:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/K37XP2B425AIRFXOASS7WIGPLM.jpg)

Step into a time machine and travel 30 years back, to March 1, 1994. Emerging-markets stock funds have become the exciting new investment, and mutual funds the way to own them. For a small annual fee, investors can participate in the rapid growth of such countries, while diversifying their risks among dozens of holdings and benefiting from professional management. What an opportunity!

One thing was for certain: Better stocks than bonds. Sure, emerging-markets bonds figured to outgain their domestic counterparts because greater risk eventually creates greater rewards, but when investing in high-growth areas, why buy debt? After all, nobody ever got rich buying bonds from Walmart WMT or Microsoft MSFT. The path to riches comes from ownership, not lending.

The Reality

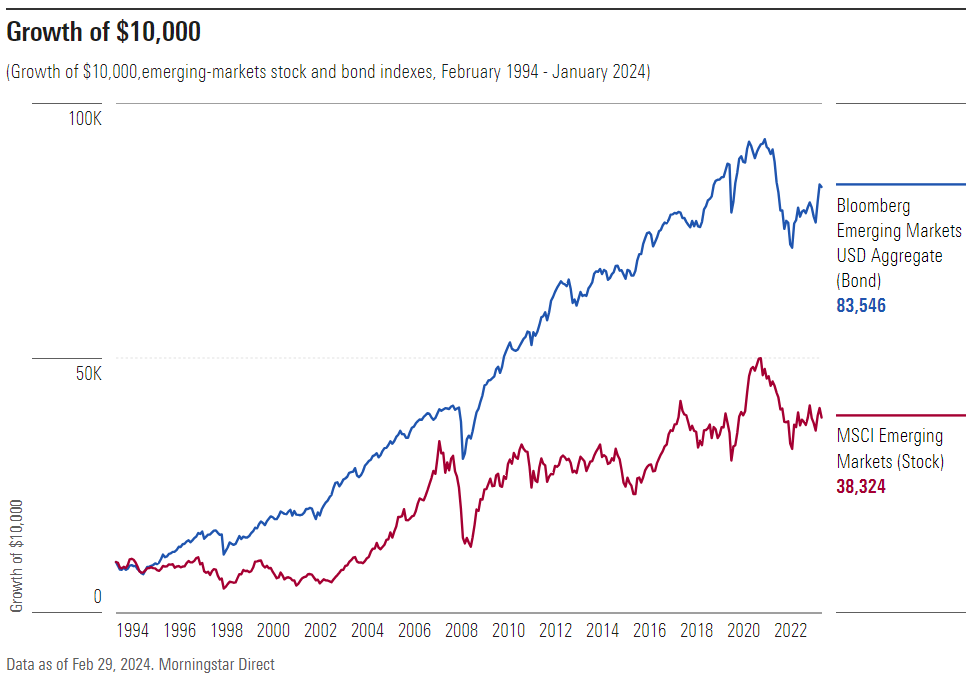

Or so the theory went. The practice was very, very different. Below are the 30-year returns, since February 1994, for 1) MSCI Emerging Markets Index, which contains stocks, and 2) Bloomberg Emerging Markets USD Aggregate Index, which holds bonds. The Bloomberg index appears in blue and MSCI in red.

Well now. As you may have heard in modern US history, bonds have never outgained equities over any 30-year period. (That statement does not apply for the nation’s earlier history, though.) But they certainly have done so with emerging markets. Bonds started off ahead, conceded some of their lead in the mid-2000s, recovered their lost ground in 2008, and have not since looked back.

During the 30-year period, the annualized total return for Bloomberg’s bond index was 7.33%, as opposed to 4.58% for MSCI’s stock index. So much for the equity risk premium! The contest was not even close. Through the 30 years, bonds triumphed by a whopping 2.75 percentage points per year.

The Dollar’s Effect

One potential explanation for this anomaly is the strength of the US dollar. Although the business press has long bemoaned America’s “weak dollar” policy—a habit that reached its apex when The Wall Street Journal praised Heidi Klum for choosing to be paid in euros rather than dollars—their forecasts have, in fact, been grievously wrong. Last year, the U.S. Dollar Index reached a 20-year-high.

That matters because emerging-markets bonds have historically been denominated primarily in dollars. Through the early 2000s, almost all foreign-held debt from emerging nations consisted of US dollar bonds. That percentage has since declined to about 60%, but nonetheless, emerging-markets debt has largely been protected against the dollar’s rise. Not so for its equity rivals.

That condition, however, only accounts for about 1 percentage point of the annualized performance gap, which still leaves emerging-markets stocks well behind their fixed-income rivals. To that handicap may be added the International Monetary Fund’s assessment that a strong dollar slows the relative growth of emerging-markets economies by reducing their trade volumes and squeezing credit. That may have cost emerging-markets stocks a further percentage point.

Economic Booms

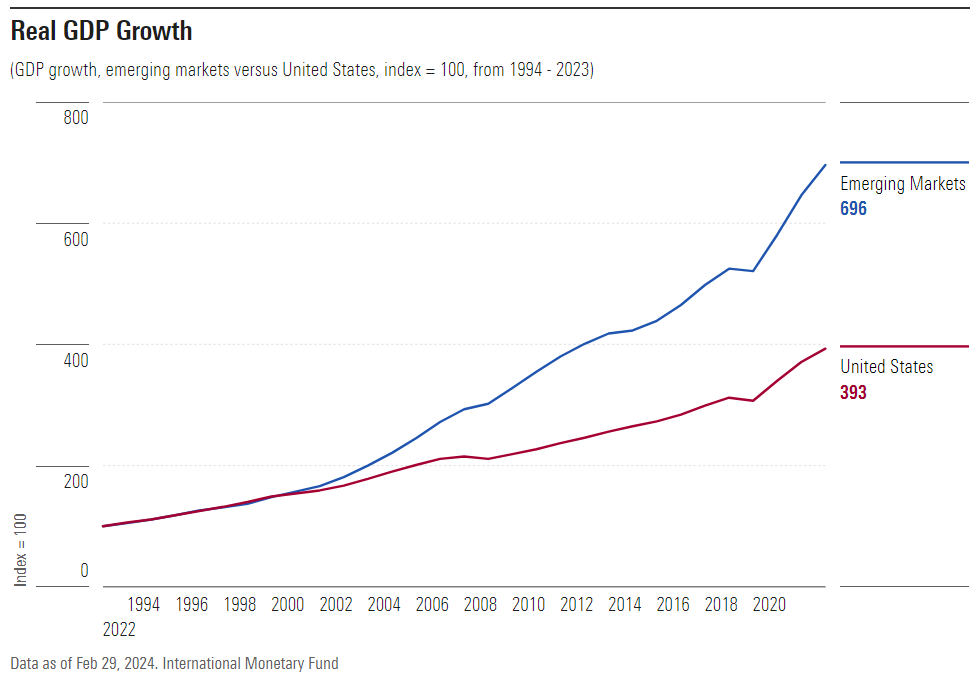

Of course, the dollar’s strength notwithstanding, most of the emerging markets have handsomely expanded their economies. According to the IMF’s data, real gross domestic product growth for the emerging markets has substantially exceeded that of the United States since 1993, even when converting those figures into dollars.

Admittedly, this comparison is incomplete because it ignores population changes. As the emerging markets have increased their populations more rapidly than has the United States, they could conceivably have posted faster GDP growth while not improving individual productivity. That, however, has not been the case. When scored by GDP per capita, the emerging markets have been superior. No matter what the measurement, they have delivered on the promise that equity investors so dearly prized 30 years ago: speedier economic growth.

Considering Valuations

A final potential explanation for the struggles of emerging-markets stocks is lower valuations. If emerging-markets equities were costly in 1994 and have since become cheap, that markdown could have sharply affected their returns.

That process did occur, but only mildly. In 1994, reports the investment-management firm Schroders SDR, the price/earnings ratio for emerging-markets stocks, based on the next 12 months’ forecasted results, was 16. Today, that figure is 12. That effect, once again, amounts to about 1 percentage point a year.

The Postmortem

Over the past 30 years, emerging-markets stocks have shed an annual percentage point of performance to each of three items: 1) direct currency losses, 2) indirect currency headwinds, and 3) reduced investment valuations. In aggregate, those factors account for the discrepancy between emerging-markets stocks and bonds. Had they not occurred, returns for the two asset classes would have been similar.

Which leaves us with a mystery. Stocks are supposed to outgain bonds over three decades, particularly when their economies, as represented by GDP growth rates, have been outstanding. So, as well, has been the political news. By and large, the major emerging markets have been war-free, with stable governments. The conditions have been seemingly ideal—yet even when appraised generously, the equities from those countries have not been able to beat bonds. What happened?

That question I cannot fully answer. I will offer two partial responses, though. First, emerging-markets companies are better at booking revenues than profits. A few years ago, McKinsey & Company estimated that returns on invested capital were 50% higher for North American businesses than for their emerging-markets competitors. Second, honesty pays with investing. In general, countries that score well on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index have enjoyed higher stock market returns. Few of those nations are emerging.

Looking Forward

History may not repeat. The dollar could weaken, the price/earnings ratios for emerging-markets stocks could rise, and profit margins could strengthen. For those reasons and more, many investment forecasters now expect emerging-markets stocks to outgain their developed-market rivals. Perhaps. Unfortunately, such claims are not new. For many years now, emerging-markets optimists have issued such prophecies. They have yet to transpire.

Eventually, emerging-markets equities will recover from their funk. Whether that makes the asset class worth owning is, however, another story. I remain skeptical.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. This article was originally published on Morningstar.com for a U.S. audience.

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/A6OOX7PBSVEJ5BXDFSPKGLO72M.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VYKWT2BHIZFVLEWUKAUIBGNAH4.jpg)