On March 30, Morningstar published its Global Investor Experience report around fees and expenses. In this report, Canada received an overall grade of Below Average when compared with 26 other jurisdictions. This report serves as a supporting document, outlining further details around the Canadian investment funds market as they relate to fees and expenses.

The Cost of Advice and Distribution in Canada

In Canada, fees for advice and distribution are predominantly bundled in with the overall commission charged on the majority of mutual fund assets, despite our data showing that assets are shifting away from this arrangement. This differs from major markets like the U.S. where advice fees are commonly charged separately. Moreover, the fund distribution complex in Canada is very much vertically integrated, as the largest Canada-domiciled fund manufacturers have also built out vast retail distribution channels. This begs the question whether the total cost of owning a fund in Canada differs significantly from other markets when accounting for the bundled fee environment.

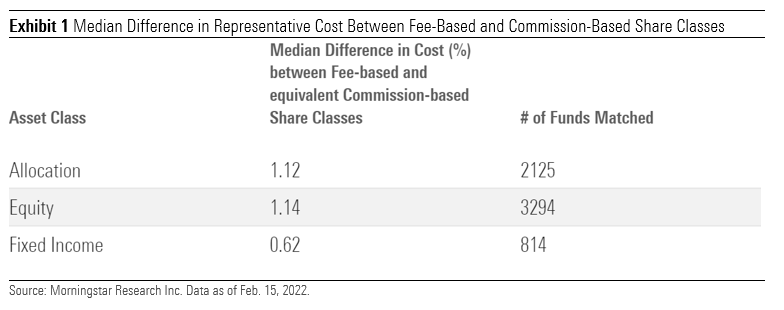

To understand the cost of advice and distribution, Morningstar hypothesized that each fee-based share class (where the cost of advice is excluded) could be matched to its closest commission-based equivalent (where the cost of advice is bundled) to determine the difference in fees, as stipulated by Morningstar’s representative cost methodology. In concept, the gap between the two closely related share classes would represent how much a Canadian investor pays for advice and distribution, assuming that an investor is indifferent between paying a bundled or separate fee to an advisor. Because share class naming conventions are not standardized in Canada, we employed a number of parameters to make the appropriate matches, including but not limited to portfolio identifier, base currency, minimum investment amount, distribution type (fixed or not fixed), and the Levenshtein distance between two fund names. In total, 6,233 fee-based share classes were mapped to commission-based equivalents. The difference in representative cost between these share classes was then aggregated, and a median was taken to reach what could be interpreted as the cost of advice and distribution in Canada, displayed in Exhibit 1.

From here, we can see that the median difference between fee-based share classes and their commission-based equivalents for allocation and equity funds sits at roughly 113 basis points. That is, a logical investor should be indifferent between owning a commission-based share class and paying the bundled commission, or a fee-based share class and then separately paying the advisor an overall management fee of 113 basis points. Interestingly enough, the same difference is much lower for fixed-income funds, which begs the question whether primarily fixed-income investors are better off holding commission-based share classes given that the difference is much lower.

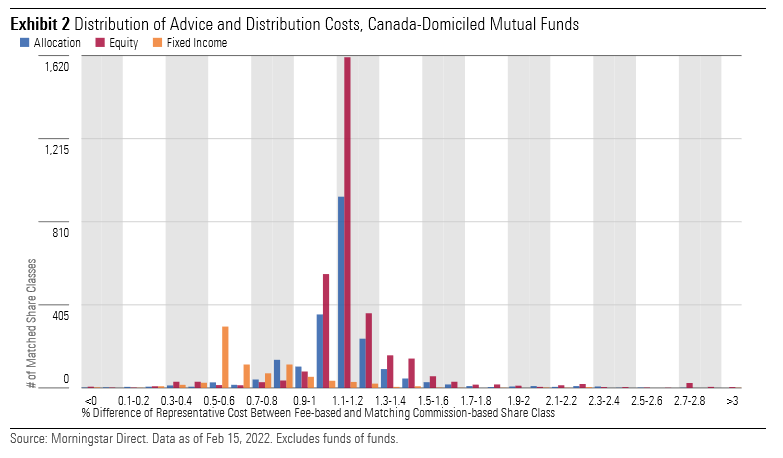

This said, the median difference may not tell the whole story, hence the distribution of differences is outlined in Exhibit 2.

For all three asset classes, the distribution of fee differences skews to the right, implying that there is a wider range of fee differentials that are greater than the median. For an investor, this means that probability-wise (if choosing a fund at random), it's more likely a better deal to own a fee-based share class if available.

Given this clear and quantifiable cost of advice, it is of vital importance that if an investor is only given an option to purchase a commission-based product, that they actually receive the paid-for advice. A survey conducted by the Ontario Securities Commission’s Investor Advisory Panel in 2019 illustrated that this isn’t always the case. According to those surveyed, 26% of investors with portfolios between CAD 50,000 to 100,000 (the most likely to purchase commission-based share classes) reported “no advice about planning for financial goals such as retirement, education or buying a home.” Since the time of the survey, the CSA has implemented the Client Focused Reforms, which stipulate requirements around suitability and client best interest. In concept, this would include an understanding of client investment goals, followed by a recommendation of an appropriate product. This is a significant step in the right direction, which otherwise would be a cause for concern given the vertically integrated nature of the Canadian financial-services industry, and its eerily similar structure to Australia’s pre-Hayne Royal Commission landscape. However, it is still arguable whether this initial assessment of risk and subsequent recommendation of a product would constitute as "ongoing" advice which, in effect, is what an investor pays for year after year while owning a fund.

Canada-Domiciled Sustainable Funds

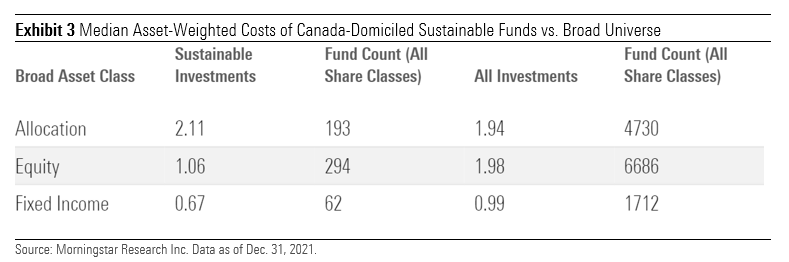

Given the continued interest in sustainable investing and noting that assets in sustainable mutual funds and ETFs doubled over the course of 2021, we would be remiss if we did not mention the costs of investing sustainably in Canada. Using a similar methodology as the Global Investor Experience, the below exhibit shows median asset-weighted representative costs for Canada-domiciled sustainable funds compared with the broader universe.

Here, we note that funds that state they use a sustainable approach to investing (inclusive of ESG integration, impact, and environmental sector funds) are in fact less expensive on the above basis for pure asset classes and somewhat comparable for allocation (balanced) funds. This comes with the noted caveat that we are working with a relatively small sample size of sustainable funds. Regardless, we are hopeful that this trend continues as sustainable investment choices continue to expand.

%20(1).jpg)