Change is slow but inevitable.

Over the past few years, we’ve been covering the proxy season both in Canada and the United States, examining issues like the investor pushback on Canadian banks funding fossil fuels, the dual share class structure drowning out the voice of investors, questioning who has the power in the proxy-voting process, or even examining how asset managers speak versus how they vote on environmental, social, and governance issues.

The shareholder proposals and underlying issues we’ve covered have mostly highlighted the advocacy efforts of sustainability-minded investors. The proposals they file at companies have been made in an earnest effort to secure long-term value for investors and other stakeholders, whether one shares the views of the proxies’ authors or not. Recently, though, we’ve seen an increase in what we’ve been calling ‘anti-ESG’ proposals. These are disingenuously submitted proposals, usually by groups that oppose the work of ‘pro-ESG’ investors.

Through conversations with multiple industry players, many on background, we get the sense that the intent behind some of these proposals is less to offer a constructive path to change and more to disrupt a movement that is gaining steam. The aim appears to be to hinder the work that pro-ESG groups are doing, by using the machinery of proxies against it and thereby negating the efficacy of legitimate pro-ESG proposals.

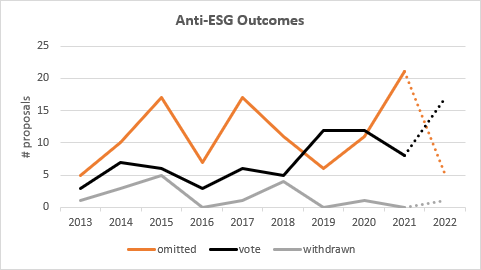

Morningstar’s Jackie Cook points out that while these resolutions comprise only a small proportion of ESG issues that come to vote, they potentially contribute noise to analyses of ESG voting, and for this reason, Morningstar’s proxy database tags the resolution filer and flags ‘anti-ESG’ resolutions. Cook is director of stewardship in the Sustainalytics' Stewardship Services Team, managing the ESG Voting Policy Overlay service.

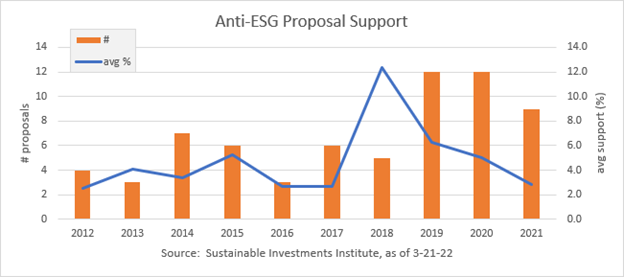

We also found that companies, and investors, are fighting back. In some cases, pro-ESG groups are changing their strategies and approaches to counter the tactics being used by anti-ESG players. In others, when anti-ESG proposals come up for vote at company meetings, investors are rejecting them, with many earning 3% or less support. This, too, comes with some danger, though, because if any proposal does not get a minimum of 5% support from investors, under the new regulatory rules in the U.S., that proposal cannot be filed again for three years, regardless of intent. Here is what we found.

Section 1: What’s Happening

In the middle of March, As You Sow, the Sustainable Investment Institute (Si2), and Proxy Impact released the Proxy Preview 2022, a forecast of the upcoming proxy-voting season. (Find out what proxy voting is here.)

The report examined 529 shareholder resolutions on ESG-related issues, of which the authors anticipate that more than 300 could see votes at annual general meetings in this proxy season.

Filings are up 20% compared with a year ago. As of the writing of the report, shareholders earned five majority votes – two at Apple (AAPL) on racial justice and concealment clause risks, one at Costco Wholesale (COST) on greenhouse gas reduction targets, one at Jack in the Box (JACK) on plastic packaging – which earned 95.4% of the vote – and one at Walt Disney (DIS) on gender and minority pay disparity.

While this is encouraging, experts in the field have noticed an increase in ‘anti-ESG’ filings as well.

What Are the Anti-ESG Proposals?

"The field of proposals from politically conservative groups, chief among them the National Center for Public Policy Research (NCPPR), continues to focus heavily on social policy. It is joined this year by the National Legal and Policy Center (NLPC). Resolutions from these and similarly minded proponents seek action that is the mirror image of what all the other proposals request, aside from doing business in China,” the report notes.

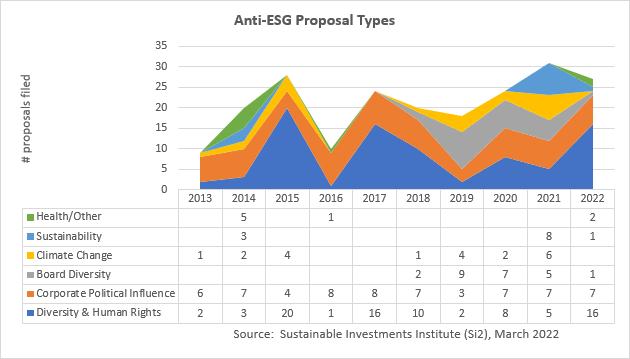

At least 27 such proposals had been filed by the middle of March, evenly split between diversity (nine), corporate political influence and charitable giving (nine), and human rights (eight).

Heidi Welsh, the founding executive director of the Sustainable Investment Institute and co-author of the Proxy Preview 2022 report, believes that it is likely that this number increases based on the actual filed proxy statements.

Jamie Bonham, director of corporate engagement at NEI Investments, agrees. “We have definitely noticed the increase in anti-ESG filing for a while now, where the intent is that the group that doesn't really believe in ESG wants companies to roll back ESG-related initiatives,” he said. “There are a few more of them now than there used to be,” he adds.

Anti-ESG Issues Being Raised

Issues include ideological diversity of the boards, lobbying, charitable donations, and, more recently, issues around racial justice.

“It is clear to me that these are not investment approaches, rather, they are political calls being used to undermine the ESG-focused filings and proposals. A quick look at the NCPPR website shows their explicit aim is to give voice to “free-market” viewpoints, although there’s little evidence that many investors in the capital markets today support these views, if one looks at where shareholder votes are trending. Facts on the ground show clear and increasing support for more corporate disclosure about diversity, climate change, and corporate political influence,” Welsh says.

Regardless of the implicit or explicit intent, the outcomes don’t always work in the favour of the filing group. “It is gratifying to see that companies have been pushing back. We have seen companies saying this is what we will embrace, this is what will make us stronger, this is good for company stakeholders, and so we have seen push back on the anti-ESG sentiment,” Bonham says.

Section 2: The Tactics Being Used

How Anti-ESG Shareholder Proposals Work

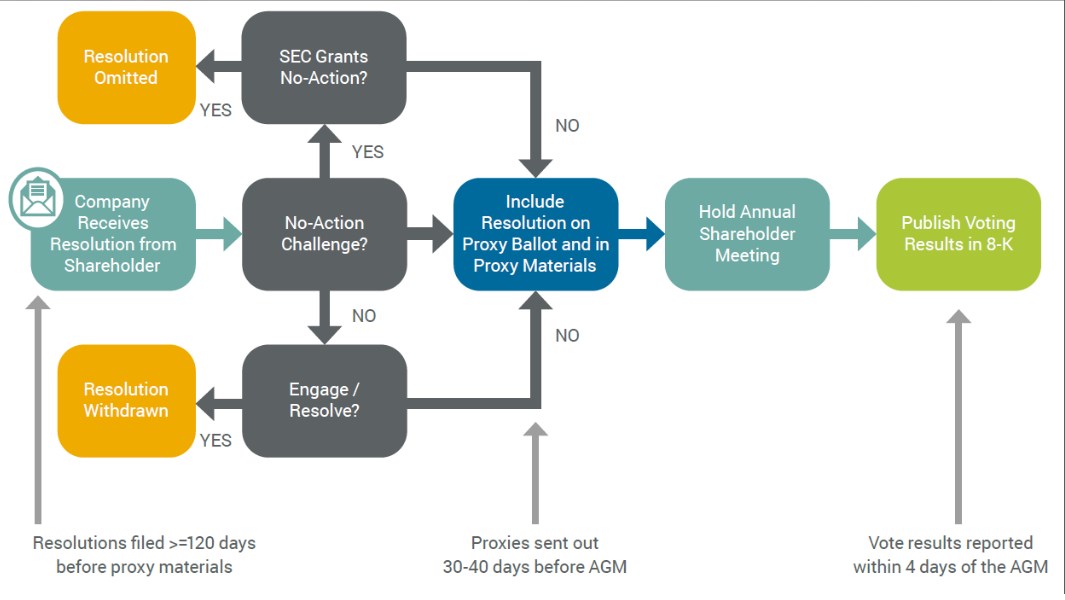

In order for a shareholder proposal to get in front of investors and be eligible for a vote, the resolution must be accepted and put on the company’s annual general meeting agenda. If the company wants, it can challenge the proposal with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, and the proposal must then pass through the SEC process – which is no walk in the park.

“If a company feels that a resolution should be excluded from the ballot, it can request ‘no-action’ relief from the SEC’s Division of Corporate Finance. If the SEC concurs, the resolution can be omitted. If not, it goes to investors for a vote,” explains Cook. Here is what the process looks like.

As Bonham points out, the SEC decides outcomes based on various precedents. That means that if a proposal has been cleared in the past, it is more likely to be cleared in the future. And so, after failing to make it past the SEC for a few years, a lot of the anti-ESG proposals found language and phrasing that the commission finds acceptable – by copying earlier approved pro-ESG proposals.

“Proposals filed by anti-ESG players can be characterized in two ways – original filings and those that have been duplicated based on previously filed proposals. It is important to understand that original filings have little to no investor support. The issue gets a bit murkier when investors are faced with filings that mirror those passed or presented in previous years,” Welsh says.

At this point, it would help to understand how a proposal is structured. As the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility explains, proposals are roughly one page in length and contain a specific request or "ask" – the “RESOLVED” clause, along with a number of carefully researched rationales in the form of "WHEREAS" clauses, or supporting statements.

In the case of many anti-ESG proposals, Welsh says, the “RESOLVED” clause is virtually identical to previously filed proposals, while the summary statement diverges significantly.

“This tactic started with votes around lobbying and election spending, but has since encompassed votes around racial justice, audits and diversity, as well as some environmental-related proposals,” she adds.

In the years where support rose, the filed proposals copied pro-ESG proposals. Examples include Duke Energy’s (DUK) and General Electric’s (GE) 2018 proposals on the benefits of lobbying and the same proposals at Eli Lilly (LLY) and Pfizer (PFE) in 2019.

NEI Investments is aware of this. “We've always voted against these, or abstain sometimes, because of the intentional effort to copy the exact language (we would otherwise support such an ask). Knowing the way advisory proposals work, the best practice after one got a decent number of votes is for the company to reach out to the filer and ask to engage. In these cases, one might be reaching out to a filer whose intentions are the exact opposite of what one might be trying to do,” Bonham says.

Who Gets There First?

The logical next question would be, if both anti-ESG and pro-ESG groups want to file a similar resolution (albeit with opposite intents), who gets on the ballot? That depends on who gets there first. The SEC allows companies to leave off duplicate proposals, so similar proposals appear on a ‘first-come-first-served’ basis. This is detailed in the SEC guidance around duplication, which states that a company can leave off a resolution, “If the proposal substantially duplicates another proposal previously submitted to the company by another proponent that will be included in the company's proxy materials for the same meeting.”

A case where this played out was with Pfizer. According to the Proxy Preview 2022 report, NCPPR copied verbatim the “RESOLVED” clause of the election spending values proposal submitted last year by Tara Health at Pfizer and sent it in early—while advocating against the causes Tara supports, chief among them reproductive health rights.

To Welsh, it is clear that this is a tactic used by anti-ESG groups. “The anti-ESG proposals explicitly use the same “RESOLVED” clauses, with an aim to block other filings within the current year, and potentially block these issues from the ballot in future years,” she explains.

How would ballots be blocked in future years? That is where the 2020 SEC rules come into play.

Why the 2020 SEC Rule Could Be a Game Changer for Anti-ESG Groups

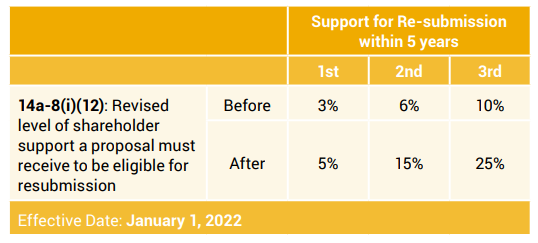

In a flurry of rushed proxy rulemaking in the latter half of 2020, the SEC sought to make it harder for investors to exercise their ownership rights in corporate elections. The shareholder resolution rule change required that refiled shareholder proposals should have previously attained much higher levels of support.

Prior to the rule change, thresholds had been 3% if filed once in the past five years, 6% if filed twice, and 10% if filed three times in the recent past. Starting 1 January 2022, new thresholds were set at 5%, 15%, and 25%, respectively. The measure had long been sought by pro-corporate lobby groups and was roundly decried by investors.

At the time, Morningstar had submitted a letter expressing concerns over this, saying in part “These low levels of support may disqualify diversity.”

In 2021, a lawsuit was filed disputing these changes. The plaintiffs argue that there are hundreds of examples of companies changing their policies and practices as a result of productive engagement with shareowners, yet a handful of corporate trade associations have engaged in an intense, multiyear lobbying campaign to curtail investors’ access to the proxy.

For now, the new thresholds stay, and so, if anti-ESG group proposals receive less than 5% of the vote, these issues are then off the table for the next three years.

Take, for example, the case at Costco Wholesale. The NCPPR filed a shareholder proposal asking that the company list on the company website the recipients of corporate charitable contributions of $5,000 or more. Costco investors gave the idea 3.2% support in January this year (though a greenhouse gas-focused resolution received 70% support.). As it received less than 5% of the vote, it is unlikely that a charitable giving proposal may reach investors for a vote for at least the next three years. However, Welsh feels this may have been expected.

“The charitable giving-related proposals are usually filed to identify donations to various causes, including Planned Parenthood. Traditionally, these do not have as much support. The racial justice and anti-critical race theory ones are relatively new, and we will need to wait and watch how these unfold,” she says.

There is one instance we examined, though, where a pro-ESG group countered an anti-ESG group, and the SEC left the decision up to the investors.

Section 3: The Curious Case of Johnson & Johnson

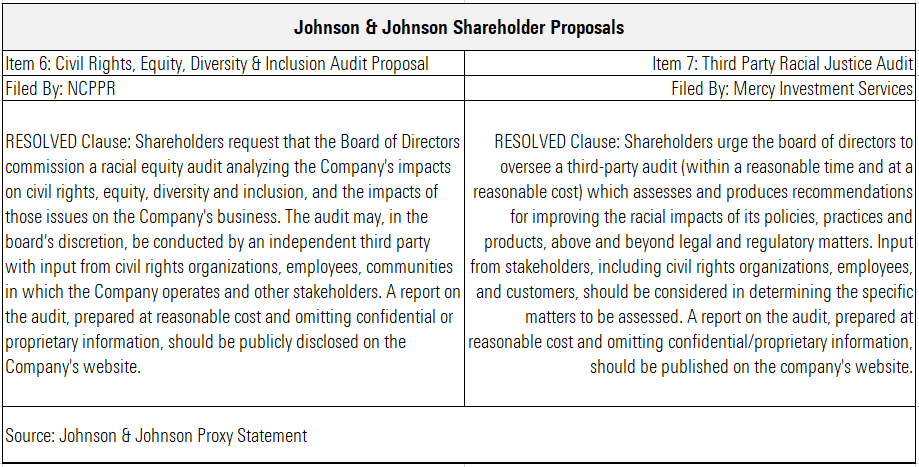

Johnson and Johnson (JNJ) will have its 2022 annual general meeting on 28 April. Ten shareholder proposals are on the ballot, labeled items 5 through 14. Here’s a look at items 6 and 7.

Although on the surface of it, the two appear very similar, the differences arise in the supporting statements.

The NCPPR statement says, in part that, “Some have pressured companies to adopt ‘anti-racism’ programs that seek to establish ‘racial equity,’ which appears to mean the distribution of pay and authority on the basis of race, sex, orientation and ethnic categories rather than by merit. Where adopted, however, such programs raise significant objection, including concern that the ‘anti-racist’ programs are themselves deeply racist and otherwise discriminatory.”

The Mercy Investment Services statement says, “Addressing systemic racism and its damaging economic costs demands more than a reliance on internal action and assessment. Audits engage companies in a process that internal actions alone may not replicate; unlocking hidden value and uncovering blind spots that companies may have to their own policies and practices. Company leaders are not diversity, equity, and inclusion experts and lack objectivity. Crucially, a racial justice audit examines the differentiated external impact a company has on minority communities.”

Meanwhile, Johnson & Johnson’s response to both is virtually identical.

So, why are both these issues on the ballot? Some answers may be found in the J&J No Action Letter written by the SEC in response to a challenge by the company of the Mercy proposal. The SEC says that “In our view, the Proposal does not substantially duplicate the proposal submitted by the National Center for Public Policy Research.”

It appears from the letter that Johnson & Johnson did not challenge NCPPR’s proposal but did challenge the Mercy one on the grounds of duplication. Essentially, the SEC concludes that it does not believe the two proposals are the same.

Now, it is up to the shareholders to decide what to do with each proposal.

Section 4: What Should Shareholders Do?

“A question for investors to consider when deciding how to vote is, “What is the intent here?” One way to answer that would be to read the entire proxy statement, including the summary, and not just rely on the “RESOLVED” clause,” Welsh says.

Another thing that could help is the track record of the filing organization. It is a tool that investors use when trying to understand the motivations behind the proposal. Even if the organization is new, look for whom it has worked with in the past – this can help provide insights into its intent and ideology.

For Bonham and NEI investments, this responsibility means digging deeper. “The way we've approached it, and the way most investors who are paying attention have approached it, is to say, this may make sense on the surface, but then, when you read the actual rationale behind it, we realize we are completely not aligned,” he says.

Bonham also sees this as an annoyance. “I can imagine it's a distraction. It’s just meant to be annoying, but I don't think there's any reasonable grounds for the anti-ESG groups to argue. I think it's a good sign that, even though there is this anti-ESG backlash, if you will, it is so muted and has almost no support from anyone, neither investors nor companies. I don't know that I would be able to say that even 10 years ago,” he adds.

Cook agrees, “Just a few years ago, it was relatively rare for shareholders to vote against company management on corporate ballot issues, especially among the largest mutual fund companies who cast votes on behalf of investors in their funds. Now, as companies find themselves losing a record number of votes, environmental, social, and governance advocates have a stronger hand when it comes to direct engagement with company managements over policies they are seeking to change,” she says.