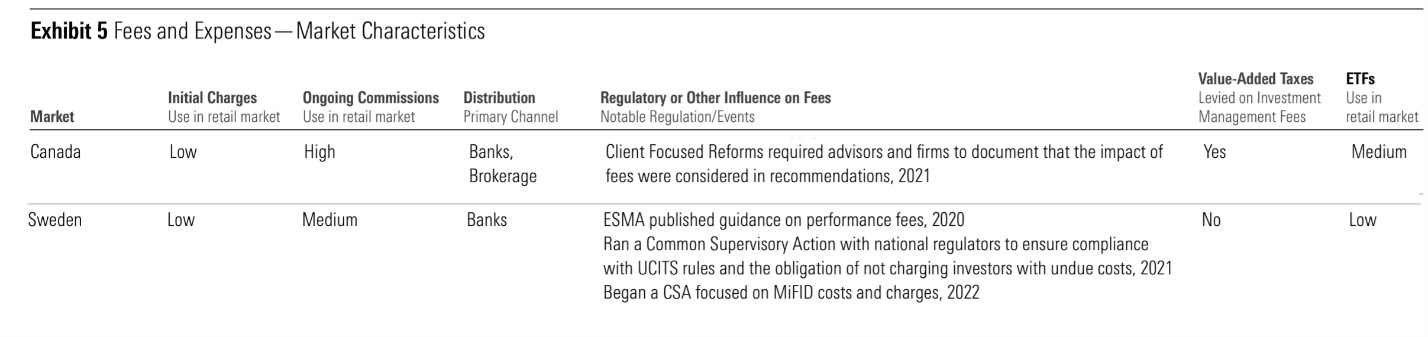

Recently my colleague Johanna Englund wrote about the performance of some of the most expensive Swedish-domiciled funds. According to her article, and Morningstar’s own Global Investor Experience, Swedish investors are privy to a favourable low-fee environment for investors. Interestingly enough, Sweden and Canada share some common characteristics, including the fact that the main distribution network for investment funds is via bank channels and low use of initial charges (i.e., flat fees charged by advisors up front for buying a mutual fund).

Source: Morningstar Global Investor Experience: Fees & Expenses Report

In her article, Johanna analyzed the top 10 most expensive Swedish mutual funds to reconfirm a message well-known to experienced investors: most of the time (not always), expensive funds do not do an investor any favours over time.

High Fees Hurt

Fees detract consistently from the amount of ending wealth an investor has, a fact that is reflected in Morningstar’s fund ratings on both a backward-looking (star ratings) and forward-looking (medalist ratings) basis.

Today, I use Morningstar’s fee-level methodology to provide a cross-section of fees against performance in the Canadian market. Canadian retail investors are offered mutual funds in two ways: (1) via commission-based advice channels where fund fees include the cost of advice or (2) via fee-based share classes where advice fees are charged separately, or not charged at all if purchased through a discount brokerage (ETFs are also sold in this manner, without embedded advice fees). In most cases, Canadian-domiciled mutual funds are offered both ways.

The Morningstar fee-level methodology groups mutual funds into similar category groups and ranks fees against these groups. The most expensive quintile (or top 1/5th of funds) receive a ‘high’ rating, the next most expensive quintile receives “above average” and so on. The methodology considers the distribution channel as well, ensuring that funds with bundled fees are only compared against others of similar nature. For today’s study, we isolate only fee-based share classes to remove the effect of fee-bundling.

The above chart compares the fee level against the Morningstar Rating for Funds (informally known as the “star rating” which is a backward-looking assessment of funds’ after-fee performance against peers on a risk-adjusted basis). The chart also reveals some interesting insights. Among 5-star rated funds, 12% have 'high' fees while 25% have low fees. In contrast, 27% of 2-star funds have high fees, and only 16% have low fees. Notably, as we move down the rating scale (excluding 1-star funds, which are still directionally similar), the proportion of high-fee products increases, and the percentage of low-fee funds decreases.

This data suggests that although not all higher-fee funds underperform their category peers, a minority of them do. On the other hand, a higher proportion of low-fee funds tend to outperform their peers.

The above table shows the most expensive fee-based mutual funds and includes each funds’ Management Expense Ratio (MER), which is not paid explicitly by the investor but instead is subtracted from yearly returns. Clearly, the minority of the most expensive funds have outperformed their category peers (as denoted by the star rating), though it is not impossible – particularly in the case of Picton Mahoney’s Fortified Income Fund and CI’s Precious Metals Fund, neither of which should make up a substantial portion of a typical Canadian investor’s asset allocation. The remaining funds, most of which invest in equities, have underperformed category peers.

The lesson in all of this is one that Morningstar has told time and time again – fees are not the only thing that one should consider when investing in a mutual fund, but it should be a major consideration given the effect they have on wealth over time.

This article does not constitute financial advice. It is recommended to conduct one’s own independent research before buying or selling any of the investment funds listed here.