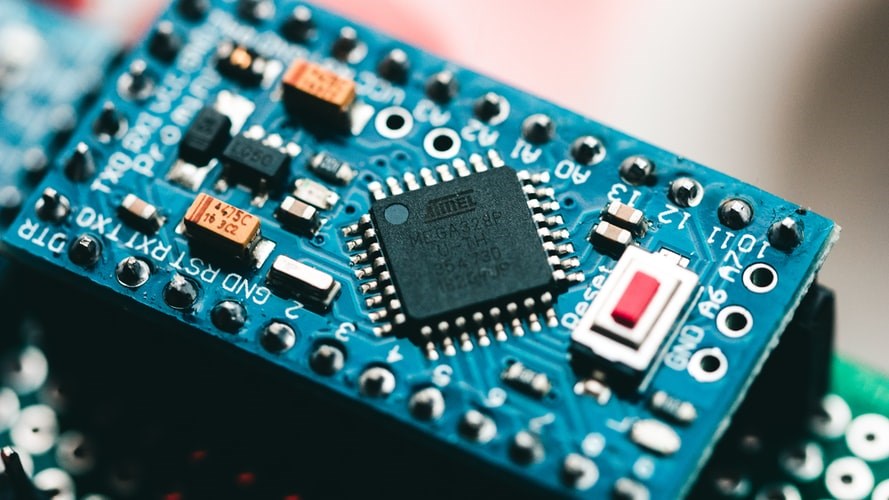

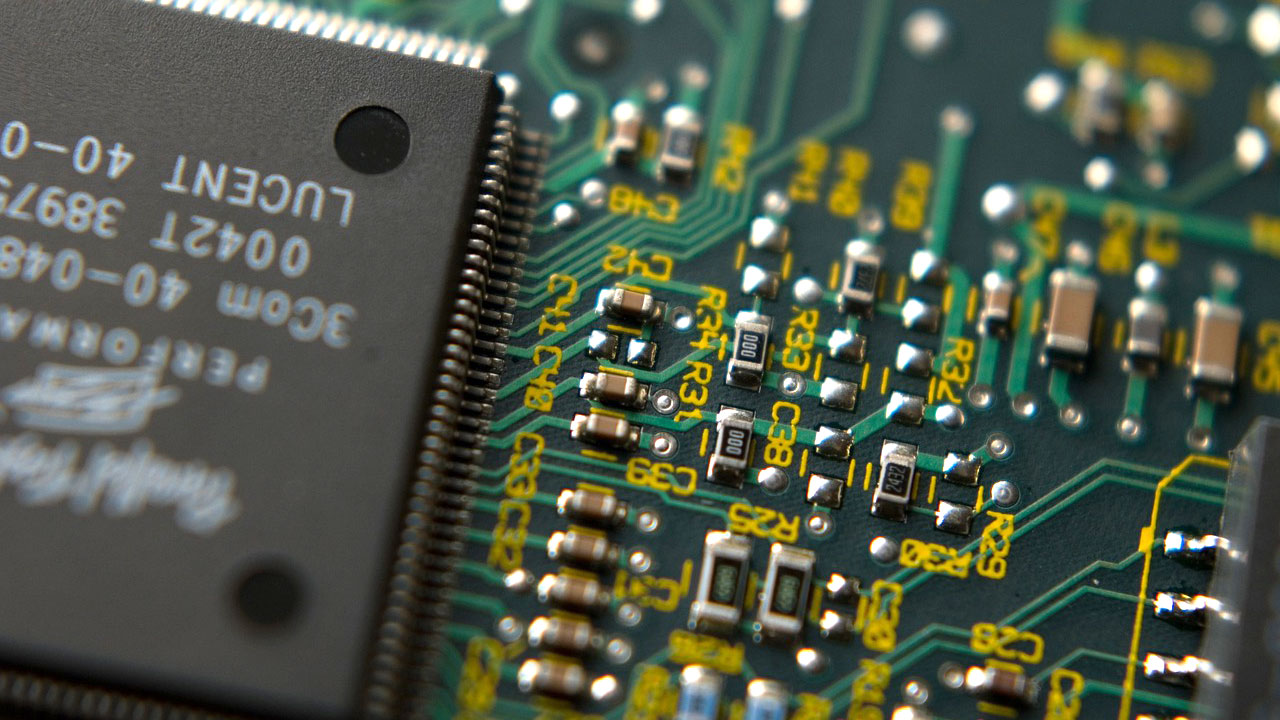

The coronavirus pandemic disrupted (and continues to disrupt) lives across the world. And one of the key ways in which this is visible hinges on the global shortage of semiconductor chips, the processors that go into our computers, game consoles, WiFi routers, and electric vehicles (EVs) – especially EVs.

In fact, car manufacturing has been the hardest hit by the shortage. “Carmakers are shutting down production because they are unable to redesign electronics with alternative parts quickly enough, while unwilling to put lesser chips inside their vehicles,” reports a Morningstar study, which expects the shortage in that industry to last up to early 2022. For example, at the end of April, General Motors announced that it would suspend or reduce production at three plants that had previously been spared the undersupply of chips.

Until now, new car prices have been relatively unscathed by the shortage, even though car inventories are reduced by half. Unexpectedly, it is the used car market that is taking the crunch. “People seem to have decided not to use the public transit,” says Jocelyn Paquet, economist at National Bank of Canada. At the end of May, year-over-year, used cars and trucks prices have shot up by 29.7% in the United States. Abhinav Davuluri, Technology Equity Strategist at Morningstar, adds that “A lot of what we see in the U.S. can be translated to Canada.”

Mind you, notes Paquet, this price inflation is not only the consequence of the chip shortage.

Why the Shortage?

Many factors have combined to cause the shortage of chips. Globally, everything started with the U.S.-China trade war and escalated with the pandemic. “China feared sanctions, so it stockpiled,” explains Angelo Katsoras, geopolitical analyst at National Bank of Canada. It didn’t stop there. “Everybody started to hoard because no one trusted that their neighbour was not also hoarding.”

This mistrust spilled over into the global supply network. “Just-in-time management requires high confidence, and that confidence is now shaken,” Katsoras adds.

In the car industry, explains the Morningstar report, when the pandemic hit, manufacturers decided to cancel chip orders with their suppliers. But when car sales picked up earlier than expected, they tried to renew their contracts, without success, as suppliers had moved on to other clients.

Now, there is more than mistrust at work: having suffered from acute supply shortages, industrial players are reconfiguring their supply chains and bringing them closer to home. “An increase in shipping costs and shortages of key manufacturing inputs have reminded us of the vulnerabilities of relying too much on efficient rather than resilient supply chains,” writes Sohaib Shahid, senior economist at TD Economics.

Add to the shortage the fact that chip consumption is exploding with all the “smart” everything happening everywhere: smart-phones, smart-cars, smart-appliances, notwithstanding the rising demand from cloud computing, AI and the Internet-of-things. That’s why chip sales jumped from 73 billion units in January 2020, before the pandemic, to 100 million at the end of April, according to the World Semiconductor Trade Statistics.

Where there was only one global chip supply chain, “we are now building two,” says Katsoras, notably because the U.S. suddenly realized that while they sell more than 50% of the world’s microprocessors, they are manufacturing only 12%. So TSMC, the world’s largest chip manufacturer, is building two new chip plants in the U.S. – and two more in China. At the same time, the U.S. government has passed the CHIPS act in early June, with a budget of US$ 52 billion to assist chip building capacity in the country. In a similar vein, “the EU is aiming to produce 20% of the global supply of semiconductors by 2030,” reports ZDNet.

All this new capacity, “will take a few years to come online,” notes Katsoras. And this means that the chip shortage could be with us for a while, at least into the middle of 2022.

iPhone Price Tag

What does this mean for the price of the next iPhone or gaming station? Though there haven’t been any major price rises yet, this could change. Plus, since “smart” now extends well beyond phones, chip price inflation is reaching well beyond electronic devices. Appliance maker Whirlpool was phasing in price increases of between 5%-12% to the end of last June, reports Shahid. “Meanwhile, he adds, American conglomerate Proctor & Gamble has said that price increases will range from mid to high digit percentages and will go into effect in mid-September.”

For the time being, manufacturers are reluctant to hike prices, “and that is in part making the shortage more acute,” explains Paquet. “Their reluctance hinges on 20 years of tame inflation where they rarely had to adjust prices rapidly. For the time being, they prefer to bear higher costs, fearing a negative reaction from consumers. But we expect that at some point they will push prices up.” Shahid expects the same: “The longer these disruptions last, the higher the likelihood that businesses pass on the rising costs to consumers.”

In Canada, “we are starting to see an impact, but it seems limited to the car manufacturing sector, imports and exports being both affected,” says Paquet. But he expects the same U.S. consumer price effects to take hold here for the very simple reason that Canada manufactures neither iPhones nor printers nor game consoles, and very little home appliances.

For, as global supply chains and production capacities reshuffle, Canada could suffer somewhat. “We could expect China, the U.S. and Europe to favour their own markets, states Katsoras, while Canada becomes of secondary importance."

.jpg)