Thanks to the generally bullish market that prevailed until this year, mutual funds and ETFs created a total of US$16.2 trillion in shareholder value over the 10-year period. These results would look worse if they included funds that disappeared through mergers or liquidations, but it’s safe to say the majority of funds have generated positive results in dollar terms over the past decade. Now, let's look at the opposite perspective, focusing on funds that have lost value for shareholders over the same period. We'll focus on ETFs in particular, as many thematic products in that asset class have fallen the furthest.

The Results

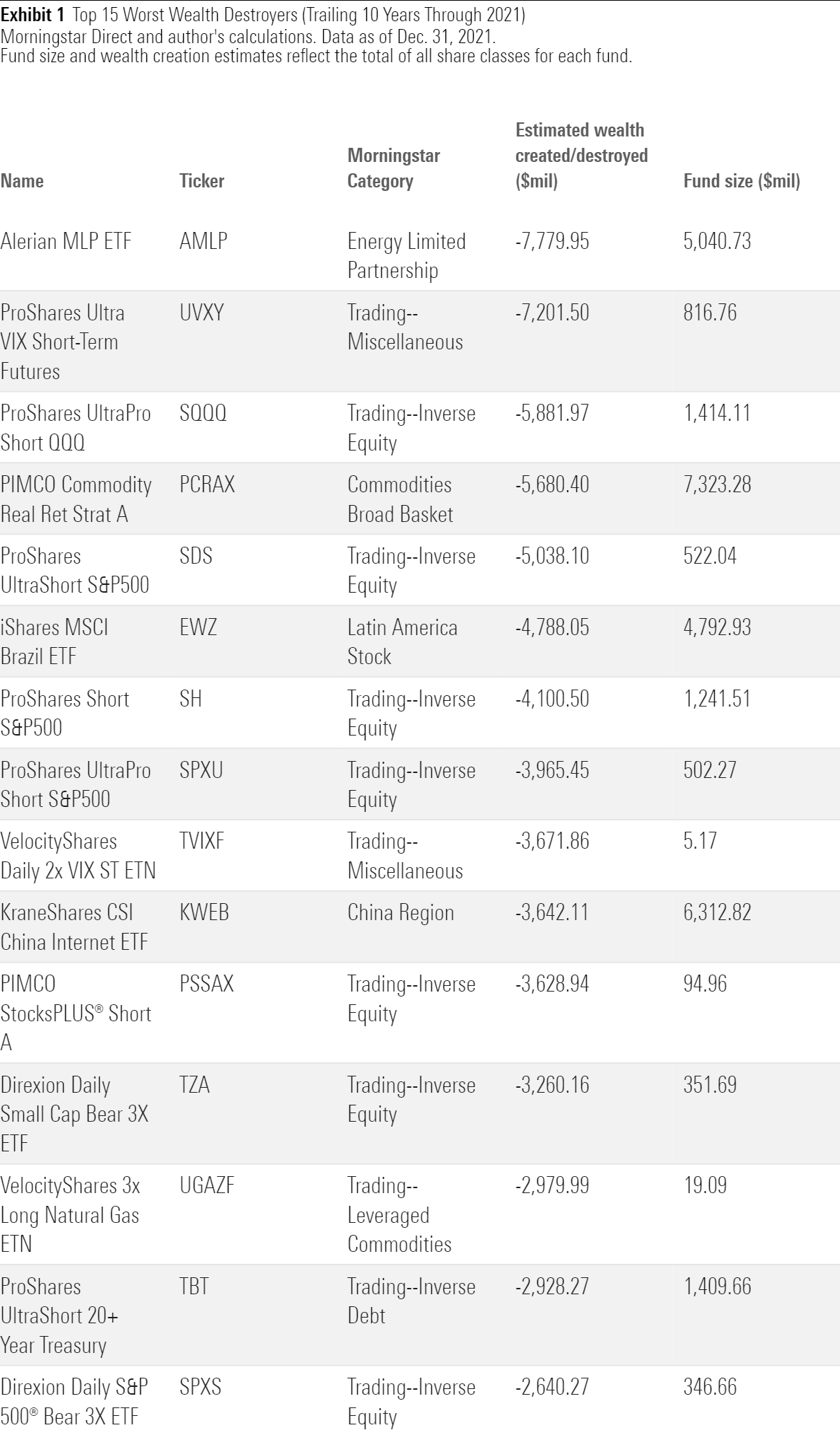

While the top wealth creators were all large, well-known names from some of the largest categories based on asset size, the wealth destroyers are a motley crew of more specialized fund categories.

By definition, the biggest funds will create or destroy more value in dollar terms. And money tends to flow to the funds that have been successful in the past, so the big generally get bigger. The converse is also true: Smaller funds with weaker returns are guaranteed to create less value, or even destroy it, in some cases.

ETFs have many things going for them—including low costs, tax efficiency, and typically a passive investment approach that makes them suitable building blocks for diversified portfolios—but they also have a dark side. Just as Bogle feared, ETFs often focus on narrowly defined market sectors and asset classes, making them potentially dangerous when used by investors with a speculative bent.

When I looked at the biggest wealth creators in the fund industry, the list was dominated by the biggest fund families, including Vanguard and Fidelity. This reflects a positive feedback loop of size and performance: Strong performance attracts more assets, which in turn means the biggest fund shops have the most impact on wealth creation in dollar terms. Not surprisingly, most of the firms that have destroyed shareholder value are on the smaller end of the fund industry based on asset size. Credit Suisse, for example, is a giant in the world of Swiss banking but a relatively small player in the fund industry.

In most cases, the fortunes of the worst-performing fund families are a product of their investment focus. Many of the firms on our list have lineups that are heavy on specialized and volatile categories, such as commodities, natural resources, and emerging markets—areas that failed to enhance shareholder value during most of the decade covered in our study. Credit Suisse, Global X, Amplify, and ALPS are a few examples of this trend. Direxion’s focus on inverse and leveraged ETFs also led to wealth destruction over the period covered in our study.

ARK, which attracted a stunning US$20.6 billion in estimated inflows in 2021 thanks to eye-popping returns for its flagship ARK Innovation ETF ARKK the previous year, is also worth mentioning. As a whole, the ARK family lost an estimated US$1.3 billion in shareholder value over the 10-year period—even before its funds posted losses ranging from 28% to 61% for the year to date through Dec. 2, 2022. ARK’s value destruction over the 10-year period mainly reflects heavy losses during 2021 for two funds: ARK Genomic Revolution ETF ARKG and ARK Fintech Innovation ETF ARKF.

The worst value destroyers by Morningstar Category are a hodgepodge of highly volatile and specialized categories. Two of them—energy limited partnership and commodities broad basket—have fared better so far this year thanks to soaring energy prices and resurgent inflation. But the remaining categories have little investment merit. For example, our study revealed that trading-inverse equity funds destroyed an estimated $46.9 billion over the trailing 10-year period. These funds occasionally rise to the top by betting against the market; for example, most funds that bet against U.S. stocks are up 20% or more so far in 2022. But because market returns are positive more often than not, the long-term results haven’t been pretty.

Conclusion

The biggest value destroyers in the fund industry illustrate that there’s no guarantee of success, even during a generally favorable market environment. They also provide a valuable case study in how not to invest. (As Charlie Munger is fond of saying: invert, always invert.) Investors have been far better served by the plain-vanilla fund categories that dominated the winners list, such as large-cap blend, allocation—50% to 70% equity, and foreign large blend. They’ve also generally fared well by sticking with the industry’s biggest and most established fund families. Volatile and speculative categories—as well as small, unproven fund shops—on the other hand, are best avoided.