Bargains almost never exist in the stock market. Investors can buy cheap stocks, or they can buy high-quality stocks—those with tremendous profits and fortresslike balance sheets. But those traits rarely coexist.

That means investors face a trade-off. Investing in cheap value stocks usually means forgoing quality, while investing in high quality often requires letting go of cheap valuations. But exchange-traded funds can limit those trade-offs by mixing the two.

Such ETFs can be sorted into four different groups based on the strength of their value and quality characteristics. These groups range from those with wonderful prices (value) to wonderful companies (quality), and combinations of the two.

Wonderful Prices

ETFs holding stocks with “wonderful prices” focus solely on price, or price multiples. Common metrics like price/book value, price/sales, and price/earnings are an imprecise shortcut for a more elaborate discounted cash flow analysis that an active manager may conduct. But precision doesn’t really matter. These ETFs find bargains by holding a broad portfolio of stocks trading at low multiples, implying that they’re cheap relative to their future earnings.

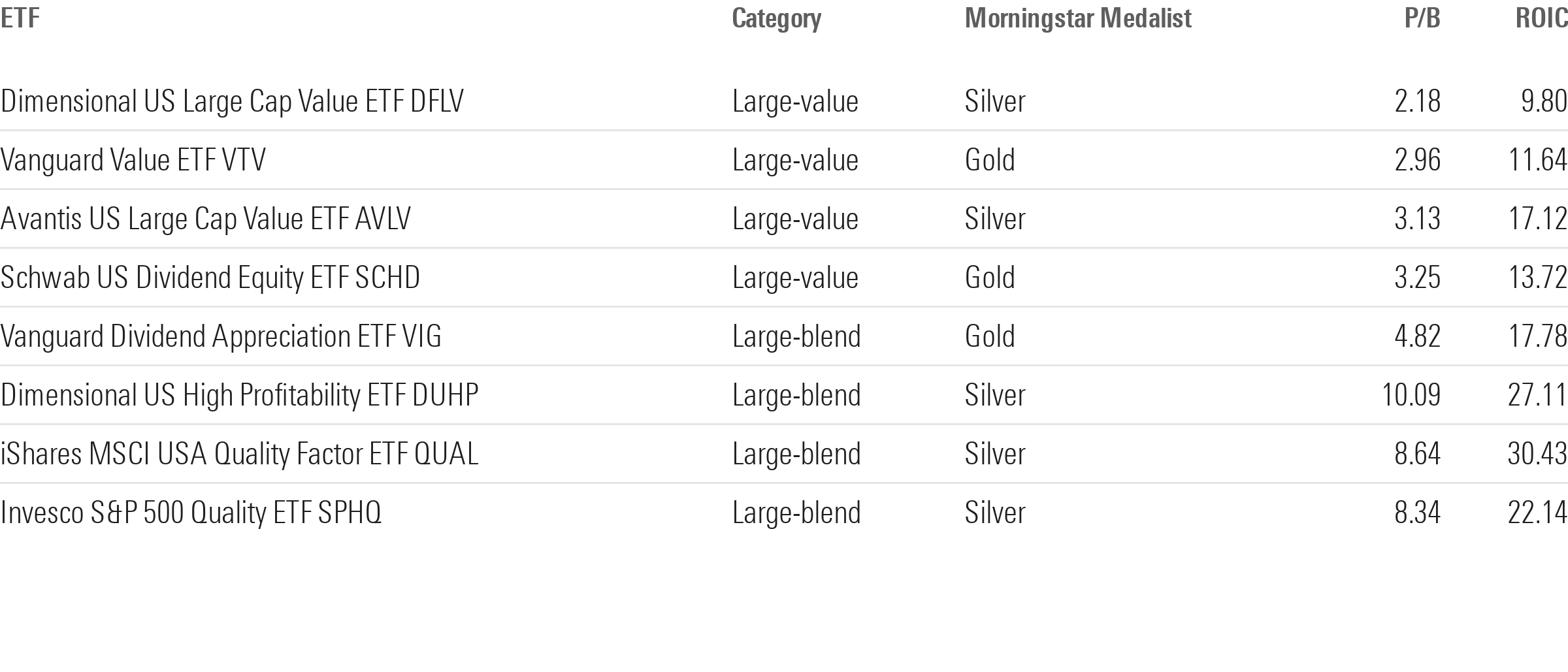

Dimensional US Large Cap Value ETF DFLV (Morningstar Medalist Rating of Silver as of November 2023) is a prime example of a strategy that holds a diverse portfolio of stocks trading at wonderful (cheap) prices. It holds hundreds of stocks that land in the bottom third of the large-cap market by a price/book value ratio. Silver-rated Vanguard Value ETF VTV is similar, but it’s a little broader and holds roughly the cheapest half of the market, so it doesn’t prioritize the cheapest stocks to the same degree as the Dimensional fund. Both ETFs have three main selling points: They’re consistently exposed to the cheapest stocks in the large-cap market, they diversify their portfolios across hundreds of stocks, and they charge relatively low fees.

Cheap prices, on their own, have limits. Stocks with attractive prices in a relative sense (relative to book value, sales, or earnings) may not look attractive in the absolute sense. They might provide meager, if any, future earnings, or their profits may unpredictably fluctuate from year to year. In other words, cheap stocks are often cheap for a reason: They’re risky. That’s usually obvious. For example, the two mentioned above tend to favor cyclical segments of the market such as energy and materials.

Shifting the focus back to fundamentals can help tame some of that risk. The Dimensional fund modestly tips its hat to this idea. It intentionally places more emphasis on the most profitable stocks it holds. That’s an improvement, but the effect isn’t huge. Cheap price multiples still dictate what it holds and how it should perform.

Fair Companies, Wonderful Prices

The second group trades value for a little bit of quality. These ETFs favor cheap stocks but lean toward those with healthier balance sheets and more consistent profits. Examples include Gold-rated Schwab US Dividend Equity ETF SCHD and Silver-rated Avantis US Large Cap Value ETF AVLV.

Shedding ultracheap stocks for some stability comes with costs. The Schwab and Avantis funds will likely miss out on names trading at steep discounts with the most potential to outperform. They also pay up for quality. Both ETFs tend to feature a higher average price multiple than Dimensional US Large Cap Value ETF, and they tend to hold shares in well-established companies that dominate their respective industries. Chevron CVX and Verizon Communications VZ both landed among their top holdings at the end of September.

That’s reasonable. What they lose in potential total return, they make up for by reducing risk. Both tend to have less exposure to cyclical sectors that feature prominently in the Dimensional fund, though that can change when those segments are stable and earn reasonably high profits. For example, Avantis US Large Cap Value ETF’s stake in the energy sector hovered between 15% and 20% over the past several years because many of those stocks were immensely profitable and dirt cheap—a combination that doesn’t come around often.

Wonderful Companies, Fair Prices

The third group puts more focus on quality than value, and the pull is sufficiently strong enough that these ETFs land in the large-blend Morningstar Category. As with the prior group, healthy balance sheets and strong profits usually command a premium. So, incrementally shifting toward those characteristics means incrementally increasing an ETF’s average price multiple. Those higher multiples prevent such funds from landing on the value side of the Morningstar Style Box.

But ETFs in this group don’t agnostically pursue big, profitable stocks for their own sake. They still incorporate valuations into the selection process. These types of portfolios are best described as quality at a reasonable price. Examples include Vanguard Dividend Appreciation ETF VIG and Dimensional US High Profitability ETF DUHP. Both primarily focus on high-quality stocks. Vanguard Dividend Appreciation ETF looks for those that have maintained or increased their dividend payments for 10 consecutive years or longer, while Dimensional US High Profitability ETF simply holds the most profitable stocks in the US market.

Each one also incorporates valuations into its strategy in its own way. The Vanguard fund’s strict dividend criteria means it holds shares in mature businesses that are rarely the subject of speculation. So, its average price multiple tends to hover near that of the broader market. Dimensional US High Profitability ETF takes a more direct route. It simply overweights constituents trading at relatively lower price multiples.

These ETFs should underweight stocks with obnoxious price multiples most of the time. That means they may not always perform well during bull markets, especially when speculative stocks lead the charge. However, they tend to compensate for that shortcoming by performing better when the market slumps. In other words, they may perform like a defensive stock portfolio during periods of intense speculation or sharp declines.

The 18-month period following the coronavirus drawdown exemplified the defensive tendencies of these ETFs. Top-performing stocks like Alphabet GOOGL and Tesla TSLA weren’t tremendously profitable nor did they consistently pay out dividends, so they didn’t qualify for either portfolio. The mutual fund version of Dimensional US High Profitability ETF lagged the Russell 1000 Index by 9 percentage points annualized between April 2020 and October 2021, while Vanguard Dividend Appreciation ETF trailed by 12 percentage points.

Wonderful Companies

The fourth group cranks quality up to 11. These ETFs largely disregard valuations in their pursuit of high-quality stocks. Prime examples include Silver-rated Invesco S&P 500 Quality ETF SPHQ and Silver-rated iShares MSCI USA Quality Factor ETF QUAL. Both hold the most profitable large- and mid-cap stocks in the US market.

Their main advantage is diversified and consistent exposure to stocks with stronger fundamentals than the market. Such a strategy has historically outperformed the US market, as proxied by the Russell 1000 Index. They both beat that benchmark by more than 50 basis points annualized over the 10 years through Sept. 30, 2024. That’s not a huge edge, but it’s noteworthy considering most of their actively managed peers in the large-blend category fell short.

The downside is that the outperformance isn’t well understood—no one really knows why higher-quality stocks have performed better historically or why that should continue. And since they both ignore valuations, they’re more susceptible to holding stocks with steep prices. For example, both ETFs had considerable stakes in the market’s most recent darling, Nvidia NVDA, over the past year. The average price multiples of these two ETFs landed among the steepest of any listed in the table below. Profit levels and balance sheets aside, those multiples may not always be justified.

All the ETFs in the table have merit on their own, and they accordingly receive Silver and Gold Medalist Ratings. One is not necessarily better than the other in an absolute sense. All should work well over long holding periods. The strength (or weakness) of their value and quality characteristics will influence their performance in different ways across a full market cycle.

The author or authors do own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar's editorial policies.