other than stocks are to bonds. Several factors help explain this, from the influence of global capital flows to the interconnectedness of the global economy. For example, less than half the revenue of the Canadian equity market is actually sourced from Canada, according to Morningstar estimates.

Then there are sector dynamics. Energy and basic materials are deeply influenced by global commodities prices. Canada's Barrick Gold (ABX), South Africa's AngloGold Ashanti (ANG), and the United States' Newmont (NEM) will all move together, while oil prices will affect Canadian Natural Resources (CNQ), Australia's Woodside Petroleum (WPL), and Saudi Aramco similarly. Technology companies across geographies benefited from the shift to working and shopping from home during the pandemic.

In Exhibit 3, it's not surprising to see global equity markets positively correlated. Canada and the U.S. are the most similar and emerging-market equities the most different.

But just because equities in different geographies don't diverge to the same extent as stocks and bonds doesn't mean they don't make essential contributions to a diversified portfolio. Canadian investors, like their counterparts everywhere, tend to exhibit home country bias, where preference for the familiar local market can leave them overexposed to Canadian equity and fixed-income assets.

Some home country bias can be justified on the basis of currency. When investors purchase an asset outside their home market, they take on currency risk. If the Canadian dollar appreciates against the U.S. dollar, the euro, or the yen, and so on, assets purchased in foreign currency will be worth less when converted. Hedging is an option, but an investor who earns and spends in Canadian dollars and plans to retire in Canada can be forgiven for wanting to minimize currency risk.

On the other hand, currency risk can also be viewed as currency diversification. When the Canadian dollar weakens, foreign assets are worth more to an unhedged Canadian investor. For example, the Canadian dollar's steep decline against the U.S. dollar between 2011 and 2015 amplified the gains of U.S. equities from an unhedged Canadian investor perspective.

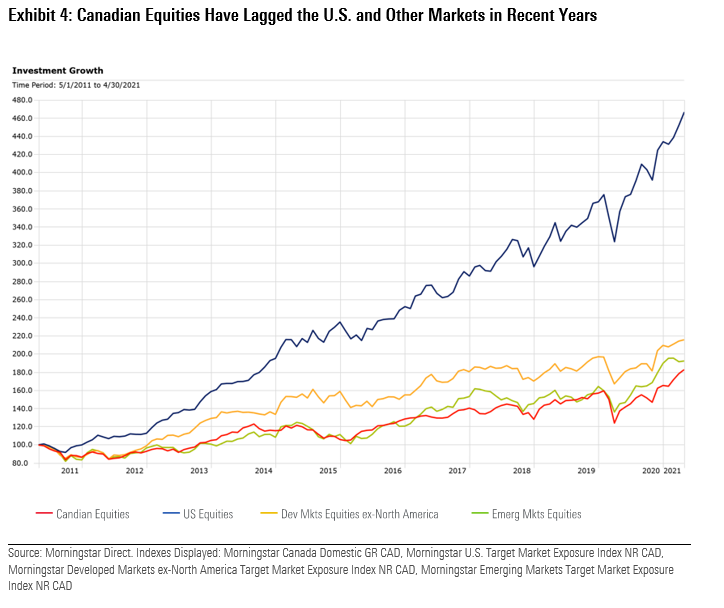

As displayed in Exhibit 4, Canadian investors with significant home country bias missed out on substantial global equity market gains over the past 10 years, especially south of the border.

Market leadership could certainly look different in the future. But regardless of one's outlook, there are several structural reasons to diversify globally. Canadian equities represent less than 3% of global market capitalization as of April 30, 2021. That compares with nearly 57% market share for U.S. stocks, roughly 27% for developed-market stocks outside North America (Japan and the United Kingdom as two largest contributors), and roughly 13% for emerging-market equities. A Canadian equity investor with significant home country bias has a portfolio that does not reflect the global opportunity set.

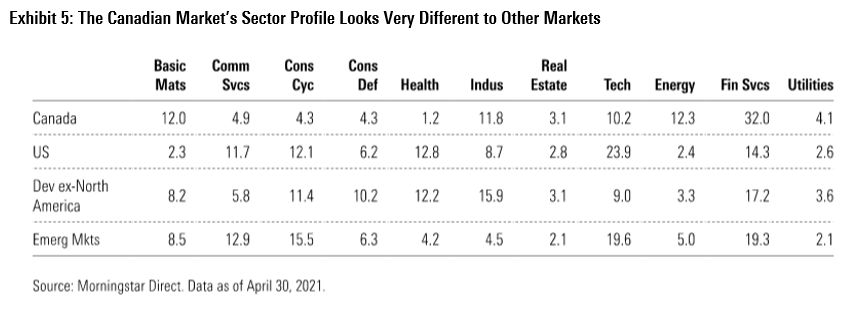

Also, consider sector weights. As displayed in Exhibit 5, the Canadian market has almost no exposure to healthcare stocks and far less technology representation than the U.S., with its FAANG stocks, or emerging markets, which contain the Chinese technology giants and the likes of Samsung in Korea. Meanwhile, Canadian investors are overexposed to energy and basic materials relative to the global equities universe.

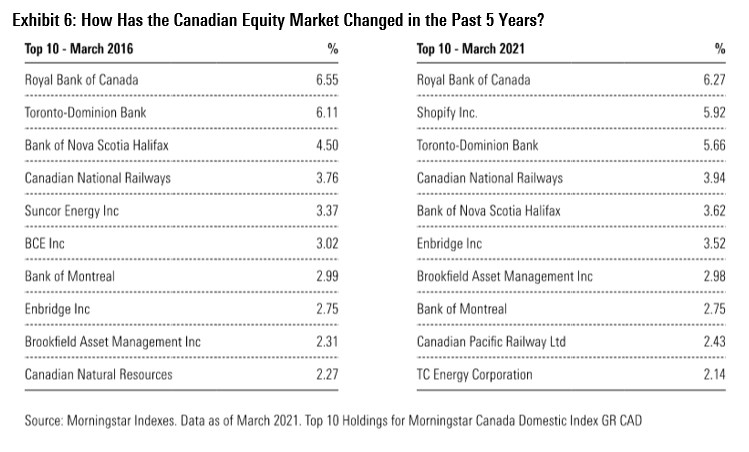

It's also key to look at how the Canadian equity market has evolved in recent years. The market has become more concentrated, with the top 10 constituents accounting for roughly 40% of the market. That compares with 26% in the U.S., which is also more top heavy than before. Unsurprisingly, given this concentration, Morningstar's Canadian equity index has been more volatile over the past decade—measured by standard deviation of returns—than benchmarks measuring the U.S., developed markets outside North America, and even emerging-market equities. As displayed in Exhibit 9, the most notable change to the Canadian market over the past 10 years is the remarkable rise of Shopify.

Shopify joins companies like Facebook and Tesla that have gone from small players five years ago to among the largest companies in their home markets, and similarly for Chinese technology phenoms Alibaba, Baidu, and JD.com. From its IPO in 2015, the Canadian e-commerce platform operator is now the second-largest public company in its market, larger than Bank of Montreal, which traces its history back to 1817. Shopify hopes to enjoy the staying power of BMO, and avoid the fate of previous Canadian technology darlings like Nortel Networks, which accounted for more than one third of the Canadian equity market during the tech, telecom, and media bubble of the late 1990s before becoming the largest bankruptcy in Canadian history in 2009, or Research in Motion, which was the country's largest public company in 2008, when its BlackBerry device owned roughly 20% of the global smartphone market, but is a much smaller player today.

Meanwhile, Canada's big banks have become an even larger share of the Canadian equity market in recent years. The banks benefit from many competitive advantages including high barriers to entry, switching costs, and regulation. Yet, their outsize share of the Canadian equity market increases the need for investors to diversify. The banks are all exposed to the Canadian economy and housing market. While it's hard to imagine threats to their entrenched positions, disruption could materialize, whether digital or regulatory. Australia, another market dominated by a small number of domestic banks, saw its banks shaken by a Royal Commission review.

Don’t Turn Down a Free Lunch

It's said that in a crisis, correlations go to 1. This reflects the tendency of panicking investors to act indiscriminately, pushing asset prices down across the board. In the first quarter of 2020, equity markets across the globe fell in synchronized fashion, but high-quality bonds held up just fine. Investors diversified across asset class appreciated the fact that some of their assets were zigging while others were zagging.

Meanwhile, Canadian investors diversified across global equity markets would have achieved higher returns in recent years than with an all-domestic portfolio. While changing conditions might diminish the appeal of bonds or global equities, a strategic asset allocation helps protect investors from unexpected events. The pandemic showed that black swans can appear unexpectedly.