Holiday spirits turned into animal spirits in November as investors feeling festive celebrated by buying stocks and driving major indexes higher.

But investors in U.S. stocks may be partying too early, says Lisa Shalett, chief investment officer at Morgan Stanley Wealth Management.

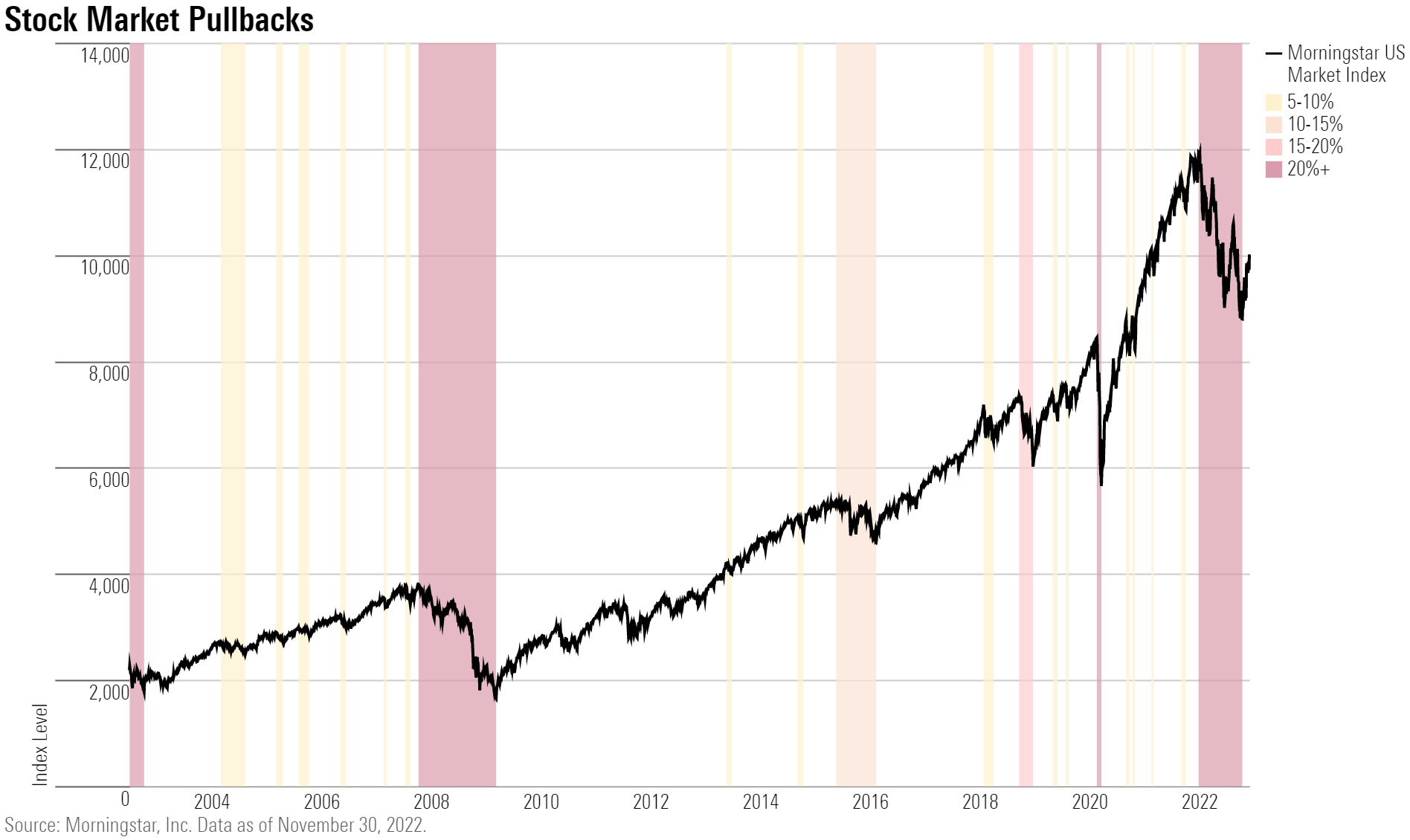

The Morningstar US Market Index gained more than 5% in November, with help from a 7.5% rally during a two-week stretch from Nov. 9 to Nov. 23. Since the current bear market low on Oct. 12, the market has rallied 13.7%. For the year, the U.S. market is down 15.62%.

A major catalyst for the rally has been optimism that inflation has peaked and that the U.S. Federal Reserve will begin to slow the pace of rate hikes at its meeting next week.

Indeed, Fed Chair Jerome Powell has said at a speech last week that it “makes sense to moderate the pace of our rate increases,” and added that the central bank may begin slowing the pace as soon as this month.

The sense that better times are ahead has led to hopes that the most recent bear-market low set the bottom for stocks.

Just Another Bear-Market Rally

The recent exuberance in the stock market “is not the start of a new bull market,” says Shalett. Rather, “it is in our view yet another bear-market rally.”

While Shalett believes the Fed won’t have to raise interest rates as high as many in the markets currently expect, that alone won’t be enough to end the bear market, she says.

"Wall Street wants to celebrate a slowing of the pace of (Fed) tightening,” says Shalett. "It is so premature. The Fed is still tightening. Equity bear markets don’t end with the final Fed hike, they end when earnings expectations bottom.”

A growing number of Wall Street firms and mutual fund companies are telling investors to lower their longer-term expectations for returns on stocks to below what has historically been the case. Others are saying that in the short-term, bonds are likely to be a better source of returns than stocks.

Shalett is in that camp for 2023, expecting that by the end of the year, stock market levels will be in the same range as they are now, at best.

"It will be a very drawn out, painful roller-coaster to nowhere,” she says.

Stock Valuations Still Too High

Shalett’s reasoning boils down to the fundamentals: In her view, stock valuations remain richly priced and are at risk of another 10%-15% drop as sales and profits come under pressure, as she expects they will in the coming year amid a "materially” softening economy.

Stocks trade at a steep multiple of 20 times the US$195 a share forward earnings estimate Morgan Stanley expects companies in the S&P 500 index to deliver next year, and that’s without factoring in a possible recession, which the firm isn’t predicting.

Even at the much higher Wall Street consensus forecast of about US$231 a share, stocks still appear expensive at 17 times estimated earnings. Shalett notes that with inflation above 3% and long-term government bond rates above 3.5%, a more typical forward price/earnings ratio would be 15 to 16 times earnings.

The S&P 500′s forward price/earnings ratio topped out at 23.2 times in early September 2021, fell to 21.4 times in January, and reached 15 times at the June low.

The price/earnings ratio reflects what investors are willing to pay for future earnings. When multiples are expanding, it’s a sign of confidence that companies’ earnings and cash flows will be increasing and investors are willing to pay a higher price for those profits. Conversely, when multiples contract, investors are discounting deteriorating earnings and demanding lower prices for those earnings.

Earnings Estimate Cuts Will Drive Stocks Lower

Shalett says that the disconnect between stock prices and estimated earnings could spell trouble for stock valuations, and argues better total returns will be found in U.S. Treasuries, municipal bonds, and investment-grade corporate bonds.

"We’re very concerned with what happens to S&P 500 earnings next year,” she says.

Shalett notes that many stock analysts and corporate managements are unaccustomed to an inflationary environment and are underestimating the challenges presented by the current economic environment.

She’s concerned that profits have been artificially propped up for the past two years by stimulus actions and pandemic-related behaviors, and that corporate managements are conflating nominal sales with real sales. Also, not only have companies particularly in the services sector been able to pass through price increases to consumers, they’ve been hiking prices well beyond their cost increases, Shalett says. That is a practice that is increasingly less tenable.

"Their pricing power is going away, and they will lose volumes and pricing simultaneously,” she notes.

That dynamic isn’t yet reflected widely in analysts’ forecasts.

Consumers Are Becoming More Stressed

Signs that consumers are more stressed are becoming more pronounced, including the most recent survey from The Conference Board that showed consumer confidence in November fell for the second straight month, she says. The reading of 100.2 was the lowest since July. The Conference Board’s Present Situation Index, which measures how consumers view current business and labor market conditions, and its Expectations Index, based on the short-term outlook for income, business, and labor market conditions, also declined.

"Inflation expectations increased to their highest level since July, with both gas and food prices as the main culprits. Intentions to purchase homes, automobiles, and big-ticket appliances all cooled. The combination of inflation and interest rate hikes will continue to pose challenges to confidence and economic growth into early 2023,” the board said in its release.

Another sign consumers are stretched, says Shalett, is that revolving credit cards are being used for more purchases, and bank charge-off rates for defaulted credit card debt have been increasing since the fourth quarter of 2021, although from a low level.

Investors have been buoyed lately by glimmers of good news that suggest the Fed’s fight against inflation is progressing, the better-than-expected October reading on the Consumer Price Index report, for one. And Shalett agrees the evidence suggests inflation has peaked. In addition, prior to Powell’s remarks Wednesday, a majority of Federal Reserve officials had agreed at their last policy-setting meeting that slowing rate hikes from the recent series of 0.75-percentage-point increases would be appropriate.

Markets now expect that the Fed will raise the federal-funds rate by 0.50 percentage points at this month’s meeting from it’s current target of 3.75%-4.0%.

Powell, however, in his speech this week at the Brookings Institution think tank cautioned that monetary policy may stay restrictive for a longer period. ``It is likely that restoring price stability will require holding policy at a restrictive level for some time,” he noted.

For her part, Shalett says the Fed ultimately won’t have to raise rates as high as the markets are currently expecting. Morgan Stanley puts the Fed’s end point for raising the federal-funds rate at 4.625%, lower than the level of the consensus peak of around 5.0%, as measured by the CME FedWatch Tool.