I don’t know about all of you, but every single person I’ve ever spoken to has dreamt about winning the lottery. Last week in Toronto, a $70 million ticket went unclaimed after being awarded a year ago. Other actually claimed their winnings, like Redditor u/Ok_Manner_3333.

The original poster (OP) asked r/PersonalFinanceCanada about what to do with their winnings from playing the lottery. They said they won playing a scratch ticket, and have the option of receiving $710 per month for life or $232,000 lump sum. They wanted to know which to choose, and why. Canadian Reddit users were nearly unanimous in their advice to take the lump sum – though some recommended real estate, gold, and bitcoin. Here are some of the responses:

Reddit Canada on Lump Sum Vs Monthly Payments

Determine the actual lifetime amount total (usually a certain number of years) and then consider the time-value of the money and what will be more financially beneficial and beneficial for your life (like if you can buy property now and want to). Often lump sum will come out ahead.

u/Tack

Without doing any math I know I'd take the lump sum. This way the money is there to leave to family incase something happens to me. I doubt those lifetime prizes can be transferred.

u/sweetsal99

Buy Bitcoin before we go poor forever

u/JoeYo743

90%+ of these cases, the lump sum is better. The depreciation of value over time is too great, and you never know what might happen throughout the years. These lottery organizations pretty much expect you to die halfway down the line so they can cease the monthly payouts.

u/IntergalacticBurn

Do not take the monthly, that money will depreciate fast due to inflation. Take the 200k of the money and give it to a financial advisor to invest for long term. Use the rest for yourself.

u/predator_handshake

Lump sum all day. Just chill with for a year and figure it out slowly.

u/Background_Panda_187

Morningstar Runs the Numbers on Reddit User’s Lottery Winnings

We asked Morningstar director of investment research Ian Tam to run the numbers for the OP. Here’s what he said:

Congrats on the win! What you haven’t told us is when you’re going to need the money. This is an important consideration because it may open up (or restrict) the types of investments you can put your prize money in. There is a wide spectrum of products between a GIC and an S&P 500 ETF. Maybe there’s something in between that might fit your needs better. For now, we’ll assume that you leave the money untouched in both scenarios.

Given that you’re trying to compare the relative value of two investments, we won’t factor in inflation into the calculation, so the results are in today’s dollars, which will likely buy you less in the future, so keep in mind if you plan to solely rely on this as your nest egg. All this said, here’s what the returns would have looked like had you won the lottery about 20 years ago, to add perspective:

As you know, the returns of stocks are far from guaranteed. In fact, had you invested in U.S. stocks initially, you would have underperformed the GIC over the first 8 years of the investment timeframe. It is at this point that most investors begin to question their choices. However, staying invested would have paid off eventually, in spades. This emphasizes the need to ensure you have an idea of your investment time horizon.

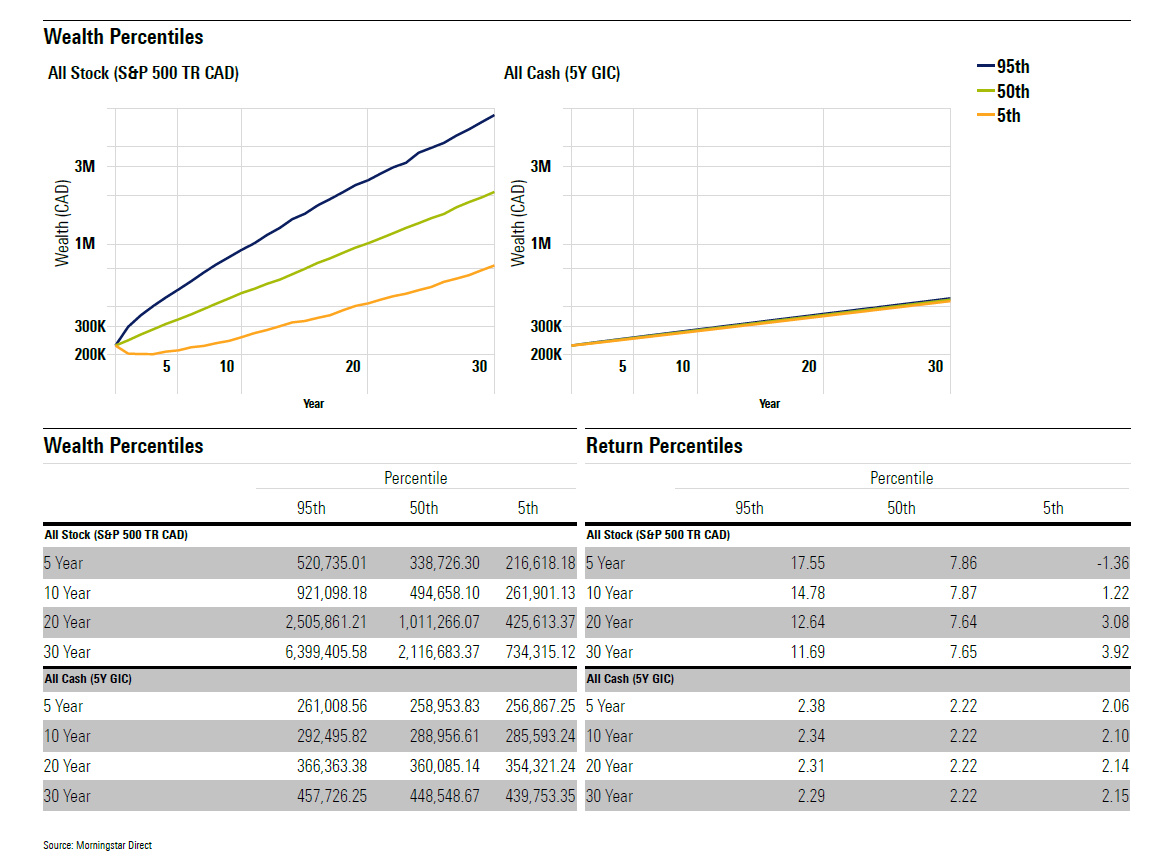

Clearly, we don’t know if the S&P500 will continue to perform well over the next few years. However, we can use methods like Monte Carlo simulations to help visualize different scenarios. In a Monte Carlo simulation, we use random sampling to approximate the behavior of a complex system or process. It involves generating a large number of random inputs and using them as inputs for the system or process being simulated. In the above case, we use it to predict what the returns of both a five-year GIC and the S&P 500 index would be across 2000 simulations, on a starting portfolio of CAD $232K . We then order the results and summarize what would happen in a really good scenario (95th percentile) a worst-case scenario (5th percentile) or somewhere in the middle (50th percentile).

In the above result (which was generated using the Asset Allocation module in Morningstar Direct), we see that indeed over a long time frame over multiple simulations, it’s likely that the 5Y GIC is going to be left behind in the dust. However, over shorter time frames and with an unlucky roll of the dice, it’s very possible that the stock investment underperforms the GIC over 5 or even 10 years.

Finally, to answer your question around lump sum versus a payment plan, here’s the math assuming you invest at a 5% annualized return rate in both the $232K lump sum and $710 a month scenario.

Given the option and all things equal, a logical investor would prefer to take the lump sum investment such that they can take advantage of compounding returns early on.

How to Invest Lump Sum Earnings?

Apart from winning the lottery, there are other ways in which you could come into money including inheritance, legal settlements from divorce, insurance payouts, sale of businesses, legal settlement from injuries, or earnings from stock market investments.

If you do come into some money, here are five check points to managing a financial windfall:

- Stay Calm and Plan: As always, it helps to have a plan, and then stick to it. A 2018 BMO report showed that before receiving a financial windfall, retirement planning, increasing and protecting wealth and managing taxes were some of the top financial goals that respondents had. However, on imagining a windfall, these goals changed to debt reduction, sharing with family, friends and charity, and investing in stocks, among others. Whatever you want to do, have a plan first.

- Proceed According to the Plan: It is important that no matter how much money you have or don’t have, you save according to financial goals. Morningstar director of personal finance Christine Benz points out that setting financial priorities and delaying gratification today in favor of greater rewards at a later date is a challenge that will be with us throughout our lives.

- Pay Off High-Interest Debts: If you have high-interest-rate credit card or student loan debt, the best return on your money is apt to be paying back the money. “After all, you'd be hard-pressed to find a guaranteed return on an actual investment that exceeds the interest you're paying to service the debt,” Benz says. However, if you have loans that are covered by insurance, they could be put lower on the list of priorities.

- Taxes: Lottery winnings in Canada are not taxable. Neither is a life insurance payout to a beneficiary. Inheritances are generally not taxable either. However, there are income tax consequences on bequeathing property. Make Sure you have your tax situation sorted out.

- Get Help – If You Need It: “If your windfall represents a large sum - to you, if not in absolute terms - seek out professional advice about what to do with it,” Benz says. She points out that if your questions are largely tax-related, a CPA is likely your best resource; if you have questions about both investing and taxes, a financial planner should be able to address your concerns.

Once you have this in place, how should you invest? Dollar cost averaging – or investing a little at a time – or lump sum? This is a controversial opinion: Morningstar believes that dollar cost averaging doesn’t work – a lump sum investment is always better.

Dollar Cost Averaging Doesn’t Work

For investors, there are fewer more nerve-wracking moments than deciding how to invest a big cash windfall, the kind that might come from the sale of a business, an inheritance, or a hefty bonus. The instinct among many individual investors is often to gravitate toward dollar-cost averaging, or DCA. Deciding to invest a lump sum into the markets is easily accompanied by a parallel fear: “What if the market crashes tomorrow?” Or next week? Or even next year? The reality is that nobody knows what the market will do tomorrow, next week, or next year.

In their paper, “Dollar-Cost Averaging: Truth and Fiction,” Morningstar’s Maciej Kowara and Paul Kaplan show that historically, DCA has produced lower long-term returns than lump sum investing, or LSI. At the same time, the returns from DCA are more uncertain than the results from LSI – when it comes to meeting an investment goal, this could mean greater risk.

Kowara and Kaplan calculated the results of LSI over all two-, three-, four-, up to 120- month periods and compare them against the final wealth achieved by spreading out the total investment into monthly segments over those periods. They then calculated the percentage of cases in which DCA resulted in more wealth than LSI for each time span.

The results: When you look over the average 10-year time frame, nine out of 10 times, an investor who dribbled money into the market would have ended up with less money than if they had simply put all their money into the markets at the beginning.

Of course, long-term averages hide the bumps. What if an investor were handed a $100,000 check in June 2008, just as the global financial crisis was about to break out? Wouldn’t it be better to have done DCA then, and captured the lower prices? Even in 2008, LSI would have been the better choice. Despite the massive haircut taken to the investment in 2008, it isn’t hard to understand the reason for the outperformance of the LSI approach: since hitting bottom in early 2009, the U.S. stock market has been in in an uninterrupted bull market ever since. What about investors who got a windfall in June 2009, but – shell-shocked from the financial crisis meltdown – dribbled in their money, instead of putting it to work all at once? They would have been left far behind by the bull market in stocks.

The fundamental problem with DCA is that it is a market-timing strategy. Holding money back and then investing it later only makes sense if investors believe that the prices of the securities they are planning to buy will fall for a while and then eventually rise.

As it is unlikely that many investors are making such forecasts, most investors should not be following a DCA strategy.

This article does not constitute financial advice. It is always recommended to conduct one’s own research before buying/selling any security.