There’s nothing like a bear market to bring out the doom and gloom.

Much of the debate this year has been focused on whether the economy is headed for recession and if so will it be mild or severe. Now, though, there’s a darker discussion taking place: The potential for a financial crisis.

The chorus of nervous voices has been broadening, especially in the wake of turmoil in the United Kingdom’s government bond market that has forced emergency actions from the Bank of England.

Worries that the unprecedented pace of federal-funds rate increases by the Federal Reserve could have unintended consequences in global financial markets are now front and center. The concerns include a “liquidity event” in the credit markets in which a major player in the financial markets is unable to refinance debt, or a macroeconomic level crisis triggered by the surge in the value of the dollar that pummels other currencies and leads to defaults on dollar-denominated debt, which occurred in 1990s in the emerging markets.

Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers is the latest to add his voice to these concerns, warning in a recent interview that he sees “tremors” in the markets. “We are living through a period of elevated risk, and earthquakes don’t come all of a sudden. There are tremors first,” he says. He cautioned that he wasn’t predicting a financial crisis, but “in the same way people became anxious in August of 2007, I think this is a moment when there should be increased anxiety.”

Now the question for investors is whether the Fed will be able to pursue its goal of achieving price stability by raising rates or will it be forced to abandon the inflation fight to ensure financial stability.

“Financial crisis is a new focus,” says John Canavan, lead analyst at Oxford Economics. “It does appear that growing financial stability risks raises the possibility that the Fed may need to react to financial stability concerns before its goals are reached on inflation.”

None of this is cause for investors to panic. The Fed has tools in its arsenal and at its disposal that can be implemented quickly to stabilize markets if need be. Since the Great Financial Crisis it has added two new facilities: The Standing Repo Facility (SRF) and the Foreign and International Monetary Authorities (FIMA) Repo Facility, which would allow market makers to temporarily exchange U.S. Treasury securities for U.S. dollars, though both remain untested. The new facilities were created to address a wide demand and supply imbalance that occurred in September 2019 that led to an outsize spike in rates and deteriorating liquidity conditions in March 2020 as a result of the pandemic.

What Are the Warning Signs?

Signs of growing stresses in the global financial markets have been percolating quietly all year, but erupted into sharp relief in the past few weeks as the BOE has been forced repeatedly to intervene in the market for U.K. government bonds—known as gilts—to keep it functioning.

While no one is predicting the U.S. will find itself in similar circumstances, market strategists say diminished liquidity in the U.S. government bond market bears monitoring, especially at a time when debt loads are at extreme highs and the Fed might be limited in its ability to respond given the level of inflation. Illiquid conditions occur when there are no buyers for assets and demand disappears. That forces prices lower and creates more volatility and dislocations in markets.

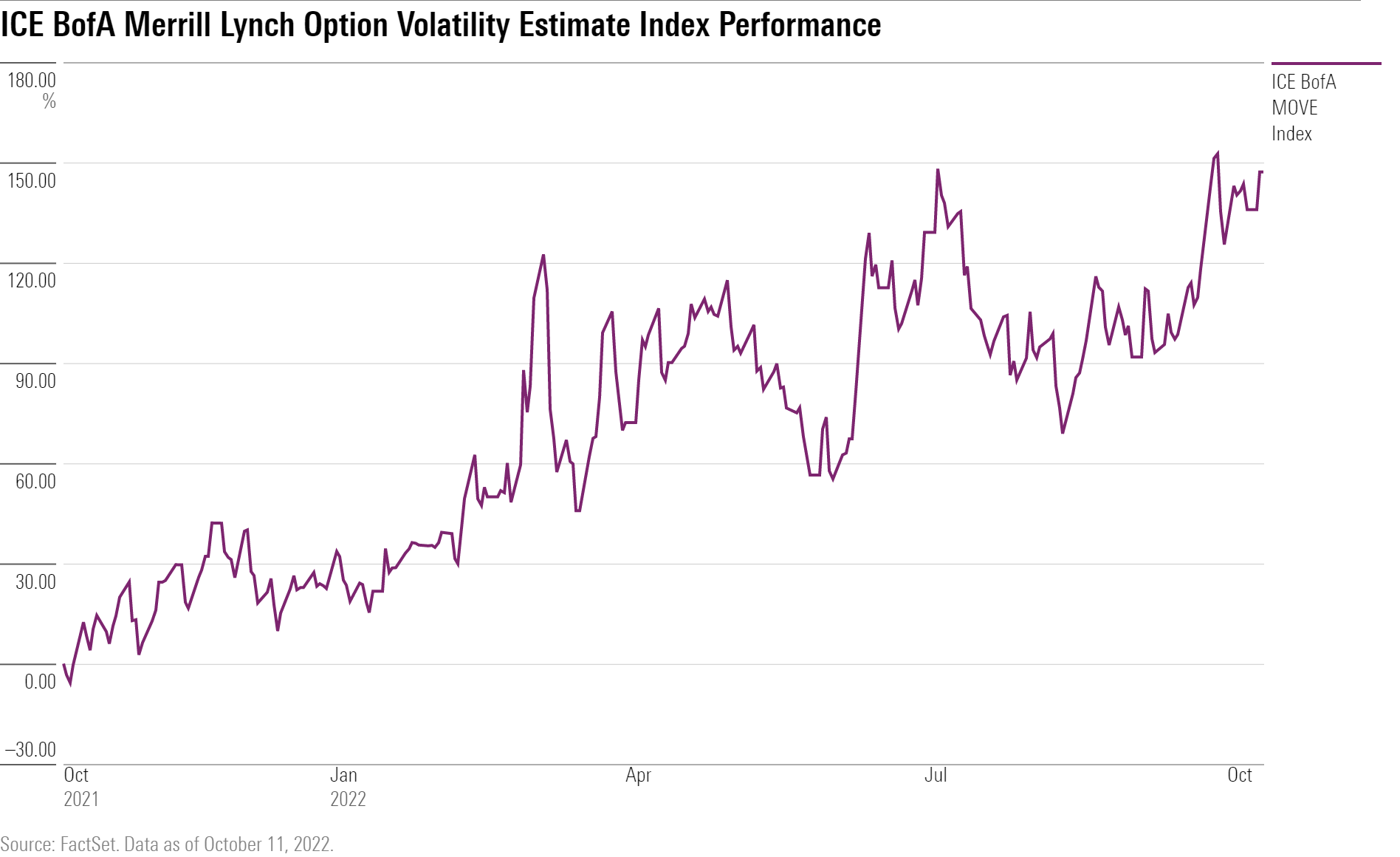

“Treasury market volatility has been increasing as liquidity conditions remain impaired amid a highly uncertain macroeconomic and rate outlook,” Canavan wrote in a recent report. “The driving forces behind these trends show no signs of abating.”

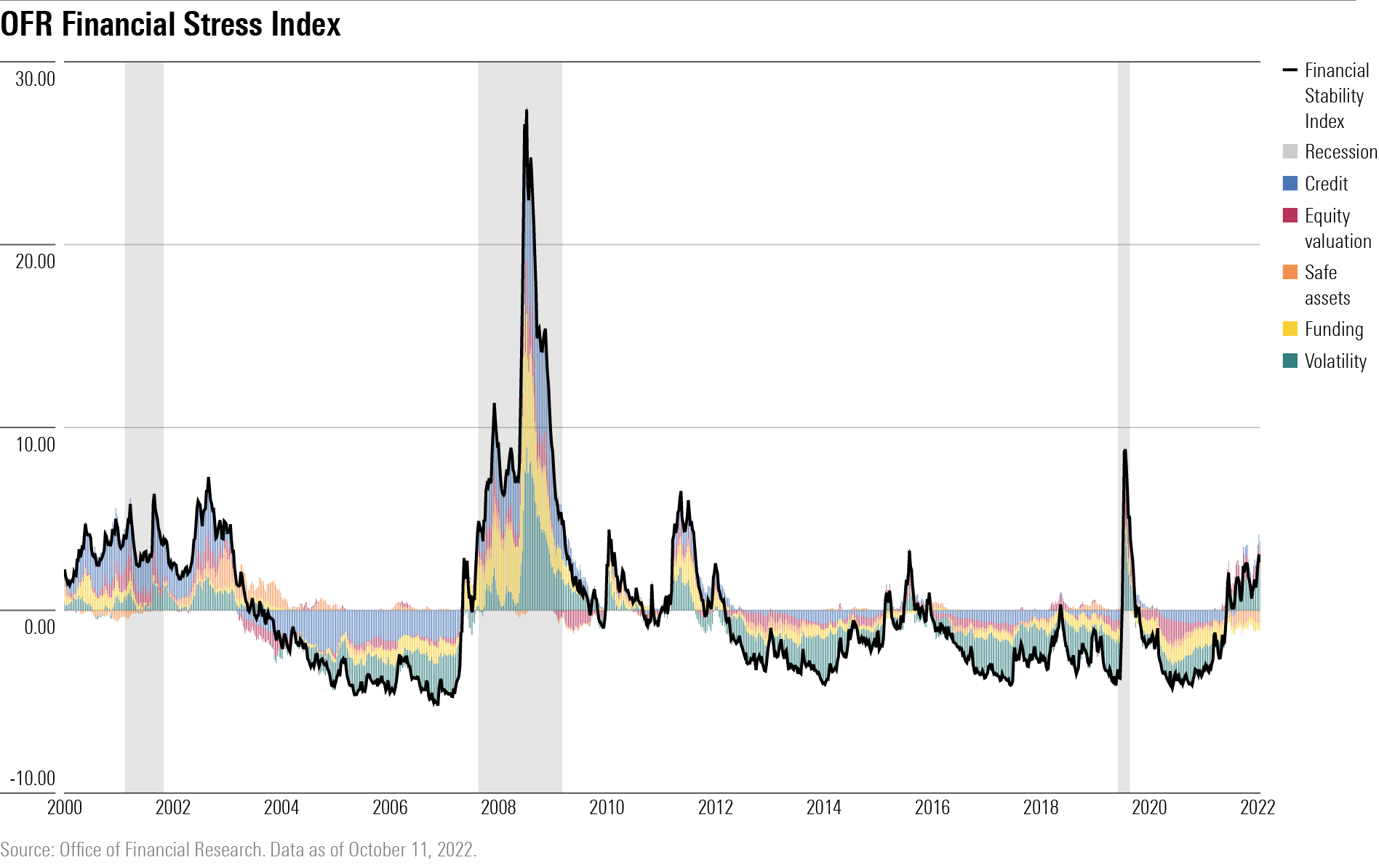

Indeed, the Treasury’s Office of Financial Research’s Financial Stress Index is at its highest levels since 2010, not including the spike in 2020 related to the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns. The index measures stress in the global financial markets based on 33 different variables such as yield spreads, equity valuations, funding activities, and interest rates.

“I think it’s overhyped but it’s a warning,” Ralph Axel, interest-rate strategist at Bank of America, says of low liquidity in U.S. Treasury markets. “No one has any confidence where interest rates are going. There’s the potential they go to 8%. No one wants to buy and warehouse bonds under these conditions.”

He notes that in addition to the Fed’s job of maintaining economic conditions that allow for stable prices and maximum employment levels, it has a third mandate as lender of last resort, ensuring markets function smoothly and credit continues to flow.

“The Fed has a lot of weight and responsibility on its shoulders,” says Axel. “It’s unfortunate they have the largest inflation problem since the 70s. The two don’t go well together. They don’t have the ability to trade off one for the other because inflation can be so debilitating.”

What Triggered These New Fears?

The U.K.’s gilt market seized up in late September as the yield on the 30-year gilt rose by 1.60% over four straight days to a high of 5.14% before falling to 4% in one day. Bond yields move inversely to prices and these huge swings don’t typically occur in the government debt markets of developed countries.

The pound, already weakened by a U.S. dollar on steroids, plunged further after Britain’s new conservative government proposed a budget promoting unfunded tax cuts that would have added to deficits and provided stimulus at a time when the central bank has been trying to rein in inflation that is already at 9%. The dislocations forced the BOE to intervene on Sept. 28 and buy bonds to keep the markets functioning, and to stabilize pension funds that were at risk of collapse.

As recently as Tuesday, the BOE expanded its purchases of gilts for the second time in two days ahead of the scheduled end to their buying program Friday. In a statement, the BOE said, “Dysfunction in this market, and the prospect of self-reinforcing ‘fire sale’ dynamics pose a material risk to U.K. financial stability.”

U.K. pension funds that had invested heavily in derivatives known as liability-driven investments, or LDIs, linked to British government gilts during an extraordinarily lengthy low-rate environment, needed rescuing. Leveraging the LDIs freed up cash for the pension funds to invest in riskier but higher-yielding assets such as stocks, real estate, and private equity.

The strategy backfired when the BOE, faced with rising inflation and a depreciating pound, began boosting interest rates. That created losses on the LDI investments that were then compounded by margin calls, which occur when accounts fall below a certain value and prompts lenders to demand repayment. That results in forced asset sales and starts a vicious cycle.

“Liquidity events typically arise from surprises,” says Dan Kemp, global chief investment officer at Morningstar Investment Management. “The U.K. mini-budget was a big surprise. When everyone rushes to the doors at once, this creates a flow problem.”

Shocks in the financial system often stem from shifts in interest rates that catch investors off guard, and expose vulnerabilities and an interconnectedness among financial entities that aren’t necessarily obvious. Not since the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-2009 has there been such intense focus on the possibility of a systemic financial shock.

While the banks are well-capitalized and under greater regulatory oversight since that time, risks have shifted to non-bank institutions such as hedge funds, pension funds, and asset managers that don’t have the same regulatory constraints as banks.

“Banks are well capitalized and there is sufficient support for U.K. markets,” says Morningstar’s Kemp. “But it doesn’t change the fact we live in quite shocking times and the probability of a liquidity event is higher.”

What Will the Fed Do?

Fed chairman Jerome Powell has said repeatedly that the central bank will maintain its aggressive stance until there are strong signs that inflation is under control. Fed governors in recent weeks have echoed the hawkish sentiment. Futures activity as gauged by the CME FedWatch Tool gives an 80% chance of another 0.75 percentage point increase in the federal-funds rate in November when the Federal Open Market Committee next meets.

With rates returning to more normalized levels from near zero to at times negative levels of the past 15 years, markets have had a hard time adjusting to the new normal, says Canavan. That’s added to volatility.

“The markets have consistently underestimated the Fed’s hawkishness and it’s determination in stamping out inflation,” he says.

Canavan is forecasting a 0.75 percentage point rate hike when the Fed next meets in November and a 0.50 percentage point increase in December. He doesn’t expect further rate hikes in the new year, but sees the Fed maintaining the pace of quantitative tightening. And he predicts a modest recession in the first half of 2023 and improvement in the second half.

When Will Investors Get the All-Clear Signal?

“What we’re living through is an economic pulse driven by the pandemic,” says Kemp of Morningstar. ``Some things that appear to be permanent will be fleeting. Investors have to plan for a range of possible outcomes and position for the future. We would encourage investors to become more granular in the way they think about the markets.”

Investors should build portfolios “up from the bottom,” rather than trying to shape them according to macroeconomic forces, he says. Focus on particular companies, sectors, industries, and regions that represent bargains, not just discounts to previous premiums. Invest with a long-term perspective and stay invested, says Kemp.

Markets likely will remain under pressure until liquidity in the Treasury markets improves, volatility declines, and the dollar pulls back.

“All that will be difficult to achieve until we see a clear end to the Fed’s tightening path,” says Canavan of Oxford Economics, noting a greenlight would occur if the Fed were to suggest an end date for its quantitative tightening program.

This article originally appeared on Morningstar.com