Why choose a broadly diversified fund over a strategy that sticks to a few great ideas? The most common answer goes something like this:

Portfolio-level risk depends on both the individual holdings and how those holdings interact. Combining securities whose performance shows little relation to one another (low correlation) can reduce overall portfolio volatility without sacrificing much return. In other words, diversifying stands to improve risk-adjusted performance.

By extension, many investors think of diversification as disaster protection. A stock that abruptly goes to zero would seriously damage a fund that invests in it and just a few others. In a diversified portfolio with hundreds of other companies, that kind of downfall leaves a small dent. This traditional conception of diversification’s benefits is true but incomplete.

The cost of investing in a stock that fails is obvious. The cost of not investing in a stock that succeeds is more inconspicuous, but it can be just as significant. Diversification not only confers “disaster protection,” but also “miracle exposure”—an expanded case that underscores the appeal of investment strategies that cast as wide of a net as they can.

Tails Wag the Market

In The Psychology of Money, author Morgan Housel details how renowned art collector Heinz Berggruen built one of the world’s most valuable art collections by indiscriminately buying in bulk, then waiting for a few emerging standouts to drive gains for his full portfolio. “Perhaps 99% of the works that someone like Berggruen acquired in his life turned out to be of little value,” Housel writes. “But that doesn’t particularly matter if the other 1% turn out to be the work of someone like Picasso. Berggruen could be wrong most of the time and still end up stupendously right.”[1]

Perusing Picasso’s Blue Period is far more romantic than analyzing the utilities sector, but Berggruen’s approach to art collecting translates to investing. Like pieces of art, most stocks are worth very little when all is said and done. Research from J.P. Morgan found that 44% of all companies in the Russell 3000 Index from 1980 through 2020 suffered a price decline of at least 70% from their peak and never recovered.[2] Yet that index climbed nearly 12% per year over that period, turning a $10,000 investment at the beginning of it to almost $900,000 by 2020’s end.

This success owes largely to a select few companies whose meteoric returns compensated for the many more that crumbled. Carve out a narrow portfolio of a select few stocks, and you run the risk of omitting the ones that will drive the lion’s share of overall returns. Putting more lines in the water increases your chances of reeling in a trophy fish.

The last two years offered the latest evidence that index growth normally stems from a handful of standouts, not hundreds of companies pulling their weight. The techy “Magnificent Seven” stocks generated half of the Morningstar US Market Index’s 57% cumulative gain from 2023 to 2024. In other words, 50% of the broad benchmark’s gain traced back to 0.05% of its holdings.

Recall that these firms were not always household names. Nvidia NVDA and Tesla TSLA were just the 36th- and 120th-largest Morningstar US Market Index constituents in November 2018. They grew 3,213% and 1,628% from that point through 2024, rewarding investors whose nets were cast wide enough to catch them early.

Winners Have Been Wide

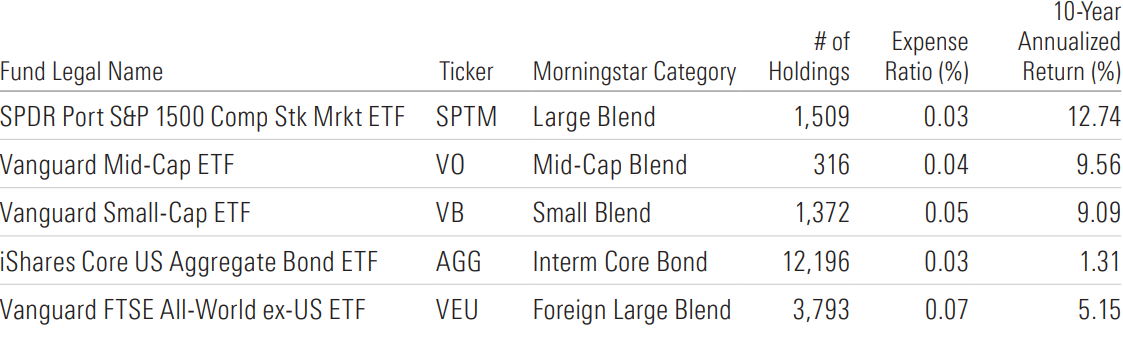

The benefits of a wide scope normally take a long time to come to life. Still, comparing the performance of exchange-traded funds with varying breadth can illustrate whether diversification has paid off in recent years.

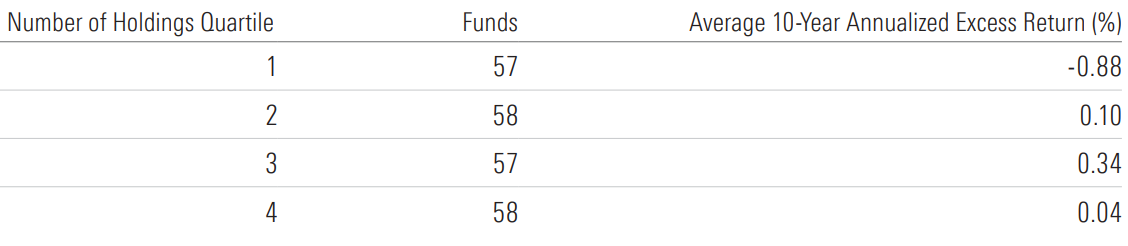

Exhibit 1 includes US equity ETFs that have traded for at least 10 years, sorting them into quartiles based on their average number of holdings over the past decade. Quartile 1 represents the fewest, quartile 4 the most. Those in the leanest quartile posted the worst returns by far. They trailed their category indexes by an average 87 basis points annualized from 2015 through 2024, while those constituting the broader three cohorts each outpaced their benchmarks. Quartile 4 succeeded but didn’t quite excel. That mainly owes to its heavy dose of total-market and small-cap index funds, while Quartile 3 included more large-cap index trackers—the real stars of the past decade.

There was a wide range of outcomes among the choosiest quartile of funds. For instance, Global X Guru ETF GURU targets hedge funds’ best stock ideas, a requirement that only 61 companies met as of Dec. 31, 2014. That did not include Microsoft MSFT (eventually purchased in February 2021), Apple AAPL (November 2021), or Nvidia (May 2023). Adding those highflyers late saddled this fund with an annualized deficit of 6 percentage points versus the Morningstar US Large-Mid Cap Index, its Morningstar Category benchmark. On the other hand, the 50-holding First Trust Rising Dividend Achievers ETF RDVY trounced its respective category index by 4 percentage points annualized.

Opting for broader ETFs reduced the importance of picking the right stock and led to better average results. Funds like Schwab Fundamental US Large Company ETF FNDX, which carries a Silver Morningstar Medalist Rating, entered 2015 with nearly 1,500 holdings and beat the Russell 1000 Value Index by 2.8 percentage points annually over the next decade. Its sprawling portfolio included stocks like Nvidia and Amazon.com AMZN—winning lottery tickets that propelled it ahead of its category benchmark.

It’s important to consider fees when evaluating this performance. More selective funds, which sport a higher active share, tend to charge more. Morningstar found in a 2021 paper that “high-active-share funds failed to justify their fee premium in most categories, as measured by their performance over 12-month rolling periods.” So, in addition to the stand-alone appeal of broadly diversifying with a wide portfolio, funds that do so normally come at a better price point.

What About Multi-Asset Portfolios?

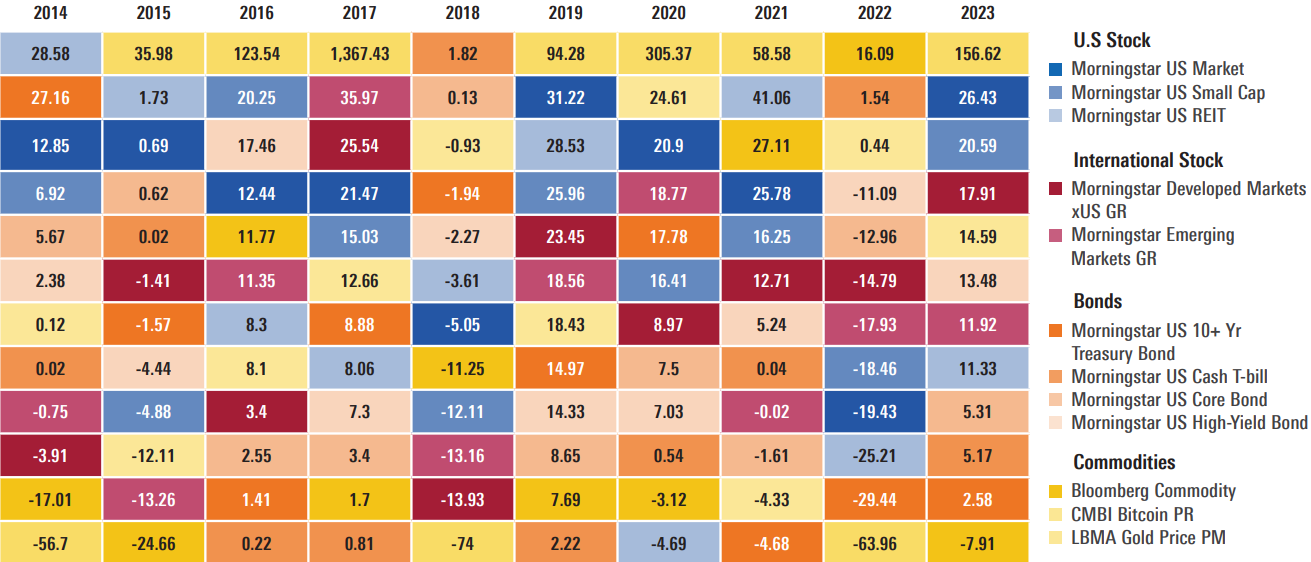

The case for diversifying across traditional asset classes—stocks, bonds, and cash—is one of disaster protection more than miracle exposure. Stocks and bonds have marched similarly lately, but their performance has historically shown low interaction. From 2000 through 2024, the Morningstar US Core Bond Index posted a 0.13 correlation with the Morningstar US Market Index, signifying a relationship that’s tenuous at most. The bond index never gained more than 12.5% in a calendar year over that span; stocks cleared that threshold in 14 of them. Including bonds is about fortifying the floor, not raising the ceiling.

Introducing alternatives can change that calculus a bit. Exhibit 3, lifted from Amy Arnott’s annual Diversification Landscape Report, ranks asset-class performance in each of the past 10 calendar years. International stocks, real estate, and traditional commodities like gold didn’t show lottery-ticket potential, but bitcoin certainly did. That seems to make the case for a small cryptocurrency allocation, but buyer beware. Bitcoin’s 64% drop in 2022 is a fresh reminder that it can go off the rails fast, and investors have historically timed crypto investments poorly.

Building a diversified portfolio is a good idea because it should lead to a smoother ride, but investors should be cautious about big game hunting with unproven asset classes.

In Conclusion

Strategies that invest in a few “best ideas” can be tempting, but identifying market leaders before they take off is a tall task—even for professional portfolio managers. In both fund selection and asset allocation, diversification is a virtue. Not only does it protect the downside and improve risk-adjusted performance, but it also opens the door for the next standout security to walk right in.

[1] Housel, M. 2020. “The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness.” (Hampshire, UK: Harriman House).

[2] Cembalest, M. 2021. “The Agony and the Ecstasy: The Risks and Rewards of a Concentrated Stock Position.” J.P. Morgan Eye on the Market, Special Edition.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar's editorial policies.