I recently discussed a radio personality’s recommendation that retirees spend 8% each year from their investment portfolios. Those withdrawals would be inflation-adjusted. To accomplish that mission, he stated, investors should place 100% of their assets in equities.

The suggestion should be regarded as performance art rather than actual advice. Even if the speaker’s counsel had been supported by solid research—which it assuredly was not—few retirees would adopt that plan. It doesn’t take a Nobel Prize to realize that the bankrupt 75-year-olds do not make financial comebacks.

History’s Verdict

His comments, however, lead to an interesting question. If previous retirees had attempted such a strategy, how would they have fared? The short version is that I evaluated 68 rolling 30-year periods, determining the fate of equity portfolios that used 8% real withdrawal rates.

In 45% of the trials, the portfolio did not withstand the scheduled disbursements. Once in every three attempts, it was exhausted by year 20. One could, I suppose, paint the pig by pointing out that 8% withdrawals succeeded more often than not. The same, regrettably, may be said for a round of Russian roulette.

This strategy is ill-suited for most newly minted retirees, as their time horizons are too long. For example, a 65-year-old nonsmoking male with average health has a 25% chance of surviving 27 years. (For women of the same age, the figure is 29 years.) Spending aggressively can make sense for older retirees who have relatively short life expectancies, but it is not appropriate for those in their 60s.

Don’t Start Slowly!

Perhaps, though, one could apply the strategy flexibly. That is, rather than automatically withdrawing the same inflation-adjusted amount—assuming a 3% inflation rate, withdraw $40,000 from a $500,000 portfolio in year 1, $41,200 in year 2, $42,436 in year 3, and so forth—adjust spending according to the stock market’s results. If equities perform well, stay on track. If they do not, pull back.

Supporting that logic is a calculation from the previous column. In that article, I computed the median stock market return during the initial year of retirement for 1) the portfolios that survived until year 20 and 2) those that did not. The results were, respectively, 11.1% and 0—a very large difference! Indirectly, those results suggest that retiree portfolios fare best when they start strongly.

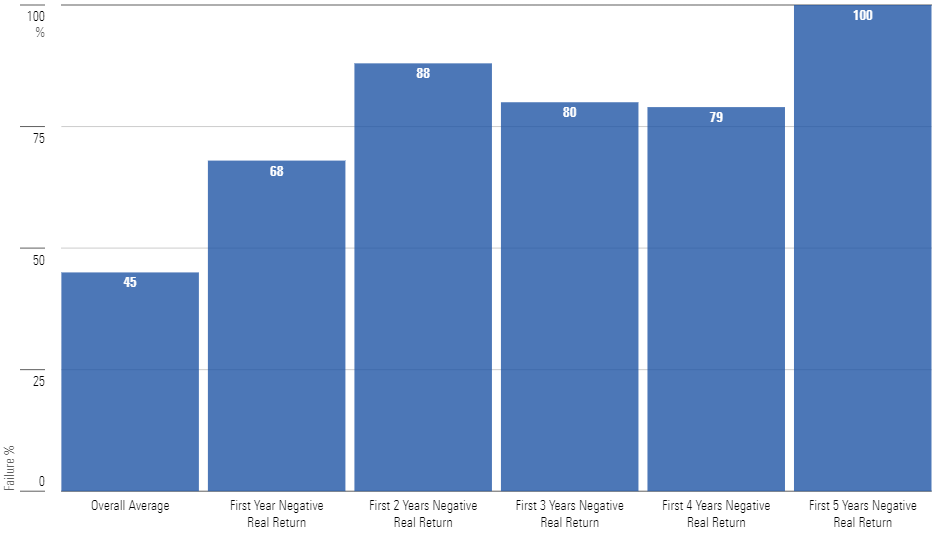

That is indeed the case. For reasons I have discussed elsewhere, returns that occur early during retirement are much more important than the later arrivals. The chart below demonstrates that precept. It shows the portfolio failure rates, over 30 years, for all trials of the 8% withdrawal rate during which the first year’s return was negative, after considering the effect of inflation. It repeats the exercise for the cumulative results over the initial two-, three-, four-, and five-year periods.

Failure Percentages With an 8% Real Withdrawal Rate

(100% Equity Portfolio, 30-Year Holding Period)

The picture tells a grim story. Withdrawing an inflation-adjusted 8% from an equity portfolio is perilous at the best of times, but outright destructive for portfolios that start poorly. Such strategies misfire two thirds of the time if the first year’s return is negative (again, after accounting for inflation). It only gets worse from there. By year 5, there’s no hope. No portfolio that suffered real losses through its initial five years survived the full three decades.

Withdrawal-Rate Cuts

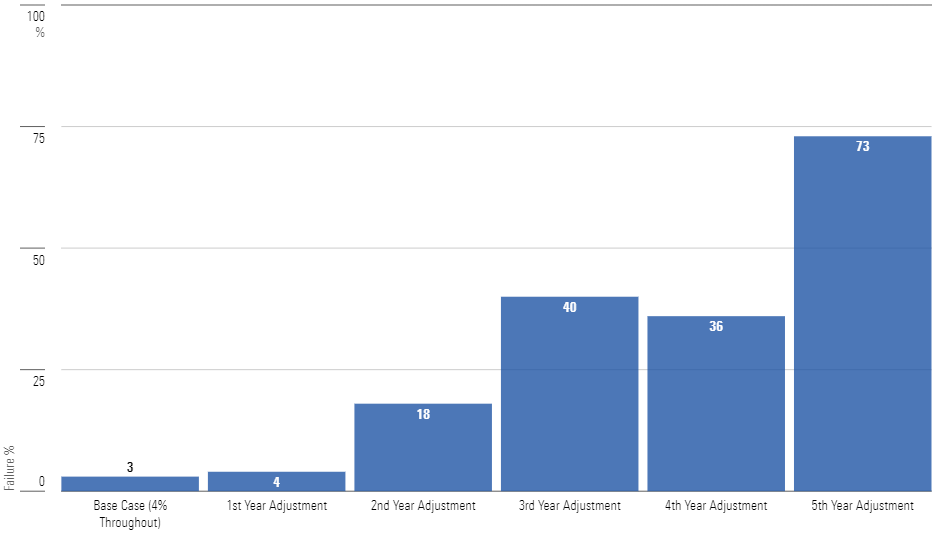

What about starting aggressively with a high spending rate, then backtracking if necessary? For this article, I evaluated a simple, if unsophisticated, investment policy. Begin with an 8% withdrawal rate, per the radio host’s recommendation. If the portfolio’s real returns are negative after any of the first five years, switch to an annual withdrawal rate of 4%. Once at 4%, stay there.

I designed this arrangement to instruct, not advise. Halving one’s portfolio-withdrawal rate forever, based on an arbitrary performance rule, would be silly. But the exercise should provide at least some indication of the power of on-the-fly spending adjustments. Are such changes effective? Do they meaningfully affect portfolio survival rates? Or do they come too little, too late?

The next chart answers those questions. As the long title and subhead suggest, it is a bit tricky to explain, so bear with me. The left bar shows the failure rate, over 30 years, for portfolios that used a steady 4% withdrawal rate. (To reiterate, these are the historical figures. When looking forward, Morningstar calculates different future odds.) It represents the conventional case. The remaining bars show the failure rates for portfolios that start with 8% withdrawal rates, then retreat to 4% after they suffer negative real returns.

Failure Percentages With an 8% Real Withdrawal Rate and Adjusting for Slow Starts

(100% Equity Portfolio, Initial 8% Real Withdrawal Rate, Adjusted Rate of 4%, 30-Year Holding Period)

Incorporating the adjustment fixes the year 1 problem. Retirees who spend ambitiously during their initial 12 months but then back down if that portfolio loses money in real terms are barely worse off than those who used a 4% withdrawal rate from the beginning. But the news sharply worsens if the two-year results are negative. And from year 3 onward, it is unpalatably bad.

Wrapping Up

The conclusions are inescapable.

1) An 8% real withdrawal rate from an equity portfolio can persist through several decades. Retirees who are fortunate enough to ride an early bull market will likely be able to maintain such a high spending rate.

2) But how to know in advance? Bull markets appear only in hindsight.

3) Although it’s possible to withdraw flexibly, by scampering to safety if stocks perform poorly, there’s little room for error. In nearly one observation in five, a mere two years’ worth of investment results doomed one portfolio in five, even after the real withdrawal rate was slashed to 4%.

Beginning one’s retirement with a 5% withdrawal rate and the willingness to adjust is reasonable. Perhaps even 6%. After that, not so much. My suggestion: Don’t try that at home.

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MNPB4CP64NCNLA3MTELE3ISLRY.jpg)