:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MCOHMFJ2MVEVPAJNB73ASRA4EA.jpg)

Wondering what's in store for interest rates?

Since July 2023, the US Federal Reserve has kept the federal-funds rate at a target range of 5.25% to 5.50%, far above typical levels over the past decade. But we expect Fed officials to deliver hefty cuts over the next two to three years and bring the federal-funds rate to 1.75% to 2.00% by year-end 2026.

In our latest Economic Outlook, we detail that downward trends in inflation will make this pivot possible. Slowing gross domestic product growth (and a slight rise in unemployment) in 2024 will further increase the chances of the Fed cutting sooner rather than later.

We expect inflation in 2025 and 2026 to come in below the Fed's 2% target and unemployment to remain slightly elevated (above 4%) until 2027, which should induce continued cuts until the federal-funds rate is just under 2%. Our long-run expectation for the 10-year Treasury yield is 2.75%, significantly below the current yield of 4.20% as of July 2024.

Why Did the Federal Reserve Hike Up Interest Rates in 2022 and 2023?

Since 2022, the Fed has been engaged in an all-out struggle against high inflation.

From March 2022 to July 2023, the Fed increased the federal-funds rate by 5 percentage points, marking the largest and fastest rate hike in 40 years. The Fed has also engaged in "quantitative tightening" – selling off about $1.7 trillion (£1.3 trillion) from its long-term securities portfolio since June 2022.

The United States (as many other countries) experienced a decade of low interest rates after the 2008 global financial crisis and the great recession.

The 10-year Treasury yield averaged 2.4% from 2010 to 2019, compared with 4.2% today. The federal-funds rate was near zero much of the time, averaging 0.6% from 2010 to 2019. We did see interest rates tick up in the prepandemic years but only slightly (the 10-year averaged 2.5% from 2017 to 2019, and the federal-funds rate averaged 1.7%).

How the Economy Has Responded to Higher Interest Rates

Now with interest rates reaching levels not seen since the mid-2000s, many are wondering whether we've shifted to a new regime of higher interest rates.

Higher interest rates have meant higher borrowing costs for consumers and businesses.

• The 30-year mortgage rate stands at about 6.9% as of July 2024, a massive jump compared with the 3.0% average in 2021 and far above the 4.2% average in the prepandemic years (2017 to 2019).

• Mortgage rates reached a high of 7.8% in November 2023, the highest in over 20 years.

Higher interest rates are designed to slow down spending in interest-rate-sensitive sectors like housing. This cools off the broader economy, helping achieve the Fed's goal of reducing inflation.

Yet, the US economy proved more resilient to the impact of higher rates than expected in 2023. Widespread fears of a recession did not play out. Housing activity fell sharply, but much of the rest of the economy has been unscathed.

The impact of the surge in the federal-funds rate has also been somewhat cushioned by the inversion of the yield curve, where short-term bond rates (such as the fed-funds rate) are higher than long-term bond rates (such as the 10-year Treasury yield).

Recall that the fed-funds rate is under the direct control of the Federal Reserve, allowing the Fed to control short-term risk-free interest rates. Longer-run interest rates are influenced by the Fed but only indirectly.

Contrary to much commentary in the financial press, yield-curve inversion is not contractionary. There is a historical correlation between yield-curve inversions and recessions, but the statistical significance is weak using cross-country evidence.

From a causal perspective, an inverted yield curve actually stimulates the economy compared with a flat yield curve (holding short rates fixed) because it means lower borrowing rates on long-term debt. Because the yield curve has inverted so much, the Fed has been forced to hike the federal-funds rate more than it would have otherwise to sufficiently cool off the economy.

Of course, even while the Fed failed to cool down the demand side of the economy in 2023 very much, inflation ended up falling anyway because of supply-side improvement, which is unrelated to monetary policy.

When Will the Fed Lower Interest Rates?

We expect the Fed to start cutting rates beginning with the Federal Open Market Committee's September 2024 meeting.

The Fed will pivot to monetary easing as inflation falls back to its 2% target and the need to shore up economic growth becomes a top concern.

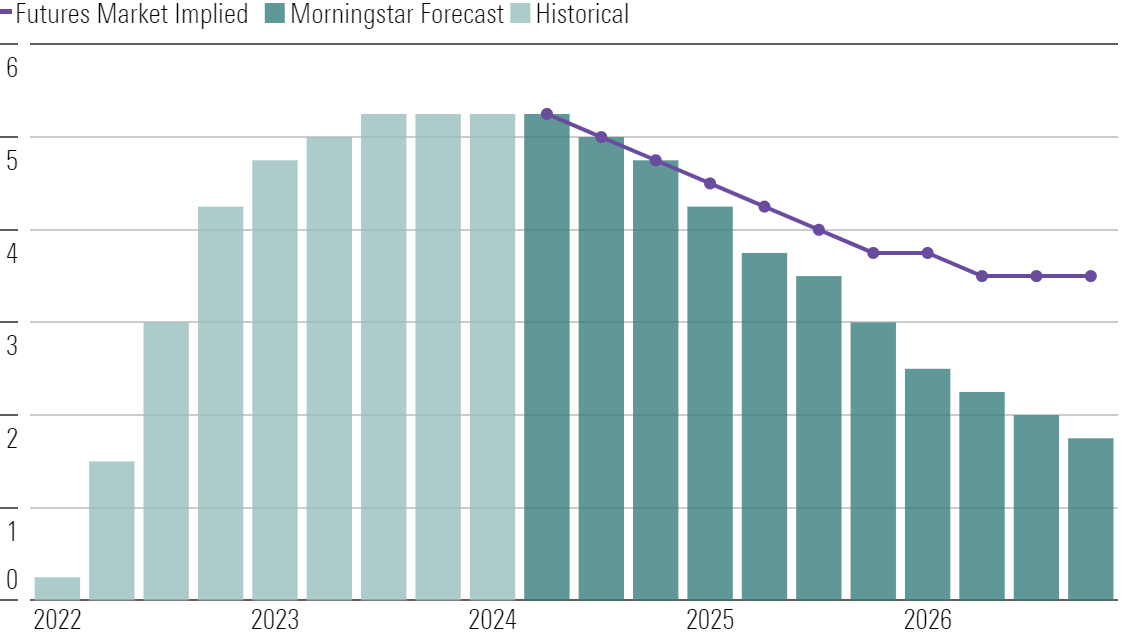

1. Interest-rate forecast. We project the federal-funds rate target range to fall from 5.25% to 5.50% currently to 4.75%-5.00% at the end of 2024, 3.00%-3.25% at the end of 2025, and 1.75%-2.00% by the end of 2026, after which the Fed will be done cutting. Likewise, we expect the 10-year Treasury yield to move down to an average of 2.75% in 2027 from its current yield of 4.20%. We expect the 30-year mortgage rate to fall to 4.25% in 2027 from an average of 6.80% in 2023.

2. Inflation forecast. It looks like inflation will return to normal without a recession. We expect inflation to fall from 3.7% in 2023 to 2.4% in 2024 and an average rate of 1.8% over 2025-28, dipping slightly below the Fed's 2.0% target. The continual downtrend in inflation will be owed greatly to the unwinding of price spikes as supply constraints ease and as the pace of economic growth slows.

Inflation reports showing falling rates over the past year have defied the predictions of those in the stagflation camp, who thought that a deep economic slump would be needed to eradicate entrenched inflation. Instead, the inflation-GDP trade-off has been very kind.

Admittedly, this timing of rate cuts is slightly delayed compared with our previous expectation that the first cut would happen in the first quarter of 2024.

But an uptick in inflation in January and February, along with a lingering hawkish bias by the Fed, ruled out cuts in the first half of the year. Although the odds depend on Fed members’ own subjective assessment of whether progress on inflation is sufficient to begin cutting rates, we think the inflation data will progress sufficiently to allow cutting before the end of 2024, which is why we expect the first cut in September 2024.

As long as the Fed is allowed to shift to easing in 2024, GDP should avoid a large downturn and start to accelerate in 2025 and 2026.

Housing is the most interest-rate-sensitive major component of the GDP, and we expect another 6% drop in housing starts in 2024. Higher mortgage rates combined with the earlier surge in housing prices mean that home affordability is at its worst since 2007. Lower mortgages will be needed to avert a deeper and prolonged downturn in the housing market.

Why Do We Disagree with Other Investors (and the Fed's Signals) on Interest-Rate Forecasts?

The nearly unanimous view now is that the Fed is done hiking rates, but there's still much debate about when and how much it will cut.

We diverge from the market by expecting significantly more cutting. By the end of 2026, we expect a fed-funds rate around 175 basis points below the market's projection.

Fed-Funds Rate (%) Expectations (Bottom of Target Range)

We believe the Fed will seek to lower rates from currently "restrictive" levels to a more neutral stance once victory over inflation comes into sight. Economic weakness in mid- and late-2024 will push the Fed to pick up the pace. In 2025, inflation will still be below target and unemployment a bit elevated, which will induce further cuts.

We expect inflation to come down quicker than consensus does, which is why we expect the Fed to eventually cut interest rates more aggressively than it currently projects. Likewise, other investors now appear too pessimistic about how quickly inflation will fall.

How Will Fed-Funds Rate Cuts Affect the Economy?

We expect that GDP growth will accelerate in the latter half of 2025 as the Fed pivots to easing, with full-year growth numbers peaking in 2026 and 2027. The resolution of supply constraints should facilitate an acceleration in growth without inflation becoming a concern again.

We expect a cumulative 200 basis points more real GDP growth through 2028 than the consensus does. Consensus remains overly pessimistic on the recovery in the labor supply and has generally overreacted to near-term headwinds, in our view.

How Does Inflation Affect Interest-Rate Projections?

We expect inflation to fall to normal levels after peaking at 6.5% in 2022.

We still think most of the sources of high inflation since the start of the pandemic will abate (and even unwind in impact) over the next few years. This includes energy, autos, and other durables. Still, supply chains are healing as demand normalises and capacity catches up. These factors drove inflation down to 3.8% in 2023, and we expect the rate to fall further to 2.4% in 2024, with an average of 1.9% from 2024 to 2028.

We’re more optimistic about inflation coming down than consensus. We think consensus underrates the deflationary impulse likely to be provided by industries like energy and durable goods in coming years, as pandemic-era disruptions fade.

Where Will Interest Rates Be in 2025 and Beyond?

In the short run from 2024 to 2026, our interest-rate forecast is centered on the Fed’s mission and attempts to smooth out economic cycles. The Fed seeks to minimise the output gap (the deviation of GDP from its maximum sustainable level) while keeping inflation low and stable. When the economy is overheated (that is, the output gap is positive and inflation is high), as today, then the Fed seeks to hike interest rates to slow growth.

But our long-term interest-rate projections are driven more by secular trends than by the Fed.

Instead, interest rates are determined by underlying currents in the economy, like aging demographics, slower productivity growth, and higher economic inequality. These forces have acted to push down interest rates in the United States and other major economies for decades, and they haven't gone away. Regardless of what happens in the next few years, we expect interest rates to ultimately settle back down at the low levels prevailing before the pandemic. The low interest-rate regime will resume once the dust settles from the pandemic's economic volatility.

For this reason, our interest-rate forecast includes the expectation that these rates will stay lower for longer. Even if we're wrong in our near-term view that the Fed's war against inflation will be a short one, our long-term view on interest rates remains valid.

This article was compiled by Emelia Fredlick and Yuyang Zhang

.jpg)