Hetty Green was known as the “Witch of Wall Street.” She earned this moniker partly due to the single, dour, black dress that she wore daily, but mostly for her reputation as a litigious and greedy woman whose miserly ways led to her son losing a leg.

During the Gilded Age of Wall Street, while the Carnegies and Rockefellers were building their fortunes and their mansions, Hetty inherited her own small fortune of $5 million. Through wise investments, she turned this into more than $100 million (more than $2 billion in today’s dollars), making her the richest woman in the world at the time. Unlike her better-known contemporaries who left legacies in business and philanthropy, Hetty left a legacy of tightfistedness and self-delusion.

As the story goes, when Hetty’s son injured his leg, she could have taken him to the best hospitals in the world but chose instead to dress in rags and take him to the free clinics in New York City. In Hetty’s defense, she did take him to the best physicians, but she didn’t want to pay them, instead learning what hours they volunteered at the free clinics and visiting then. The time it took to search for this free treatment led to an incurable case, and rather than heal the leg, the doctors removed it. When she suffered a hernia herself, she refused to have an operation and used a stick to put internal things back in place when necessary.

Sound Investments, Unsound Mind

Hetty built her fortune by buying undervalued assets and holding them until they were in high demand. She sold only when buyers came hounding, and often still turned them away. She also lived an extremely frugal lifestyle. While others built family compounds, Hetty lived in a small apartment. She bought a new dress only when her current one wore out.

Some may see Hetty as a model of clever money management, and she was quite a brilliant investor. By any financial measure, Hetty would be said to have been in excellent financial health, but I disagree. She lived simply, but not contentedly. She spent many years of her life in legal battles with family over assets she believed should have been given to her rather than charity. Although Hetty had objectively more money than almost everyone else in the world, she still believed she did not have enough. She believed it so strongly that she spent her life, and ruined her relationships, in pursuit of more.

What Is Financial Well-Being?

I tell Hetty’s story because she helps illustrate an important fact: Financial well-being is not only about numbers. It’s also about the stories we tell ourselves because of those numbers.

The financially healthy enjoy the emotional security that comes from knowing that they have enough to weather life’s storms, to rebound, and, if necessary, to rebuild. On top of basic security and resilience, the financially healthy experience a sense of satisfaction and contentment in their financial lives.

Does Wealth Equal Well-Being?

The purpose of wealth is to support well-being, but well-being is not a necessary or guaranteed byproduct of wealth. Yes, financial stability can help reduce all kinds of life stressors, and research does reveal a positive relationship between income and life satisfaction, but it’s not necessarily true that more wealth will bring with it a higher quality of life. The idea that wealth = well-being is a mental shortcut that doesn’t hold up under scrutiny.

To illustrate this point, we conducted a small survey in 2021 where we asked a representative sample of around 500 U.S. residents about their emotional experiences with money. People reported how often they had experienced certain emotions with respect to their finances over a period of three months. There were five positive emotions (joy, peace, satisfaction, pride, and contentment) and five negative emotions (anger, sadness, helplessness, fear, and stress). For each emotion, they answered on a scale from “Never” to “Constantly” with Never = 1, and Constantly = 5.

The responses allowed us to create a Financial Emotions Score that ranged from negative 20 to positive 20. A score of negative 20 would indicate that someone constantly felt all five of the negative emotions and never felt any of the positive ones. A score of 0 indicated equal frequency of positive and negative emotions, and a score of 20 indicated constant positive feelings and no negative emotions with respect to their finances. Using this score, we then looked for financial and mental factors that contributed to net positive emotional experiences with money.

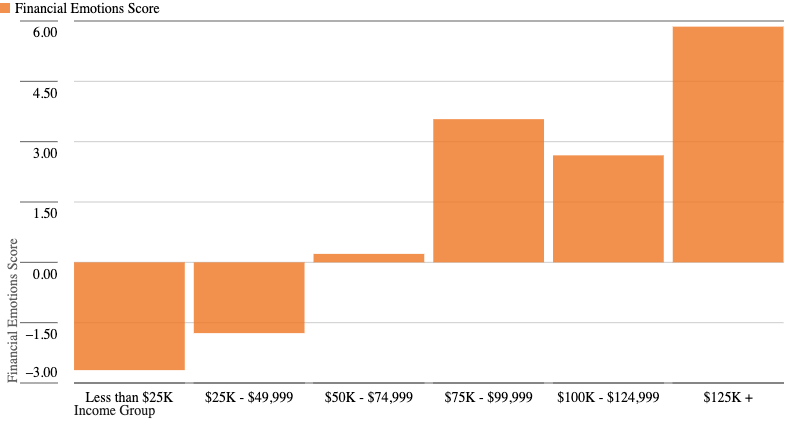

We found that those with higher incomes did have significantly more positive emotional experiences, as shown below.

Financial Emotions by Income Group

There was a clear, positive relationship between income and financial emotions, but this doesn’t tell the whole story.

We also asked survey participants about their beliefs and attitudes with respect to money. Specifically, one question asked how much they agreed or disagreed with the statement, “I can handle whatever comes my way, financially,” where 1 = “completely disagree” and 10 = “completely agree.” This was used to measure their financial confidence, or the belief that they could bounce back from difficulty.

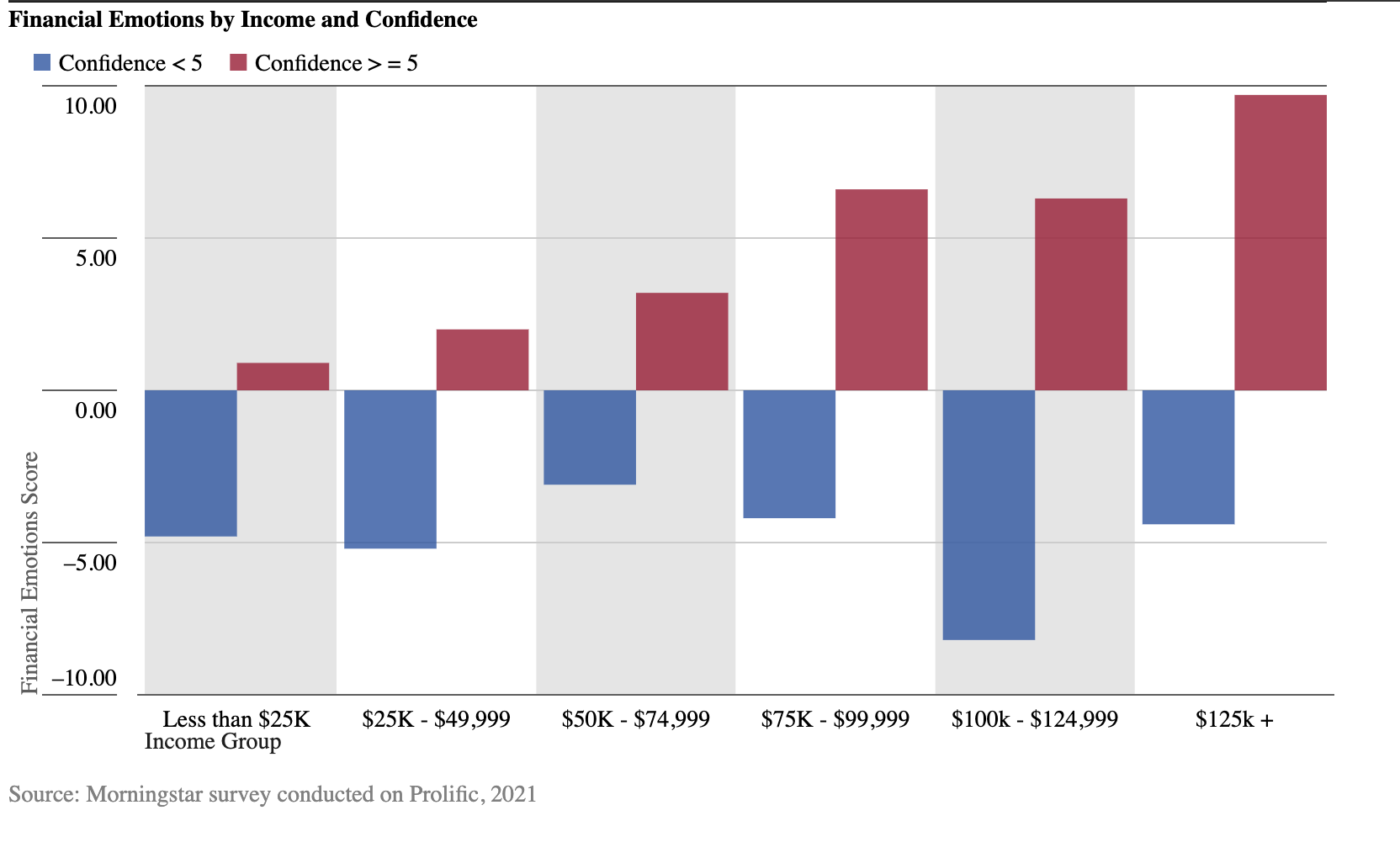

Using this measure of confidence, we then grouped people based on whether they mostly agreed or disagreed with this statement and then looked at the relationship between income and financial emotions again. The results tell a very different story, as shown below.

Financial Emotions by Income Group. Those who had high confidence reported net positive financial emotions regardless of income group. Those with low confidence reported net negative financial emotions in every income group.

In every income group, people who believed they could handle financial difficulty also reported experiencing mostly positive emotions with respect to their money, and in every income group, those who did not believe they could handle difficulty experienced mostly negative emotions. In other words, confidence appears to be more important to financial well-being than income. For the stats nerds among my readers, the standardized beta coefficients when regressing financial emotions on income and confidence were 0.108 and 0.576, respectively, making the effect size of confidence more than five times that of income.

In short, when it comes to the emotional side of financial health, income matters, but the beliefs we hold about money and our own ability to manage it matter more. A person can have a high income, but if their financial mindset is weak, they may still have a very low quality of life with respect to their money.

Building Financial Confidence

Everyone has stories in their mind about their own financial circumstances, abilities, and status. Some stories are true, and some are not. Some are healthy, and some are not. By examining and editing our financial beliefs, we can improve our financial health and quality of life, even if the numbers in our bank accounts stay the same.

My goal as a financial psychologist is to help people achieve financial well-being wherever they are on their financial journey, even well before they reach their long-term financial goals. To this end, I believe it’s important for people to build a sense of financial confidence that is not attached to one’s income or net worth but to their ability to manage resources well, to make high-quality decisions, and to handle inevitable setbacks with creativity and grace. These skills can be developed regardless of your current income or net worth.

If your own financial confidence is low, here are a few tips to help build a belief that you can, in fact, handle whatever comes your way. Some of these pertain to those just starting out and others to those who have already accumulated some assets. Take what fits, and leave the rest:

1. You’ve done it before. You can do it again. Think about a time when you experienced a setback in the past. How did you overcome? What safety net or resources did you rely on to help you rebuild?

2. Take stock of your safety net. This includes emergency cash, liquid assets (anything you could get your hands on in a week without penalties), unemployment insurance, debt deferral programs, and even friends and family members who might lend a hand, a home, or moral support if you fall on hard times.

3. Evaluate your insurance policies. Would increasing your coverage help you feel better prepared against catastrophe?

4. Diversify your assets: stocks, bonds, real estate, Treasuries, cash, and so on. By holding many different types of assets, you lower the chance of losing it all in a downturn. The stock market may crash, but your other assets may be doing just fine, or vice versa.

5. Evaluate your human capital. If you were to lose your job, the value of your time, skills, and experience would not be diminished in the least. You will have only lost a buyer. In fact, the value of your work will likely have increased since you were hired, so the loss of one position could be a springboard to a much better situation.

6. Most important, remember you are more than your money. People who attach their self-worth to their net worth are at higher risk for depression and life dissatisfaction.

Hetty Green’s example reminds us that wealth alone is insufficient for well-being. A mindset of scarcity, bitterness, or fear is antithetical to contentment. On the flip side, if your financial attitudes and beliefs are healthy and empowering, you can experience peace and well-being even in times of setback or loss.