Last quarter, in less than two months, the Canadian dollar lost nearly 10 cents in value. In June 2021, the loonie held a relatively strong position at US$1.20, but in August, it had weakened to US$1.29.

“A funny creature, the loonie,” says National Bank economist Kyle Dahms. It is rare to see major currencies like the U.S. dollar, the euro or the yen lose nearly 10% of their value within a few weeks. Aidan Garrib, head of global macro strategy and research at Pavilion Global Market points out that it sometimes happens to second-tier currencies of countries heavy in commodities, like Australia, or of emerging markets, like Mexico.

Domestic Factors Seem Strong

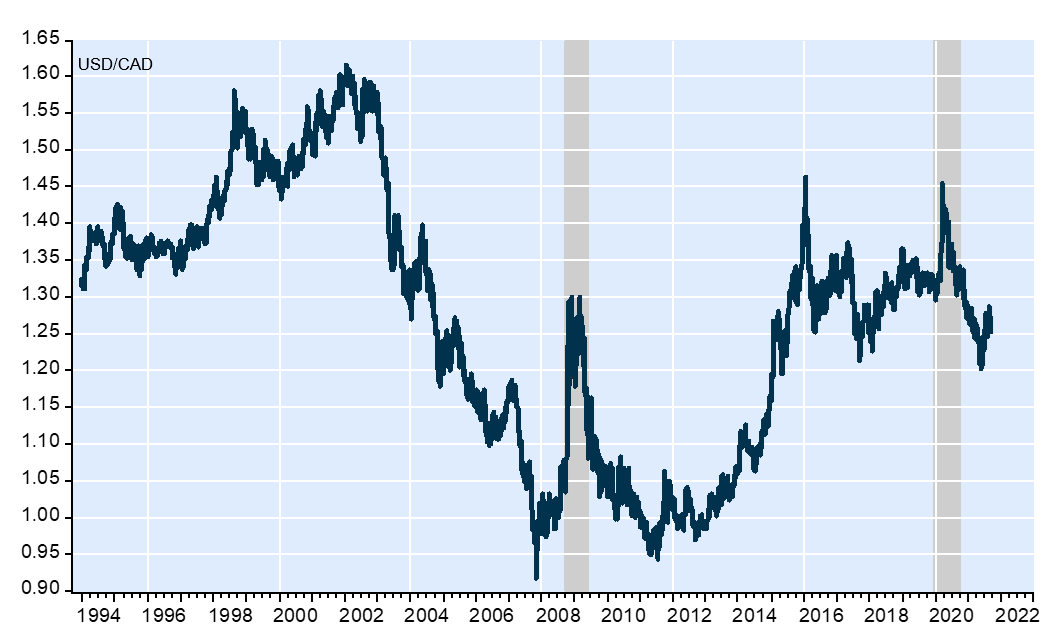

Exhibit 1: U.S. Dollar Vs Canadian Dollar

Source: National Bank (With data from Refinitiv)

Looking at a chart tracing the historical performance of USD/CAD since 1993, such a rapid fall happened twice before, in 2016 and in March-April 2020. Before that, the loonie went from a low of US$1.60 to a high of US$0.92, but that happened over a seven-year period from 2001 to 2008. From 2012 to 2016, the Canadian dollar took another US$ 0.50 dive.

This time around, the steep fall in lumber prices in the third quarter is considered the main culprit of the loonie’s woes. Dahms disagrees. “One needs to keep in mind that forest products represent only 11% of all commodities (in Canada), which is the smallest share of the four main categories forming the Bank of Canada’s commodity price index,” he points out. Those other categories are all rising, notably agricultural commodities reached a record growth level of 17%, and metals are also near record highs at 24%. That largely compensates the fall in lumber prices.

What about oil? In the 6-week period when the loonie dipped this last summer, the Canadian Crude Index reached a new high of $60. Since then, it has strengthened to $68.

“Canada posted a current account surplus for the second consecutive quarter in Q2 2021,” reaching $3.6 billion during the quarter, writes Stéfane Marion, chief economist and strategist at Banque Nationale. Trying to explain why the CAD remains so weak in spite of this, he finds the reason in “the temporary nature of the surplus”. While Canada is a net exporter of travelers and their expenses, “for the first time, our country is experiencing travel surpluses. (...) A return to pre-crisis levels could reduce the current account surplus by as much as $4-5 billion.”

Dahms points to other strong points of the Canadian economy: job creation is vigorous and COVID-19 exerts diminished pressure on the economy and on health systems. One key factor can explain the loonie’s weakness: a negative contraction of 1.1% in Canada’s real GDP during Q2, which was below expectations of a 2.5% positive growth. Nevertheless, Dahms points out, nominal GDP remains strong at a projected annualized rate of 7%, and Canada’s economic recovery remains positive, trailing the one in the U.S. by only two percentage points.

Is America the Cause?

Since domestic indicators seem to be strong, can the reason be found outside our borders? Perhaps in the U.S., to which Canada’s exports total US$ 270 billion, 12 times the size of its exports to its second largest export partner, China? “As U.S. industrial production has picked up, Canadian exports have surged to new heights, but that trading activity has weakened lately, pulling the loonie down”, Garrib says.

One also has to focus on what’s happening to the U.S. dollar. “More uncertain economic conditions have undermined risk appetite and increased the interest of investors for the American dollar,” claims Dahms. The USD broad index has already gained 3% compared to its lowest level in June, and economic surprises have turned negative in the U.S. as well as in China. “The USD hike has been exacerbated by speculators that have become positive on the greenback for the first time since early 2020,” he says.

It’s seems like it’s less about the weakening of the Canadian dollar, than the rise of the U.S. dollar.

FX Swaps Could Be to Blame

According to the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) in its most recent foreign exchange survey, currency transactions averaged US$ 6.5 trillion a day in 2019. Banks, large and small, account for a large majority of transactions. The spot market (currency versus currency exchanges) represents a share of about 30%, while foreign currency swaps and forwards account for about 65%. A foreign currency swap, or FX swap, is when two foreign parties agree to exchange currency simultaneously.

The activity in FX swaps, the majority of which have less than one-week durations, is carried out “for banks’ own treasury unit for funding or on behalf of clients for funding and hedging purposes”, indicates the Review. Speculation accounts for about 13% of all transactions, carried out mostly by hedge funds who try to take advantage of market inefficiencies introduced by “naive” players (corporate treasurers and investment funds) that try to cover their market risks, according to Dori Levanoni, chief investment strategist at First Quadrant.

So when a Canadian company wonders why its profit on an international sale has suddenly increased or shrunk by 10% because of wild jumps in the loonie, it many make sense to investigate the prevailing view of FX swappers, rather than the rates of oil, or lumber or central banks.

Currency Risk and You

While most investors do not actively trade in currencies, many of us might have exposure to currency risk through our mutual fund or ETF holdings. Back in 2010, Morningstar Senior manager research analyst Gregg Wolper explained currency risk. “Currency strategies can be complex. In the prospectus sense, however, currency risk is straightforward: It means that currencies rise and fall over time. If you own securities denominated in foreign currencies, when those currencies lose value versus the U.S. dollar, you'll get lower returns from the securities than if the currency values had stayed flat or risen,” he writes.

From the Individual Investor's Perspective, Wolper explains that it's important to understand the impact of owning foreign currencies – directly or through a fund. “Take care when considering such investments, though. Trying to time currency movements is a tricky game, often foiling even those who spend all their time studying such things. There's a reason so many smart international managers don't even attempt to make currency guesses, or do so sparingly,” he warns.