Global fund portfolio managers should be country agnostic and go where the best stock picks lead. But a new piece of research finds that a significant proportion of managers have a bias toward the country in which the fund resides.

Home country bias is a topic we have previously discussed, and occurs when an individual, or fund invests disproportionally in securities that are locally domiciled. It is not a phenomenon that's specific to Canadians, but is present in most developed markets around the world.

One would be forgiven for assuming that a “global” fund would invest more aggressively outside of one’s native shores. But this is not always the case, as Derek Horstmeyer, professor of finance at George Mason University’s Business School, found when he examined the holdings of global equity funds issued in their home currency in 16 different countries.

His research shows that home bias varies widely by country. Spanish managers on average have a eurozone weighting of 20.88% while the MSCI ACWI index has a weighting of 13.1% for that region. The net result is that Spanish managers have an overweight of 7.78%, the highest among the 16 countries surveyed. The next two countries with the heaviest over-weights are Germany, at 5.19 percentage points, and the U.K., at 3.83. Canada comes in with only a slight overweight of 0.8 percentage points.

“Fund managers, like those in the U.K., tend to overweight their home country or region when constructing global equity funds for investors in their country. Others, like those in the U.S., tend to underweight their home country or region,” Horstmeyer noted.

Some countries are underweight, such as South Korea coming in at -1.01 percentage points, Belgium at -2.29 and France at -2.99. U.S. managers have the biggest underweight: -5.57 percentage points.

Do Canadian Global Fund Managers have Home Country Bias?

Skeptical at the outset of Horstmeyer’s findings, Morningstar Canada’s Head of Manager Research Danielle LeClair dug into the data on 608 Canadian Global funds and came up with unexpected results. First of all, she notes, “global funds constitute the largest equity category in Canada”.

While the MSCI ACWI index gives a 3.1% weight to Canada, LeClair found that 328 funds, a little more than half the sample, have more than 3% in Canada. But what was really surprising to her was that “about 151 have a weighting above 10%.” Many of those Canadian overweighters have a high Canada calorie count: two funds weigh in at 72.2% and 60.4% presence in Canada, nine above 40%, and 57 above 30%.

This is a problem. As Morningstar’s Director of Investment Research Ian Tam explains, home country bias comes along with some significant costs. “For one, under-diversifying means that you're missing out on opportunities for growth outside of your home country. It also represents a double whammy when it comes to risk, which diversifying your portfolio across different countries helps eliminate,” Tam explains.

Investors might be hoping to diversify out of that with a global fund – but if the find has over 70% of its holdings in Canadian securities, the entire point is missed.

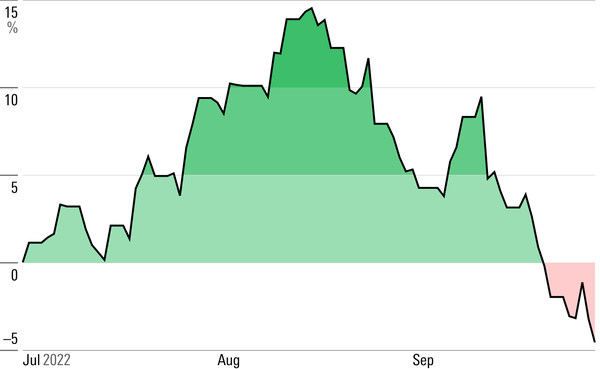

If Funds Have Been Underweight U.S., They’ve Underperformed

Whether a fund is overweight or underweight its home country also correlates with returns, Horstmeyer finds.

The highest overweighters such as Spain, Germany and the U.K. come in with some of the lowest 10-year average U.S. dollar returns: 9.16%, 9.93% and 11.38% respectively. The only outlier is Italy which, in spite of a slight local underweight of -1.83 points, comes in with a 10-year return of 10.93%.

The most important variable is U.S. allocation. “If you were underweight U.S., you did poorly from 2011 to 2021, as the S&P 500 did better than any European index,” Horstmeyer says. Indeed, with a percentage point overweight of 10.54, Belgian funds deliver one of the strongest 10-year returns: 12.24%. France, with a 9.83 overweight comes ahead of everyone else at 13.63%. Canadian funds deliver somewhat in the median range: 11.93%. U.S. global funds confirm the reading: with a U.S. underweight of -5.57 percentage points, they barely do better than their U.K. counterparts, which weigh in at -7.02.

Can the Data Be Accepted at Face Value?

LeClair questions certain assumptions of Horstmeyer’s research. First, how does he determine the domicile country of managers? For example, many Canadian global funds are managed by sub-advisors located in the U.S. or elsewhere. Can he account for those? Horstmeyer readily recognizes a certain weakness there: “I can’t control where the portfolio manager resides, only where the fund is offered,” he says.

LeClair raises the possibility that part of managers’ home bias could be “a reflection of home market demand, or investor home bias.” It would also vary by region; for example, an investor who invests globally in Canada could have very different expectations from those of a U.S. global investor.

Since the home choice is so large in the U.S., a U.S. investor would expect a global fund manager to invest outside U.S. frontiers. But in Canada, where home choices are much more limited, an investor could expect that a fund manager, even a “global” one, would still stick close to home to some extent.

Another objection could point to the fact that most global fund managers are bottom-up stock pickers. Whether their selections land in one country or another is only something you can account for after the fact. Country over- or underweight is a consequence, not a driver.

Horstmeyer counters: “We tend to consume more favourably based on the info that is in front of us. If John Deere is in Wisconsin in front of you, you have larger chances of investing in it.”

“For investors, paying attention to which fund managers are overconfident in the home country’s future prospects could help boost your returns. And in any case, a more neutral weighting would provide greater diversification,” Horstmeyer concludes.